Leading academic institutions like MIPT (Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology) and ITMO University have emerged as key drivers of Russia’s military-technological ambitions. These universities now host the intellectual hubs behind “drone swarm” systems—a cutting-edge frontier in military unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). This report by T-invariant examines the most striking examples of how Russia’s education system is being militarized, detailing state-led efforts to recruit young specialists, university students, and even schoolchildren into drone development programs.

“Engineers of the Future for New Technologies”

Since January 1, 2024, Russia has implemented the national project “Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS)”. While officially focused on civilian applications, it concurrently funds military enterprises. The initiative includes the “Workforce for UAS” program, which integrates drone operation training across all educational levels.

The “Prosveshchenie” publishing house has released a school textbook on drones, technical colleges have adopted state standards for UAV operation, and retraining programs now target adults and seniors. Prestigious universities like Moscow’s MIPT and St. Petersburg’s ITMO have launched dedicated bachelor’s and master’s programs in drone technologies. T-invariant investigates who is being trained, in what numbers, and interviews students about their experiences.

“Field irrigation, search-and-rescue operations, and research in hazardous environments,” lists an MIPT spokesperson when describing the career prospects for graduates of its new “Unmanned Aircraft Systems” bachelor’s program. The inaugural cohort enrolled in summer 2024 saw fierce competition – 27 applicants per seat, with average entrance exam scores exceeding 95%.

Yet by MIPT’s standards, the intake was modest. The state allocated 28 state-funded slots across three specializations: aviation, radar systems, and drones. An additional 18 students enrolled through quotas and targeted recruitment, while eight pay 500,000 rubles annually. A program student revealed to T-invariant that only 13 trainees comprise the current drone specialization cohort.

MIPT’s drone program operates under the “Advanced Engineering School (AES)” framework – one of 50 such institutions nationwide training ~6,000 students. The initiative traces back to fall 2021 when the Education Ministry announced plans to modernize engineering education, with AES applications opening after spring 2022.

What Are Advanced Engineering Schools (AES)?

Tomsk, Voronezh, and Omsk Technical Universities state that their Advanced Engineering Schools (AES) are “training the engineers of the future to develop cutting-edge technologies.” Among the 22 focus areas for this “advanced” education are artificial intelligence, biotechnology, nuclear energy, as well as more traditional fields like oil and gas engineering and shipbuilding. The key feature of AES programs is their practice-oriented approach. From the very first year, students collaborate with specialized companies that have partnered with the schools, ensuring hands-on experience in real-world industry projects.

The drone program at the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology (MIPT) has several partners: the defense conglomerate “Almaz-Antey”, the “Ural Plant of Civil Aviation”, the “Kronstadt” design bureau, and the company “Geoscan”. All of them are linked to the war in Ukraine. “Kronstadt” developed and manufactures the “Orion” reconnaissance and strike drone, which, as stated on the company’s official website, “has proven itself in the Special Military Operation zone.” Despite its “civilian” name, the “Ural Plan” has long held contracts with the Russian Defense Ministry, and its “Forpost” drone is among those used on the frontlines. Employees of “Almaz-Antey” travel to the combat zone to maintain air defense systems, while the military actively employs the company’s products in combat operations. “Geoscan” is the only one concealing its involvement in the war, but the Prime Minister of Bashkortostan revealed that a subsidiary of the company supplies equipment to the front. Following this, “Geoscan” was placed under Ukrainian sanctions, while the other three companies are already under U.S. sanctions.

The hours allocated for project work and practical disciplines increase with each academic year. Nevertheless, most of the students’ time is devoted to fundamental subjects: physics, mathematics, and programming. In specialized courses, students are expected to learn about drone design, the aerodynamic and impact-resistant properties of materials, propulsion systems, communication systems for control and navigation, machine vision, and programming for swarm operations (the so-called “drone swarm” technology, which has also drawn significant interest from the Russian military). Overall, the curriculum covers all aspects of drone engineering. “We’ll have specializations in structural integrity, avionics, and payload systems so that collectively, we cover every stage of UAV design and development,” a student on the program, Timur (name changed), told T-invariant.

Why Students Enroll in Drone Engineering – and Whether They Enjoy It

“I still don’t know what I want to do, and more of my friends ended up in Dolgoprudny,” says Alexey (name changed), another first-year student at MIPT. He initially considered the drone program “because, at first glance, it seemed to balance physics, math, programming, and engineering equally.” But he ultimately chose geospatial technologies instead. The deciding factor was the drone program’s campus location in Zhukovsky, far from MIPT’s main facilities.

Timur, who enrolled in the unmanned aerial systems (UAS) program, says he originally planned to study software engineering but was determined to attend MIPT above all. “I enjoy combining code with hardware, and when I learned that this intersection is a core focus at MIPT, the choice became obvious. Plus, it’s a highly in-demand and promising field right now,” he explains.

Though hands-on engineering workshops and industry collaborations won’t begin until their second semester, Timur notes that his cohort was already invited to tour “Kotlin-Novator”, a partner company producing avionics for civilian and military aircraft, as well as drones like the “Veter”, “Buran”, and “Y-89”— many of which are supplied to the frontlines. According to HeadHunter, entry-level salaries at “Kotlin-Novator” range from 70,000 to 130,000 rubles, depending on specialization.

“The coursework is quite demanding, but also fascinating. I haven’t encountered a single bad instructor—they all go out of their way to explain concepts clearly and never refuse help. […] The students here are incredibly supportive, from upperclassmen to peers. Everyone’s willing to clarify tough topics, assist with assignments, or just offer encouragement,” Timur says, reflecting on his first months in the UAS program. When asked about career aspirations, he adds: “Some want defense sector jobs, others prefer civilian roles, and some don’t care either way. Personally, I’d lean toward civilian applications, but I wouldn’t rule out defense work either.”

In MIPT group chats, applicants to non-drone-related programs ask whether they’ll get to “have some fun with drone swarms” during their studies. University staff emphasize that “all basic departments are invested in UAV development.”

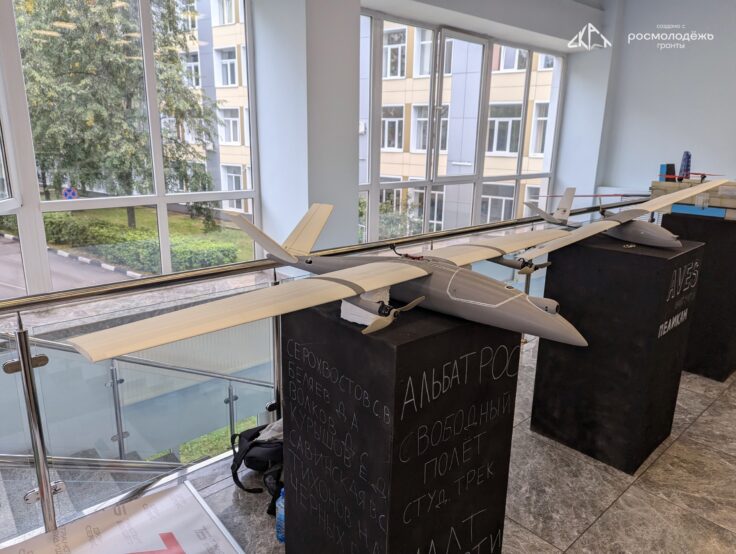

MIPT also hosts the student design bureau “Aerokitties”, formed back in 2018. The team competes in drone engineering contests, organizes its own events, attends federal UAV forums, and runs career guidance workshops for school students. Together with pupils and undergraduates, “Aerokotties” 3D-prints drone components, designs flight data processing boards, and conducts test launches.

One of MIPT’s recent graduates, Alexander Makhnev, co-founded the major design bureau “Stratim” after completing his master’s degree in 2017. In recent years, “Stratim” has been actively supplying combat drones to the frontlines. In August 2023, the company unveiled its first domestically produced UAVs at the “Dronitsa-2023” exhibition (covered later in this article), including the “Shchegol”, “Krasava”, and “Rusak” models, among others. The investigative outlet “Vazhnye Istorii” (iStories) published a high-profile exposé on this design bureau.

From Drone Swarms to the “Ushkuynik”

Since the start of the war, specialized higher education programs exclusively focused on unmanned systems have been launched at three other leading universities. Unlike MIPT’s bachelor’s program, these are more narrowly tailored to specific aspects of drone technology.

At the Moscow Aviation Institute (MAI), two new bachelor’s programs were introduced: “Control Systems for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles” and “Intelligent Navigation and Data Measurement Systems for Drones.” These are part of the “Institute of Robotics and Intelligent Systems” and emphasize programming for autonomous navigation, target acquisition, and precision strike capabilities. The programs collaborate with state corporations like “Rosatom” and “Roscosmos”, as well as both civilian and defense industry partners.

MAI also offers four specialized master’s tracks in UAV technology, including drone design, certification, and payload data processing—a skill set applicable to both logistics and military operations. Another program, “Modeling and Optimization in Unmanned Aerial Systems,” is run by the Advanced Engineering School and has an even more pronounced “front line” focus than MIPT’s undergraduate curriculum. Alongside core engineering subjects, it includes courses like “Professional Development and Industry Leadership,” “Creative Research and Inventive Methods,” and “Technological Entrepreneurship.” One might infer that these prepare graduates for negotiations with government officials and state grant committees.

On January 31 of this year, First Deputy Prime Minister Denis Manturov held a meeting at the “military Skolkovo” — the Era technopolis in Anapa — to discuss “the impact of artificial intelligence (AI) on enhancing combat effectiveness of units in the warzone, increasing offensive capabilities of weapons, equipment, and control systems.”

“Most existing and planned developments have dual-use potential. Our task is to leverage them for solving applied military challenges,” Manturov emphasized.

Then on February 5, Russia launched a “dual-use technologies accelerator,” with participating startups and academic groups from universities.

In 2023, St. Petersburg’s ITMO University launched a master’s program in “Unmanned Systems Security”, with the stated goal of “making drone transportation safe and accelerating its integration into everyday life.” The program is significantly larger than counterparts at MIPT and MAI, offering nearly 200 state-funded spots. While focusing primarily on programming and AI, it also emphasizes entrepreneurial skills, creative technologies, and soft skills like time management, negotiation, and even storytelling.

Among its promotional materials is an interview with ITMO researcher Andrei Boyko about drone swarms — a topic he also lectured on at the 2024 “Dronitsa” festival. Notably, “Dronitsa” is organized by the “Coordination Center for Novorossiya Support”, which frames Russia’s war against Ukraine as a “new campaign for Kyiv.” ITMO also partners with “Geoscan”, offering students factory tours and internships.

“Geoscan was best known pre-war for its drone light shows, coordinating over 2,000 units via centralized control,” an AI expert told T-invariant. “Now, drone swarms represent the most promising military application—whether for attack or defense. ITMO has likely become the neural center for AI models managing these swarms, given its technical caliber.”

How Drone Swarms Operate

In drone light shows, the primary difficulty lies in preventing mid-air collisions. In military applications, however, the critical challenge is ensuring the swarm maintains cohesion despite electronic warfare (EW) measures and active enemy countermeasures. Several solutions exist. The simplest approach mirrors show drones: a centralized control system, typically operated by a single person, directs the swarm rather than individual units. Here, drones coordinate their positions and follow commands from the hub. Yet this method inherits the same EW vulnerabilities—jamming and spoofing—as single-drone operations, which we have previously discussed.

More advanced solutions leverage AI models to enable autonomous swarm control. One variant relies on a central server system, where one or several “leader” drones act as relays for the rest. However, this too remains susceptible to EW disruption. Alternatively, drones could coordinate mission execution through local interactions—observing and mimicking nearby units, much like birds in a flock. While no operational systems of this kind are currently known, digital prototypes are under active development.

Stopping such a swarm is extremely difficult—nearly impossible without another swarm. To date, no recorded aerial battles between autonomous drone swarms have occurred. However, controlling such swarms requires highly advanced AI models capable of real-time decision-making.

ITMO University maintains close ties with military-oriented drone developers. A key figure in this sphere is political strategist Alexey Chadayev, who after 2022 spearheaded a “people’s drone production” initiative—crowdfunding grassroots manufacturing and lobbying for “garage engineers” within government circles. Chadayev named the project “Ushkuynik” (after 14th–15th century Novgorodian and Pomor “pirates”), with drones dubbed “Osoyed” (“Honey Buzzard”) and “Knyaz Vandal Novgorodsky” (“Prince Vandal of Novgorod”).

Meanwhile, Southern Federal University (SFU) offers a master’s program in “Secure Unmanned Automated Systems”. Though SFU is based in Rostov-on-Don, its drone specialization is taught at a branch campus in Taganrog for 20 students. The curriculum parallels St. Petersburg’s programs—focusing on programming and a substantial “personal resource management” module—but adds specialized training in physical sensors. These enable drones to generate thermal maps or detect hostile UAVs. “The state actively supports unmanned systems development,” the university emphasizes. Partners include “Geoscan”, Taganrog firms “Integra” and “Computer Systems Design Bureau”—the latter holding multimillion-ruble contracts with “Burevestnik”, a state artillery and mortar research institute.

Notably, Taganrog’s program avoids framing itself as defense-centric. For instance, SFU’s Institute of Computer Technologies and Information Security (ICTIB), which hosts the drone program, organized the “Cyber Garden Char” hackathon in June 2024. Sponsored by “Rosmolodyozh” (Russia’s youth agency), the event adopted the hashtag *#PilotingUnderPalms*.

Beyond education, institutions like MIPT, MAI, ITMO, and SFU conduct state-funded drone research. T-invariant uncovered documents detailing a 2024–26 R&D competition for unmanned systems, with a total budget nearing five billion rubles.

Overview of State-Funded and Tuition-Based UAV Program Seats in 2024:

In 2024, Russian universities offered a combined 848 state-funded (free) spots and 100 tuition-based spots*** across bachelor’s and master’s programs specializing in unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). Below is the breakdown by institution:

Bachelor’s Programs

– MIPT: 13 total seats*

– MAI: ~57 state-funded + ~5 tuition-based**

Master’s Programs

– MAI: ~67 state-funded + ~16 tuition-based**

– ITMO University: 34 state-funded + 10 tuition-based + 7 sponsored (corporate/government-funded)

– SFU (Southern Federal University, Taganrog branch): 18 state-funded + 2 tuition-based

*institutional data provided by *T-invariant*

**MAI’s figures were calculated by proportionally distributing seats across multiple UAV-related programs under a single admissions code.

***Sourced from RBC.

Government Grants for UAV Research: Universities Leading the Race

The Russian government has allocated grants to universities for drone-related research, with MIPT (Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology) securing the most—five out of thirty. Close behind is MAI (Moscow Aviation Institute) with four grants, followed by SFU (Southern Federal University) and ITMO University, each receiving two.

Other top recipients include: Innopolis University (Tatarstan), 3 grants and TUSUR (Tomsk) & Zhukovsky Central Aerohydrodynamics Institute (TsAGI, Moscow Oblast), 2 grants each. Additionally, nine other universities and research institutes from Moscow, Ryazan, Cheboksary (Chuvashia), Samara, and St. Petersburg were awarded one grant each.

The largest grant in this competition amounted to 311 million rubles for a three-year period, awarded to Innopolis (Tatarstan). The smallest grant, worth seven million rubles for developing satellite navigation systems for drones, went to the MIPT. The minimum grant size is comparable to funding from targeted competitions held by the Russian Science Foundation, while the maximum mirrors the budgets of megagrants—a highly selective open competition that awards only a few dozen such grants annually.

This suggests that drone-related research now offers universities a significant opportunity to secure additional state funding. For scientists and research managers, this could serve as a strong incentive to focus on this field, especially given widespread concerns about underfunding in education and scientific research. At the very least, students gain exposure to the work of specialized laboratories; at best, they become directly involved in government-contracted projects beyond just corporate partnerships. For instance:

– SFU is developing flight control and navigation systems;

– ITMO University is programming drone swarms and testing object recognition and “movement prediction” systems;

– MAI is working on control systems, navigation, large-scale UAV design, and holistic drone engineering technologies;

– MIPT is focusing on engines, computer vision, and—as noted earlier—navigation, including satellite-based solutions.

The scope of the grants spans the entire drone production pipeline—from component manufacturing to programming, control systems, and market standardization. Clearly, the state is investing in the drone industry by funding both research and educational programs at leading universities. At the same time, industry associations with ties to the authorities have, at the very least, criticized the grant competition.

“Two years to develop and industrialize an engine capable of competing with foreign counterparts is a critically short timeframe. […] Sectors in need of support will keep relabeling products to meet localization quotas, passing off foreign-made goods as domestic,” argue experts from the AeroNext Association. “It’s a risk-free tactic for subsidy recipients, but ultimately futile for the market,” they conclude. The program, they warn, risks becoming a “Klondike for foreign companies,” with Russian researchers and manufacturers continuing to rely on imported components.

Drone-related initiatives aren’t limited to MIPT, MAI, ITMO, and SFU. According to the aggregator Vuzopedia, over 40 higher education programs in Russia now specialize in UAV technologies.

UAVs and AI at Moscow State University

“Russia has adopted a more pragmatic approach to AI development, driven by the country’s specific challenges and priorities—such as UAVs and the oil and gas sector,” said Katerina Tikhonova, head of MSU’s Artificial Intelligence Institute and daughter of Vladimir Putin, during a recent conference. Following the outbreak of the war, her institute at Moscow State University (MSU) acquired a powerful new MSU-270 supercomputer, exclusively dedicated to AI tasks. The supercomputer was assembled using gray-market imports, while Tikhonova’s institute focuses on dual-use technologies—read more in the investigation by T-invariant.

Another Key Player in Drone Development: The National Technology Initiative

The organization overseeing both the grant competition and drone-related education has repeatedly raised doubts about its effectiveness. This is the National Technology Initiative (NTI), which since 2015 has been responsible for analyzing and developing innovative markets deemed “critical for national security and citizens’ quality of life.” These include smart home technologies, the Internet of Things, cybersecurity, as well as aviation, automotive, and maritime sectors. However, a 2023 report by Russia’s Audit Chamber revealed that NTI had missed deadlines for more than half of its state-funded projects.

Despite this, NTI remains an influential entity—likely due in part to its ties to Andrey Belousov, the current Defense Minister, who previously supervised the organization and spearheaded a national drone development program. Now, Belousov is leading the creation of a dedicated unmanned warfare branch in the Russian military, while NTI Director Dmitry Peskov (namesake of the presidential press secretary) delivers lectures on building a “heavenly civilization of drones.”

Though some of Peskov’s speeches veer into science-fiction rhetoric, NTI itself has long come down to earth. Many grant-winning universities host NTI Competence Centers—mega-labs aligned with their funded research: ITMO focuses on machine learning for drone swarms and object recognition; TUSUR (Tomsk) specializes in data encryption, the focus of its drone grant; MIPT works on AI and batteries, tying into navigation and engine development.

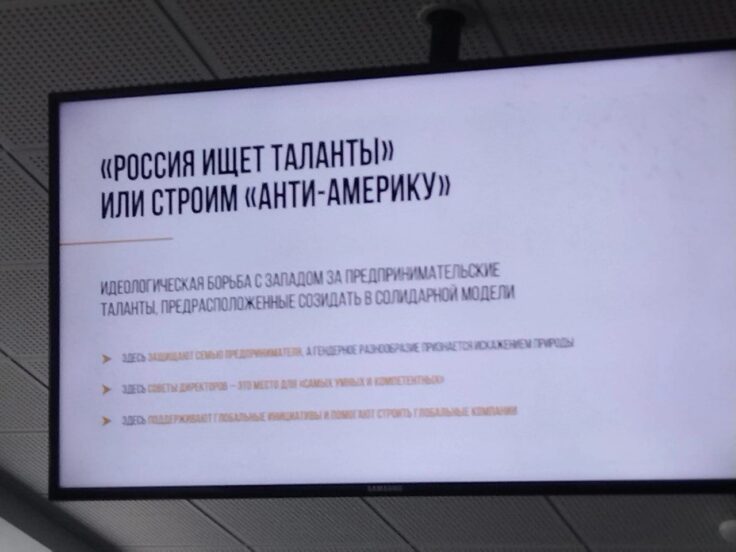

Students and faculty from drone programs also attended NTI’s flagship Archipelago Forum, which drew 4,000 participants to Sakhalin Island. Events included drone races, exhibitions of Russian UAVs by key manufacturers, discussions on “technological sovereignty,” and even a street-art performance where Misha Most painted graffiti using drones.

Controversially, slides from the forum went viral, proclaiming: “Russia seeks talent and builds an Anti-America.” Among the stated advantages in the “ideological battle for entrepreneurial talent” were “family values” and the rejection of “gender diversity as a distortion of nature.”

Not Just Drones

On Chekist Day 2023 (December 20), Russia’s National Technology Initiative (NTI) unveiled “Comrade Major” (*Tovarishch Mayor*)—a neural network designed to deanonymize Telegram channels. The system is currently undergoing internal testing at its developer, T.Hunter, as confirmed by NTI’s press service.

Beyond Universities

The National Technology Initiative (NTI) has expanded its reach beyond higher education, launching retraining programs to meet the growing demand for drone specialists.

“In 2024, we received over 13,000 applications for training. To date, more than 7,500 individuals have been enrolled in programs offered by our certified providers,” announced Alexey Stepanov from University 2035 during an NTI conference focused on workforce development for the drone industry. “Providers” refer to a mix of universities and private organizations that have been certified and funded by NTI to train future drone operators (“dronovod”—a colloquial term blending “drone” and “driver”).

NTI is offering generous compensation packages—particularly by regional salary standards—to attract drone pilot instructors. Below is an excerpt from their job posting:

Instructors participating in FPV drone pilot and instructor training programs will receive additional financial support from the National Technology Initiative (NTI).

Terms for instructors delivering the programs include:

– A payment of 90,000 RUB per group (10 trainees);

– A 72-hour training course per group;

– Equipment, curriculum, and methodological support provided if required.

This generosity is no coincidence. Russian authorities have repeatedly stated that due to the “new geopolitical reality,” the country will need “1 million drone operators by 2030.” In September 2023, the aforementioned national UAV initiative—referenced earlier in the text—was officially launched.

The Russian government is expanding drone education into schools. According to calculations by DOXA, the state has allocated 540 million rubles for purchasing drones in schools and extracurricular centers. Meanwhile, the Ministry of Education has earmarked a staggering 8.4 billion rubles for UAVs in 2024 alone.

Starting this academic year, many schools will incorporate drone assembly into shop classes, introducing students to UAV technology early. Additionally, Russian vocational colleges will begin mass training programs for future drone operators, as announced by Education Minister Sergey Kravtsov.

A College That Brings Death

The most striking example of a drone assembly training program is the “Alabuga-Polytech” college in Tatarstan, located within the Alabuga special economic zone (SEZ). According to an investigation by the independent regional outlet “Protocol”, the facility produces Iranian-made “Shahed” kamikaze drones. Disturbingly, the second part of the report reveals that minors are now involved in their assembly—under conditions that blatantly violate Russian labor laws.

The investigation contains harrowing details suggesting fascist tendencies among the college’s administration and the SEZ’s leadership. When confronted with these allegations, the college’s response was emblematic of the times: their official Telegram channel released nine videos in which teenagers, visibly subdued, explain that assembling drones is their way of “contributing to the cause” during what they call a “difficult historical moment” for Russia. The young workers—some as young as 16 or 17—openly admit to working 12 or more hours a day, despite this being illegal under Russian law.

Reports of student suicides have repeatedly surfaced in the media, with some unable to endure the brutal conditions of this closed-off institution.

Three years of war have shown that the authorities no longer need aggressive slogans to recruit schoolchildren, students, and young professionals. Instead, they employ subtle nudges—flooding the youth with funding and opportunities.

Military drones are no longer assembled solely in garages as part of a “people’s defense industry” or in vocational colleges operating outside Russian labor laws. The path to working for the front can look far more presentable: drone races, hackathons, art projects, soft skills training, coding courses—until suddenly, you’re assembling kamikaze drones from Chinese components in a university lab.