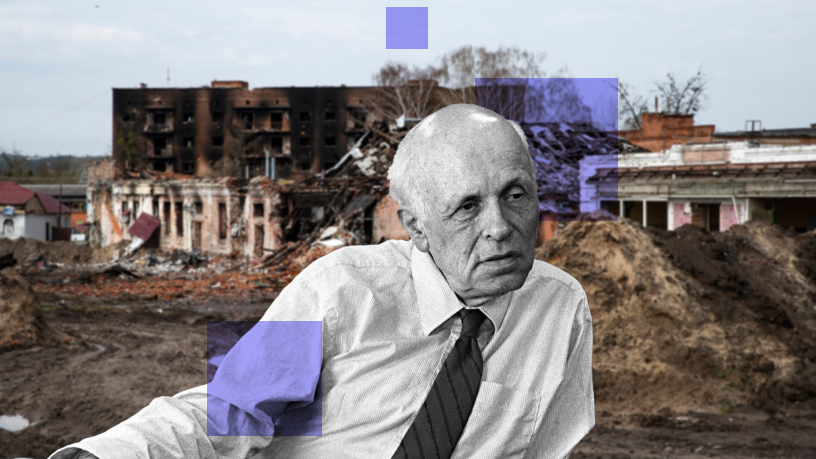

Alexander Kabanov, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

As a Russian-speaking scholar who was born and raised in the USSR and has lived in the United States for more than 30 years, I am concerned about finding harmony between past and recent emigration, each facing problems that extend beyond the post-Soviet theme. The issues of various countries, including Russia, Ukraine, Israel, the United States, and China, are part of the global agenda for humanity’s future, encompassing technological and humanistic challenges that are being revisited today and disturb many of us. The question of the purpose of life for each individual and society, especially for the Russian-speaking and scientific intelligentsia, poses a new “dispute between physicists and lyricists” within the context of the Sakharov paradigm of “Peace, Progress, Human Rights.”

In his Nobel lecture, Andrei Sakharov postulated: “I am convinced that international confidence, mutual understanding, disarmament, and international security are inconceivable without an open society with freedom of information, freedom of conscience, the right to publish, and the right to travel and choose the country in which one wishes to live. I am likewise convinced that freedom of conscience, together with the other civic rights, provides the basis for scientific progress and constitutes a guarantee that scientific advances will not be used to despoil mankind, providing the basis for economic and social progress, which in turn is a political guarantee for the possibility of an effective defense of social rights”.[1]

Today, almost half a century after this speech, nearly every maxim that forms the basis of Sakharov’s beliefs has either been “refuted” or questioned.

We are witnessing two major conflicts: the war in Europe, resulting from Russia’s attack on Ukraine, and the war in the Middle East, following Hamas’s attack on Israel. These conflicts are not merely local or bilateral; they have broader, more general implications. Russia’s aggression against Ukraine aims to provoke a global conflict to weaken NATO and the West as a whole. Similarly, Hamas seeks to destroy Israel with the support of Iran and Hezbollah, making this confrontation far-reaching.

In each of these conflicts, the interests of superpowers such as the United States, China, and Europe are intricately and contradictorily involved. Both conflicts risk escalating into a new world war. Amid these terrible events, there has been a sharp deterioration in international relations and security across almost all fronts.

Trust and mutual understanding between countries and peoples are at one of the lowest levels since the end of World War II. Unlike the Cold War conflicts, the current situation lacks the agreements that once existed between the countries of the “collective West” on many key issues. Nationalist and isolationist tendencies are on the rise globally, and political populism and opportunism are flourishing.

After the Hamas attack on Israel, during which more than a thousand people were publicly raped, mutilated, and killed “on camera,” a wave of anti-Semitism swept around the world and has not subsided. It is disheartening that in leading universities of Western countries, notably in the United States, mass actions are taking place under the guise of freedom of speech and the need to protect Palestinians from the actions of the “Zionist” government, calling for the destruction of Israel.

Confidence in the United States as the leader of the “free world” has been undermined due to its relative decline in economic influence and intense internal political confrontation. China, as a world power, does not yet play the significant foreign policy role that the Soviet Union once did. Meanwhile, a revanchist Russia still possesses a colossal nuclear arsenal and openly threatens to use nuclear weapons in its confrontation with Ukraine and NATO. The weakening of Russia as a world power and its drastic degradation in various aspects increase the risk of this threat becoming a reality, posing a great danger to humanity.

The values of “openness of society, freedom of information, freedom of belief, publicity, freedom of travel, and choice of country of residence,” which seemed indisputable for decades, have eroded not only in totalitarian and authoritarian societies but also in countries of “liberal” democracy. During the coronavirus pandemic, populations in these countries faced widespread restrictions. This period highlighted the low effectiveness of national and international health institutions and humanity’s poor readiness to develop a collective response to a global threat.

On several issues less noticeable to the general public, there has been a retreat from the principles of international cooperation and restrictions on personal and corporate freedoms. A notable example for scientists is the “fight against foreign influence in science” in the United States, also known as the “China Initiative.” Despite public rejection of this initiative, federal restrictions on scientific cooperation with several countries continue to grow.

Science and culture are no longer the unifying spheres of human activity they once were during the USSR era. Unlike the 1960s and 1980s, when the USSR Academy of Sciences held considerable authority both domestically and internationally, today’s Russian Academy of Sciences has been reduced to a “club of interests” and is entirely subjected to Kremlin pressure.

Russian aggression in Ukraine has greatly exacerbated the demarcation processes between countries, calling into question the fundamental principles of scientific and publication activities. Today, it is natural, though unfortunate, that Ukrainian and some European scientists demand and often seek the termination of scientific contacts with Russians, their exclusion from international scientific organizations, and their non-admission to scientific conferences.

In parallel, and quite symmetrically, a significant number of European and other scientists are pushing for a boycott of Israelis, including bans on their publications, non-invitations to scientific conferences, and refusals to cite their scientific papers. Regardless of the motivation and moral justice or fallacy in each case, such calls harm science and exacerbate international divisions.

Unfortunately, the examples of cancel culture, radicalization of public discourse, and excessive state interference in science, education, and culture can go on for a long time. It is difficult to imagine what Andrei Sakharov would have said if he were alive today.

However, it seems to me that the moral and ethical message of his words remains true in the modern world. One can argue about what means are permissible to achieve peace, what the essence and direction of “progress” are, what “human rights” entail, and where the limits of these rights lie. However, one cannot but agree with Sakharov’s maxim: “Peace, progress, human rights – these three goals are inextricably linked; it is impossible to achieve any of them by neglecting the others.”

The question arises: what exactly can and should we, living today, do to achieve these goals? Is our voice as weak in this chaotic and multi-voiced world as it seems at this moment? What is the role and weight of our “intelligentsia” statements in the face of extremism, terrorism, war, and mutual hatred?

In this context, I want to revisit the well-known “dispute between physicists and lyricists” from the USSR in the 1950s and 1960s. Essentially, this was a conversation about the necessity, contradiction, and mutual complementarity of pragmatism and artistry in social life. I believe that in modern conditions, what we need most is love – for ourselves, our neighbors, nature, art, and talent. Love is the starting point of cultural and spiritual resistance to evil and the restoration of humanity. This is something that all participants in the modern world should consider. However, I especially want to address my compatriots, the people of the aggressor nation, as well as all Russian-speaking individuals and bearers of Russian culture outside the Russian Federation.

Today, many decent, educated, and talented Russians, including the cream of Russian culture, art, and journalism, have found themselves in forced emigration. Like 100 years ago, the “Russian world” is divided into those who remained and those who left the country. This is a colossal tragedy for both Russia and those who have left. At the same time, the newly arrived “lyricists” can unite with “physicists” (scientists, engineers, professionals, entrepreneurs) who left after the collapse of the Soviet Union and have long settled in their new countries. For the development of Russian thought and creativity on the international stage, this is an opportunity that can lead to new achievements and integration into the global discourse. This opportunity cannot be ignored in the current circumstances.

As for the domestic Russian agenda, it is a mistake to believe that the diaspora, divorced from Russian reality, cannot exert any influence on the metropolis. Foreign Russian thought and culture, which developed in the last century, played a significant role in the country’s return to universal human values during Gorbachev’s “perestroika.”

Despite the Russian government’s efforts to isolate its citizens, this task is doomed to failure, both technologically and, more importantly, historically. For example, the T-Invariant media platform, created by scientific journalists and recognized in Russia as a foreign agent, remains blocked by Roskomnadzor but still retains half of its audience within Russia. Today, unlike in the past century, Russian emigration is much more “connected” thanks to modern means of communication. This connectivity strengthens the potential for interaction within the diaspora itself and facilitates the interpenetration of ideas within Russia. I have no doubt that the Russian-speaking diaspora will play an important role in shaping the future of Russia, even from outside its borders.

I want to emphasize the role of scientists as a unifying factor in our emigration. Scientists around the world are united by the very essence of the scientific process, perhaps more than any other profession. This fully applies to the Russian-speaking scientific diaspora, where cultural and linguistic commonality serves as an additional factor for unification, alongside mutual professional interest, respect, and understanding. The scientific diaspora should, by its example, help the new “Russian diaspora” overcome the disagreements and conflicts that we unfortunately observe among the Russian emigration.

The question inevitably arises: what should scientists in the Russian-speaking diaspora do here and now? I believe it is necessary to focus on concrete and urgent tasks, with assistance to scientists affected by the war being a priority. This includes Ukrainians, Russians, and Belarusians. Today, we need to create effective mechanisms for the cultural and professional adaptation and integration of scientists and students who were forced to leave their countries due to the war.

While it is necessary to be active and visible in the Russian-speaking public space, we must not confine ourselves to it. We need to participate in national and international discourses to overcome misunderstandings and disagreements in our countries. A recent example of such action is a letter initiated by Russian-speaking scientists, signed by 40 Nobel laureates, in support of Ukraine and the democratic opposition in Russia. This letter was joined by nearly a thousand scientists from all over the world.[2]

Without exaggerating the influence of Russian-speaking scientists and scientists as a whole on the fate of humanity, we must recognize our responsibility today, just as we did in the time of Andrei Sakharov. We have much to do, both individually and collectively. Perhaps the most challenging task now is to stop squinting and open our eyes. We need to look ahead and work together to develop a vision for the future. This is a difficult but necessary task, not only for Russians but for all people. The goal of such individual and collective action should be the return of humanity to Sakharov’s principles of “Peace, Progress, and Human Rights.

Text: Aleksandr Kabanov, October 11, 2024. First published in Russian: Kabanov, A. (2024). Глобальные вызовы и поиск гармонии в контексте Сахаровской парадигмы. 7 Iskusstv, 10. Retrieved from https://7i.7iskusstv.com/y2024/nomer10/akabanov/. Author’s translation with editing using Bing Copilot.

[1] Sakharov, A. (1975). Peace, Progress, Human Rights. Nobel Lecture. Retrieved from https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/1975/sakharov/lecture/

[2] No tolerance for Putin’s regime: A call from the world’s scientists. Retrieved from: https://www.t-invariant.org/2024/03/nikakoj-terpimosti-k-rezhimu-putina-br-prizyv-uchenyh-mira/