In January, it became known that bioRxiv—a vital tool for researchers in the natural sciences—had become inaccessible in Russia. Investigating this situation, T-invariant sought to determine how frequently and for what purposes Russian scientists and educators rely on VPNs in their work, as well as how YouTube’s throttling has impacted their research and outreach efforts.

The Preprint Problem

Publishing a scientific article is a crucial step for every researcher. Until recently, journal publication was the only formal way to share findings with peers. However, getting a paper into a reputable journal requires more than just conducting research, analyzing data, and drawing conclusions—it involves a lengthy review process. This is why, alongside traditional journal submissions, scientists increasingly turn to preprints.

Today, there is a classic “big three” of preprint servers:

arXiv — for exact sciences (physics, mathematics, computer science);

bioRxiv — for the natural sciences (biology, biochemistry, ecology);

medRxiv — for medical research.

None of these repositories peer-review submissions, but they do perform basic screening, including safety checks, automated plagiarism detection, and topic relevance assessment. More importantly, authors receive rapid feedback from colleagues—ranging from verification and critiques to full peer reviews.

In November 2024, bioRxiv became inaccessible within Russia. Scientists were forced to rely on VPNs (Virtual Private Networks) – technology that establishes encrypted connections routed through third-party servers, masking users’ actual locations and network origins.

“Recently, I saw a rhetorical question: Why even have the internet if YouTube isn’t available? For biologists, bioRxiv is like YouTube for the average internet user,” explains one anonymous researcher, underscoring the severity of the situation. “Modern biology increasingly revolves around data analysis. It’s now standard practice to publish raw data and computational code alongside findings—this enables independent verification. If you’ve sequenced a new coronavirus gene, waiting for formal publication is pointless. The real value lies in the genetic sequence itself, which preprint platforms release immediately, allowing global peers to validate results faster than any journal’s peer-review process.”

Most of the biologists and natural scientists we spoke to actively rely on bioRxiv (though some still prefer waiting for formal journal publications). All agreed that using VPNs is nerve-wracking, slow, and labor-intensive—connections frequently drop, and service is unreliable. Interestingly, many suspect Roskomnadzor (Russia’s telecommunications regulator) is behind the blockage. Some theorize bioRxiv was accidentally caught in a broader ban targeting unrelated sites.

We sent official inquiries to both Roskomnadzor and bioRxiv regarding the access restrictions. As expected, Roskomnadzor had not responded by our publication deadline. However, John Inglis, co-founder and lead researcher of bioRxiv and medRxiv, explained in his reply to T-invariant that the platform had been compelled to restrict access from Russian IP addresses due to a sharp increase in cyberattack attempts originating from these regions. Several days later, he sent a follow-up message stating that their technical team had successfully mitigated the issue and refined the blocking measures. Fortunately, by the time this article was published, bioRxiv had been restored for Russian users.

Tor help us

bioRxiv is far from the only website that Russian scientists now need a VPN to access. Yet, we also encountered researchers who avoid VPNs altogether—particularly in fields like nuclear physics and bioinformatics.

“I don’t use a VPN—I use Tor,” one explained, referring to the censorship-circumventing browser. “VPNs get blocked too often; most options are either ineffective or expensive. But honestly, I rarely even need it. I watch lectures on YouTube, though lately, many are mirrored on VK. Some sites have geo-blocked Russia, but mirrors are popping up more often. The only things I truly need Tor (or a VPN) for are free book databases.”

Most of our interviewees argue that working without a VPN is virtually impossible. Many cited specialized databases crucial to their fields as examples. A geneticist from Novosibirsk’s Akademgorodok, for instance, admitted relying on a VPN to access The Jackson Laboratory’s mouse genome database.

Scientists also noted that many research groups they follow are active on Twitter (X) or Facebook, making VPNs essential for staying updated and communicating with peers. Even a philologist specializing in Russian language studies confessed to feeling uneasy without one.

“As a Russicist, I rarely need a VPN for research,” she explained. “But it’s infuriating when you can’t access a random website. You feel trapped behind a digital Berlin Wall.”

Some struggled to articulate why they needed VPNs at work—they simply left them running permanently. Others wished they could do the same but found persistent VPN use created complications.

“Lately, Russia has blocked countless resources: social networks, news outlets, and even YouTube in an undeclared (so far) crackdown,” wrote one respondent. “VPNs bridge the gap. Physically in Russia, you’re virtually browsing from the Netherlands or the U.S.—the free world! Installing a VPN is easy, but the problems start after. Connections to unblocked sites slow to a crawl. Many domestic platforms like banking or Gosuslugi (state services) fail entirely. Even some critical foreign research tools glitch—like Mind the Graph, my budget-friendly alternative to BioRender for scientific illustrations, which periodically crashes under VPN. Cybersecurity systems flag proxy traffic as suspicious. Worse, Roskomnadzor aggressively blacklists circumvention tools, causing erratic performance or sudden disconnections. You never know if a resource will load.”

Educators, too, depend on VPNs for teaching.

“I use a VPN daily to prepare lessons,” said a physics and math schoolteacher. “Some sites block Russian IPs. Finding materials—handouts, problem sets, videos—means constantly toggling the VPN. Educational content on YouTube used to stream directly in class; now I have to download it first.”

An even more complicated situation was described by an instructor who trains science journalists, editors, and communicators in content creation. Our interviewee employs the flipped classroom method: her students study theory before class, then work on practical assignments during seminars and workshops. But even accessing the long-form materials sent for preparation has become a challenge for her students:

“One student opens a file with their provider—the video works, but the interactive element doesn’t, and the text is inaccessible. Another student, using a different provider, encounters a different combination of what loads and what doesn’t. I’ve had to convert all theoretical materials into plain .txt files just to ensure they open consistently on every computer. Twice a year, I have to ‘reimagine’ my entire course—removing services, links, and programs that have become unavailable, finding alternatives, and reuploading videos. I can’t exactly tell my students within university walls to ‘just download a VPN’ to access the tools and sites I recommend. Eventually, I began maintaining a spreadsheet tracking services that had become inaccessible in Russia for various reasons: some were blocked by their own developers, others by Russian authorities, and some remained technically accessible but unusable due to payment restrictions. By July, my list had 90 entries. Now it’s over 150. For my university course, I host videos on Kinescope, a paid storage platform. But if I need to publish something publicly—promos or educational content—I have to upload separately to YouTube, VK, and Kinescope. Naturally, this multiplies content administration time exponentially.”

Interviewees noted that accessibility issues with educational and research materials began immediately after the war started and Western companies and institutions imposed sanctions.

“The worst years were 2022 and 2023,” said the science communication instructor. “Everything collapsed at once: data journalism, visualization tools. There were—and still are—no Russian-made programs or services even remotely close to the required level. We adapted somehow, mostly via VPNs, since there’s no alternative. Then in 2024, Russian-side blocking intensified. And here’s another problem—the incompetence of IT staff: any glitch at any node affects the entire system. Once, during a lecture in central Russia, a link worked fine, but students in the Urals couldn’t open it. Turned out their local provider had blocked not just court-mandated addresses but the entire subnet mask. And this kind of thing happens all the time.”

Our interviewees recalled that alongside now-inaccessible work programs and databases, they also lost access to paid services not directly related to science, such as antivirus software or Grammarly. While their unavailability isn’t catastrophic, it still creates technical headaches.

Unavailable, slow, yet essential

The YouTube blockade triggered an outpouring of negative commentary. Russians (at least across various social networks) have been expressing outrage over losing access to favorite programs, TV series, and other video content. But for scientists engaged in public outreach and educators, the YouTube block has become a genuine crisis – as it has for students passionate about their subjects.

“Until recently, we had access to countless instructional videos,” shares a third-year medical student. “Now we can’t even watch tutorials on proper injection techniques.”

“YouTube spoiled us with an abundance of high-quality educational and popular science content, including international material,” writes one of our readers. “Lectures by leading global scientists, conferences, instructional materials – even research methodology guides – this was all created by the global community. Now this entire repository is off-limits to Russian students and researchers. Russian science communicators are also losing a vital platform. Even if they migrate content to Russian services, loyal followers might find them, but attracting new audiences will slow dramatically. No Russian platform currently matches YouTube’s reach, functionality, recommendation algorithms, or quality. The existing intellectual elite will keep consuming popular science content, but this demographic won’t expand.”

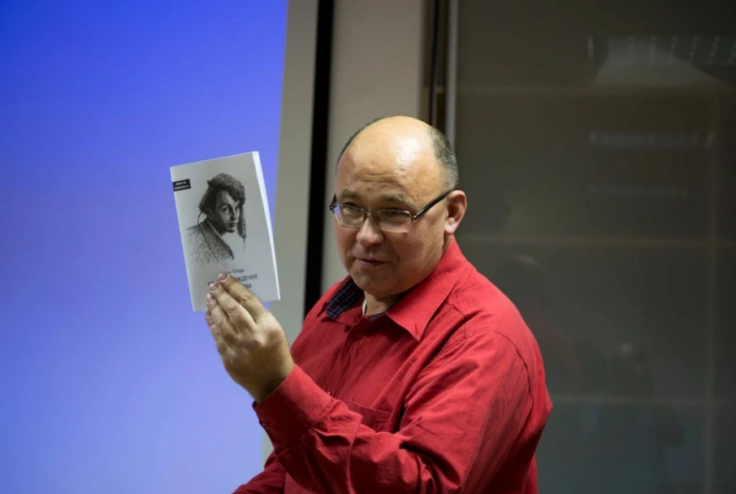

We also spoke with prominent science communicators who run YouTube channels. The GetAClass channel doesn’t quite fit the traditional mold of science outreach.

“We’re closer to being a video textbook,” explains Andrey Shchetnikov, the channel’s host and creator. “Of course, those who really want to find us still can. But that segment of our viewership was always small and remains so now. Views for ordinary, non-viral videos have dropped by about two-thirds, from roughly 20,000 to 7,000. Though I’m not sure this stems solely from YouTube’s block in Russia. Over the past year, we’ve made some questionable decisions ourselves, and the algorithms may have responded strongly to that.”

“For my direct scientific work, there aren’t major issues, but problems arise when I try to reach the public,” says a prominent science communicator, educator, and researcher who requested anonymity. “In December 2024, views dropped by nearly half—at least 40%! For the Russian audience, only those with VPNs remain. I see comments like: “Sorry, we can’t watch—everything’s slowed down for us. All we have left are the comments.” So they’re still participating by reading and adding comments. Dedicated viewers find ways, but the problem is with new audiences—those who’d stumble upon interesting content and later become regular viewers. That growth-driving audience segment has significantly shrunk.”

Sergey Popov, a professor at the Russian Academy of Sciences, confirms declining viewership for Russian-language science content, both on his channel and others he’s contributed to:

“In recent years, YouTube has arguably served as the primary platform for science communication in Russia. In my view, it surpassed popular science books, articles, and websites in terms of audience size, content diversity, and numerous other metrics. Viewers naturally gravitated toward the most accessible format, and content creators focused their efforts accordingly. Yet most video producers – for various practical and ideological reasons – show no immediate inclination to abandon YouTube, nor are they likely to in the foreseeable future. While VPNs currently prevent a complete shutdown of this vital communication channel, the restrictions have significantly diminished its reach. This gradual audience erosion will inevitably lead to some channels closing altogether, others reducing their output frequency, and still others compromising on production quality.”

Hope in Internet Providers

An unexpected development emerged from a Siberian university, where YouTube remains fully accessible on campus. The exact reason behind this exception remains unclear—whether it stems from unique arrangements with the institution’s internet service provider or technical workarounds implemented by the university’s IT specialists. Out of concern for potentially jeopardizing this rare access, we have chosen not to disclose the university’s identity or request an official statement regarding its unusual digital freedom.

Most of our interviewees expressed little optimism when asked about potential solutions or future developments. Many noted that in recent years, Russian citizens have become adept at finding loopholes and workarounds to bypass restrictions and blocks. As a result, most pin their hopes on either new methods to circumvent YouTube blocks, or improvements in VPN technology and reliability. A smaller contingent maintains hope that internet providers might devise clever technical solutions to circumvent these restrictions.

“I see many people are simply afraid to act,” observes Sergey Popov. “If every parent or grandparent whose child lost access to favorite YouTube cartoons wrote to their local representative, lawmakers would be flooded with millions of letters. But this isn’t happening. My followers tell me, ‘Sure, you can politely write to your deputy opposing the YouTube ban—but then they might come after you.’ Maybe it’s paranoia, but it’s real, and we have to accept it as reality. It reminds me of that saying: ‘Are you for or against? Just remember—there’s a law against being against.’”

Russian science communicators, researchers, educators, students, and enthusiasts now find themselves in a position where they must seek loopholes and workarounds just to maintain their work at a high standard. This demands extra effort and time, erodes quality, and limits opportunities. None of those we spoke to view this as normal—nor does anyone wish to return to a technological past.

Support T-invariant’s work by subscribing to our Patreon and choosing a donation tier.