In 2015, the archives of the Max Planck Society—one of Germany’s and the world’s leading scientific organizations—revealed human brain specimens illegally obtained in the 1940s. In 2020, documents exposed how the Kiel Institute for the World Economy aided the Wehrmacht’s conquest of Europe. Then, in 2022, Humboldt University published a study detailing how its own researchers had helped plan war crimes. Why, eight decades after WWII and the fall of the Nazi regime, does German academia continue to unearth such horrors? Can one be complicit in crimes without pulling a trigger—simply by optimizing war economies, promoting pseudoscience, or mass-producing politically expedient research—all while claiming that “science is apolitical”? These questions are explored in an investigative report by Natalia Supyan, PhD in Economics and German studies specialist.

If the German intellectuals, if all the men of name and international reputation:

physicians, musicians, pedagogues, writers, artists,

had unanimously risen against this disgrace,

if they had proclaimed a general strike,

many things would not have happened as they did.

Everyone, provided he was not by chance a Jew,

was always faced with the question: ‘Why, actually?

The others are cooperating. It can’t be so bad after all

Thomas Mann, English Translation (by Heinz Norden, 1945)

Racially Pure

Following Germany’s defeat in World War I, German science—which had flourished in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and once aspired to global dominance—inevitably declined. The pervasive national crisis extended to universities: their financial situation deteriorated, and faculty members, particularly younger ones, became part of an “academic precariat,” struggling to make ends meet with little hope for career advancement. Like many other segments of society, professors felt humiliated, rejected the values of the Weimar Republic, and largely embraced conservative ideologies. Their gaze was fixed on the prosperous imperial past. All of this made universities fertile ground for the rise of radical nationalism.

Many professors joined the Nazi Party (NSDAP) even before its seizure of power[1] in 1933, and within months, universities voluntarily pledged allegiance to the new regime. The “Führerprinzip” (leadership principle), introduced in 1935, stripped higher education institutions of their autonomy, placing rectors under the direct authority of the Reich Ministry of Science, Education, and Culture. Prioritizing ideological loyalty over academic qualifications in the selection of university leaders often led to misguided appointments, triggering internal conflicts and—contrary to the regime’s original intent—undermining the very governance of higher education.

The National Socialist German Students’ League (NSDStB), established in 1926 on Hitler’s orders, gained significant influence. By 1931, it had secured an absolute majority in student government elections across 28 universities, effectively taking control of the entire student movement. Students, who had enthusiastically embraced Nazi ideology and even donned NSDAP uniforms before the party’s rise to power, quickly became a driving force behind Gleichschaltung[2] (coordination). In spring 1933, the NSDStB organized the “Action Against the Un-German Spirit,” culminating on May 10 with public book burnings in over 20 university towns (similar events took place in 70 cities between March and October 1933). Libraries banned the lending of works by blacklisted authors, and universities set up collection points where students were expected to surrender books from their personal libraries that appeared on the prescribed lists. The so-called “German spirit” was deemed under threat from socialist and pacifist writers—but above all, from scholars, journalists, and authors of Jewish origin.

Antisemitism had been extraordinarily strong in German universities long before it became official state ideology. Both faculty and student fraternities had espoused extreme nationalist views during the Imperial era, and in the new, liberal, and emancipated Weimar Republic, they saw themselves as an exclusive caste—guardians of traditional values. This sentiment persisted even during the relatively prosperous “Golden Twenties” (1924–1929), when Jewish scholars, particularly those associated with Social Democrats, faced hostility in academic circles.

The deliberate Aryanization of German universities began as early as spring 1933. In April, the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service was enacted, barring Jews from public sector employment. This was soon followed by the Law Against the Overcrowding of German Schools and Universities, which imposed a strict 1.5% quota on the admission of “non-Aryan” students.

For example, at Heidelberg University, the number of Jewish students plummeted from 180 at the beginning of 1933 to just five by 1937 – the following year, none remained at all. Between 1933 and 1940, 59 faculty members with doctoral degrees (29% of the teaching staff) were dismissed on “racial” grounds; among tenured professors, the proportion reached 40%. At Berlin University, 35% of faculty members were dismissed between 1933 and 1945, while Frankfurt University saw 37% purged. Across Germany as a whole, approximately 20% of all academics lost their positions during this period.

The discriminatory laws affected not only universities—though they suffered the most from the new regime’s interference—but also scientific organizations. The Kaiser Wilhelm Society (KWG)[3] dismissed over a hundred scholars, including 35 institute directors. However, its crucial role in rearming the Reich allowed the KWG to retain self-governing structures and staff until 1937.

Jewish researchers at academies of sciences only came under the scrutiny of the Reich Ministry of Science in 1938. Unlike universities, which trained the new Germany’s young cadres, the academies drew little attention from party officials, granting them marginal autonomy. Nationwide, an average of 14.3% of scholars and faculty lost their positions—approximately 90% due to “racial” reasons and another 9.3% for political ones.

In July 1933, the Law on the Revocation of Naturalization and Deprivation of German Citizenship was enacted specifically to target “emigrated traitors.” It authorized the stripping of citizenship from “Reich subjects abroad whose… behavior, by violating their duty of loyalty to the Reich, has harmed Germany’s interests.” As the policy of Aryanization forced numerous Jewish scholars into exile, universities exploited this new legislation to revise the procedures for awarding and revoking doctoral degrees.

All those who left Germany and were denaturalized were automatically deemed “unworthy” of holding a German doctorate. Furthermore, degree revocation proceedings were initiated against anyone convicted of: treason, “racial defilement”, listening to “enemy radio broadcasts”, “undermining military morale”, desertion, performing abortions, homosexuality, currency violations.

Between 1933 and 1945, approximately 1,700 cases of doctoral degree revocation were documented, though researchers estimate the actual number was at least twice as high. In 70% of cases, the reason was loss of citizenship – meaning they primarily affected Jewish emigrants. The hardest hit were medical and law faculties, followed by departments of political science (Staatswissenschaft) and philosophy.

The internal German resistance against Nazi dictatorship remains relatively unknown outside specialist circles. While books and films about the failed Operation “Valkyrie” have familiarized many with the anti-Hitler conspiracy among high-ranking military officials of the German aristocracy, the reality is that resistance took many other forms: youth protest movements, Social Democrats, Christian opposition groups, organized underground networks, and desperate individuals who stood against the regime. Among them was a circle of scholars and professors centered around several academics from the University of Freiburg—rightly remembered as the “academic resistance.” Their story is explored in Natalia Supyan’s article “Scientists Who Created the Future: Academic Resistance in Nazi Germany.”

On the initiative of the Notgemeinschaft der Deutschen Wissenschaft (Emergency Association of German Science, a precursor to the DFG)[4], the Reich Ministry of the Interior banned research scholarships for non-Aryans in September 1933; Mischlinge (mixed-race individuals) could only receive them in exceptional cases and if no Aryan applicants were available. Starting in the spring of 1933, applicants for research grants were required to complete a supplementary personal questionnaire to prove their “Aryan descent.” By 1934, the list of questions had been significantly expanded to include inquiries about prior political activities.

From 1935 onward, all candidates for university teaching and assistant positions were subjected to political reliability checks, which required Aryan ancestry and unconditional support for the Nazi state. The Notgemeinschaft adopted this practice and began vetting scholarship applicants by submitting inquiries to the National Socialist Association of German Lecturers, local police offices, and the Gestapo. If an applicant failed the racial or political loyalty screening, the content of their application became irrelevant. Thus, professional qualifications and scientific merit were reduced to secondary selection criteria.

By 1937, this policy had already led to a shortage of young, qualified researchers, even as the demand for skilled scientists grew due to the increasing role of science in economic militarization. During the war, the Reich Research Council (RFR) was forced to establish a special department tasked with identifying talented young scholars in universities and specialized higher education institutions.

Ideological Alignment

The Nazification and Aryanization of academia extended beyond structural reforms—such as personnel policies and the governance of science and education—to the very content of scholarship: curricula and research were subordinated to ideological dictates.

Universities began establishing departments of eugenics, racial studies, and ethnology (Volkskunde), while “scientific antisemitism” gained momentum. The University of Tübingen played a pivotal role in legitimizing the Third Reich’s anti-Jewish policies: professors of theology and philosophy, such as Gerhard Kittel and Karl Georg Kuhn, worked in the Research Department for the Jewish Question at the Reich Institute for the History of the New Germany. Meanwhile, staff at the university’s Institute for Racial Biology developed anthropological methods to “identify Jews,” facilitating exclusion policies and, later, their extermination.

“Racial hygiene” and eugenics were taught in all medical faculties, which became the most heavily Nazified sector of Germany’s academic landscape. The close alignment of physicians with Nazi ideology had horrific consequences: abandoning all professional ethics, they participated in euthanasia programs and concentration camp experiments. The term “euthanasia” was applied to campaigns targeting psychiatric patients—between 1939 and 1945, over 200,000 people in Germany were killed with gas, lethal injections, or starvation, with an additional 100,000 murdered in annexed territories. Roughly a third of these victims fell under the T4 program[5]. Physicians themselves selected “unfit” patients and carried out the killings.

Beyond “racial purification,” the euthanasia program aimed to rid the state of “economic burdens” during wartime austerity. It also provided opportunities for medical research, particularly on the human brain. The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Brain Research in Berlin received brain specimens from over 700 euthanasia victims, while the Psychiatric Research Institute in Munich acquired around 200 more. From 1939 to 1944, the two institutes collected a combined 9,000 brain samples.

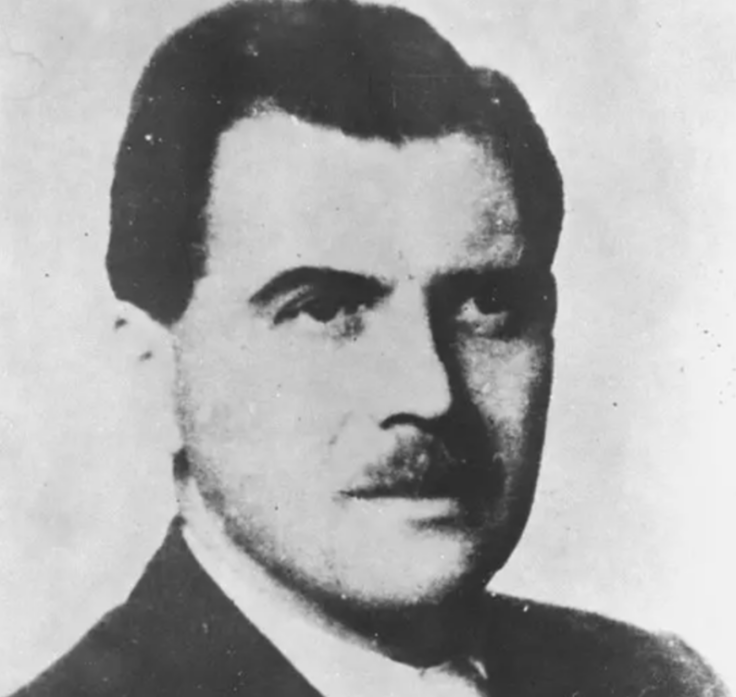

The dehumanization of science removed all barriers to human experimentation. Prisoners of war and concentration camp inmates were subjected to tests of new drugs, deliberate infections with malaria and typhus, hypothermia and pressure experiments (commissioned by the Luftwaffe), and exposure to mustard gas. Most of these “studies” were funded by the Notgemeinschaft der Deutschen Wissenschaft (Emergency Association of German Science), which also financed: Josef Mengele’s twin experiments at Auschwitz-Birkenau, the work of Karl Brandt, Reich Commissioner for Health (later executed in the Nuremberg Doctors’ Trial), geneticist Otmar von Verschuer, who submitted over 40 grant applications to the DFG while working at Frankfurt University and the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics. In reports, Verschuer openly admitted obtaining blood samples from his assistant, Mengele, at Auschwitz.

In 1939, Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS and Reich Commissioner for the Consolidation of German Nationhood, initiated a large-scale interdisciplinary (and undeniably criminal) project—the Generalplan Ost (“General Plan East”). The plan’s development involved numerous German scholars and outlined a comprehensive framework for the legal, economic, and spatial reorganization of territories Germany intended to occupy after victory in the war. It envisioned the colonization and “Germanization” of parts of Eastern Europe (Poland and the USSR), alongside the forced displacement and extermination of 30–40 million indigenous inhabitants.

Konrad Meyer, an agrarian scientist and one of the plan’s chief coordinators, received over half a million Reichsmarks from the DFG (which, as today, routinely reviewed applications and allocated funding) between 1941 and 1945. These funds supported research by economists, administrative lawyers, sociologists, psychologists, architects, agricultural scientists, and spatial planners. To ensure seamless coordination, an institutional framework was established: the Reich Office for Regional Planning (RfR), founded in 1935, and its subordinate university-based working groups were tasked with aligning all scholarly activities with Nazi Party objectives.

In 1941, Konrad Meyer wrote: “Our planning cannot proceed without scholarly collaboration and sustained close ties to universities. Yet I speak of a science that finds its purpose in serving the Volk, rooted in the forces of blood and soil. What we require is not a science preoccupied with abstract generalizations, but one dedicated to practical application—a science that does not merely document the past but actively and foresightedly shapes the future. […] The political mission of our scholarship is embodied precisely in the universities’ hands-on engagement with settlement planning.”

A core component of the Eastern European “modernization” plans was increasing agricultural productivity—unsurprisingly, agricultural sciences, alongside medicine and chemistry, ranked among the top three recipients of DFG funding. The blueprint called for resettling three million ethnic Germans in the newly occupied territories, complete with newly constructed towns, villages, roads, and canals. The scholars engrossed in Generalplan Ost appeared wholly absorbed in designing infrastructure for seemingly uninhabited lands. Whether they deliberately ignored or casually accepted the expulsion and murder of indigenous populations remains unclear—yet their work normalized these crimes.

The plan was finalized in 1942, coinciding with the war’s turning point. As Germany’s eastern offensive stalled, Generalplan Ost was never implemented.

As head of the Reich Office for Regional Planning (RfR), legal scholar, and academic functionary—and at the time, rector of the University of Kiel—Paul Ritterbusch spearheaded the 1940 initiative “Kriegseinsatz der Geisteswissenschaften” (War Mobilization of the Humanities), also known as “Operation Ritterbusch.” This project served a critical ideological mission: over 600 scholars from various disciplines and universities enthusiastically collaborated to provide an academic foundation for the Nazi vision of a “New European Order”—the intended outcome of the war.

Under the slogan,”The world’s best soldier must be supported by the world’s best scholar,” they worked “for the Reich and Lebensraum.” Philosophers, Orientalists, geographers, legal scholars, Germanists, historians, and cultural theorists produced 67 books and 43 monographs, largely propaganda pieces, as part of the project. The DFG covered all costs—publication expenses, conference and exhibition funding, and 50 research grants.

Another major research organization of the Third Reich, whose work was purely pseudoscientific in nature, was the Ahnenerbe (Forschungsgemeinschaft Deutsches Ahnenerbe, the Research Society for German Ancestral Heritage). Founded in 1935 by SS Reichsführer Himmler and the Nazi theorist-mystic Hermann Wirth, the society was tasked with finding scientific proof of “Aryan racial superiority.” Under its auspices, hundreds of scholars studied German folklore and ancient Germanic history, conducting anthropological, archaeological, and historical research. Ahnenerbe researchers sought to validate Hans Hörbiger’s Welteislehre (World Ice Theory) and attempted to prove the existence of a millennia-old Germanic religion through projects like Wald und Baum in der arisch-germanischen Geistes- und Kulturgeschichte (“Forest and Tree in Aryan-Germanic Intellectual and Cultural History”). Additionally, they propagated Nazi ideology and participated in the looting of artworks from occupied territories.

In 1937, Himmler rebranded the Ahnenerbe as the Forschungs- und Lehrgemeinschaft (“Research and Teaching Society”) and appointed Walter Wüst, an Indologist from the University of Munich, as its new president. Research now extended beyond Germany into the broader “Indo-Germanic” sphere—most notably, Ernst Schäfer’s 1938–39 expedition to Tibet. Funding for these unconventional projects came from the DFG (German Research Foundation), which received over 60 grant applications from the Ahnenerbe.

Himmler’s frequent special assignments to Ahnenerbe staff reveal his self-styled enthusiasm for science: searching for gold in German rivers, breeding cold-resistant horses, or promoting folk medicine. A March 1944 letter to Wüst illustrates this: “In future weather studies… I request you note the following fact: The roots or bulbs of the autumn crocus lie at varying depths underground depending on the year. The deeper they grow, the harsher the winter; the closer to the surface, the milder. The Führer himself brought this to my attention.”

By 1942, the Ahnenerbe had been absorbed into Himmler’s Personal Staff as Amt A (“Department A”), which by the war’s end comprised around 45 scientific divisions. Under its umbrella, the Institut für Wehrwissenschaftliche Zweckforschung (Institute for Military Scientific Research) was established, headed by Wüst’s deputy, Wolfram Sievers. Its primary “research” involved human experimentation, chiefly on concentration camp prisoners.

The Ahnenerbe sought to monopolize scientific policy, research, and ideological indoctrination but faced competition from rival entities—notably Aktion Ritterbusch. Both organizations promoted the militarization of humanities scholars, centralized control of science, and the creation of a German-centric European intellectual space—a common feature of the bloated Nazi bureaucracy, where overlapping institutions endlessly duplicated one another’s work.

“Everything for Germany!”

Scientists eagerly took on not only ideologically driven tasks but also more tangible, pressing objectives—primarily addressing severe resource shortages, fostering development under autarky, and enhancing the efficiency of the wartime economy.

Andreas Predöhl, an economist, academic, and rector of the University of Kiel (1941–1945), headed the “Political Economy” division of the War Employment of the Humanities project and led the university’s territorial planning working group. From 1934 to 1945, he also directed the Kiel Institute for the World Economy (Institut für Weltwirtschaft, IfW Kiel). Having replaced a less politically compliant predecessor, he began close collaboration with the Wehrmacht even before the war.

Just days after Germany’s invasion of Poland, he wrote: “The Institute is fully committed to tackling fresh, urgent tasks and maintains a close—almost intimate—telephone liaison with the most relevant authority at this moment: the Wehrmacht’s Military Economic Command.” The Institute produced over two thousand confidential reports detailing the economic potential of countries the Reich intended to absorb into its Lebensraum (“living space”).

Data on grain reserves, petroleum products, steel production, raw material deposits, and infrastructure of these countries formed the strategic foundation for plans of aggressive warfare and the establishment of a European “greater economic sphere” – invariably subordinated to the Reich. The Kiel Institute worked relentlessly on developing concepts to enhance Germany’s economic autarky, proposed reorganization schemes for occupied Polish territories, and rapidly evolved into an indispensable component of the regime and its political machinery.

During the Institute’s 25th anniversary celebration in 1939, Schleswig-Holstein Gauleiter Heinrich Lohse commended the scholars for their dutiful service: “…it was through their initiative that the work became imbued with the National Socialist spirit. Whereas before the [NSDAP’s] rise to power the Institute served as a haven for liberal thought, it now stands as the primary and singular demonstration of how National Socialist economics provides the most expansive field for scholarly inquiry. Your work unfolds away from public scrutiny – quietly, as befits all scientific endeavor. Yet the Institute’s achievements, though visible only to a select few, ultimately serve the common good.”

The IfW’s ostensible political neutrality and maintenance of extensive foreign connections enabled it to supply the regime with specialized expert intelligence, while potentially operating as a node within an international espionage network.

The Institute for Business Cycle Research (today known as the German Institute for Economic Research, DIW Berlin) also actively collaborated with the Nazi regime. Its founder, economist and statistician Ernst Wagemann, fell out of favor in 1933 and was dismissed from all positions. However, he quickly adapted to the new political reality, joined the NSDAP, and was reinstated as the institute’s director. The IfK’s research became instrumental in wartime economic planning, producing numerous reports on topics such as labor allocation, raw material procurement, and the food industry. Moreover, the institute was indirectly complicit in the exploitation of forced labor and mass killings in occupied territories. In 1938, an industrial department was established within the IfK, tasked with developing input-output analysis methods for arms production planning. This department played a particularly significant role after 1942, when it began working directly under the Reich Ministry for Armaments and War Production. Its head, Rolf Wagenführ, later led the planning statistics division within the ministry’s Planning Office. Wagenführ’s key contribution to optimizing the wartime economy lay in his use of a dynamic input-output model, which—for the first time—harmonized sectoral production plans while accounting for all relevant factors.

Close coordination between the military, industry, and academia had already emerged in Germany during World War I, when the state faced similar challenges: securing raw materials under blockade conditions and modernizing arms production. Now, under total militarization, the Reich once again relied heavily on experts in technical and natural sciences. Financial support from the DFG and RFR[6]—both linked to the Army Weapons Office (HWA)—was directed toward research deemed critical for fulfilling the Four-Year Plan: the Reich’s rearmament and preparations for war.

For instance, the Faculty of Defense Technology at Berlin Technical University (then known as the Berlin Institute of Technology, TH Berlin) effectively became a research laboratory for the Army Weapons Office (HWA). The dean of this specialized faculty was General of Artillery and Doctor of Engineering Karl Becker, who would later assume leadership of the HWA itself in 1938.

In 1934, Becker established a rocketry working group led by physicist Erich Schumann. University professor and civil engineer Wilhelm Loos contributed to HWA construction projects, while another faculty professor, explosives specialist Günther Braunsfurt, conducted research for the Office. Physicists and chemists from Berlin Technical University worked at the Peenemünde research center, where the world’s first ballistic missile, the Aggregat-4 (better known as the V-2)[7], was developed.

The working group also included experts from other technical universities, including TH Dresden and TH Darmstadt. The latter provided numerous specialists in engine design, radio transmission technology, ballistics, and staff from its Institutes of Inorganic Chemistry, Physical Chemistry, and Applied Mathematics.

Hitler himself placed great faith in German chemists, declaring: “Thanks to the genius of our inventors and chemists…we will find ways to become independent of importing substances that we can produce or substitute ourselves.” This conviction materialized in state-funded chemical research programs aimed at securing synthetic rubber, gasoline, plastics, pharmaceuticals, fertilizers – as well as explosives, smoke munitions, and chemical weapons. Under these circumstances, every chemist was valuable to the Reich, and the German Chemical Society actively collaborated with the Wehrmacht.

In 1938, chemist Otto Hahn and his assistant Fritz Strassmann achieved the first successful nuclear fission of uranium by neutron irradiation, releasing substantial amounts of energy. By 1939, Germany had launched its nuclear program, the so-called Uranprojekt. Scientists quickly recognized uranium’s military potential and reported their findings to the Army Weapons Office.

That same December, Nobel Prize-winning physicist Werner Heisenberg wrote: “The enrichment of uranium-235…represents the sole method for producing explosives whose power would exceed by several orders of magnitude the most potent conventional explosives available today.” The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics, headed by Heisenberg, became the project’s principal research center.

The initiative mobilized approximately 100 scientists from more than twenty institutions, including 15 universities and technical colleges. Key participants—alongside Hahn and Heisenberg—included physicists Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker, Karl Wirtz, Kurt Diebner, Walther Gerlach, and Robert Georg Döpel.

According to RFR (Reich Research Council) documentation, all funding for nuclear physics research was earmarked for “tasks that would decisively influence the war’s outcome.” However, by 1942, scientists acknowledged that creating a nuclear explosive device—an atomic bomb—remained impossible in the near term, not least for economic reasons.

Despite this setback, the program continued. The research group constructed an experimental nuclear reactor, though they ultimately failed to initiate a sustained chain reaction. During the Allied Operation Epsilon, the Haigerloch reactor was dismantled, project documentation seized, and ten German scientists interned in England.

Very Dirty Water

Following Germany’s surrender and the division of its territory into four occupation zones, each military administration began implementing the policy of the “Four Ds” agreed upon by the Allies at the Potsdam Agreement. These principles entailed: demilitarization, denazification, democratization, decentralization of Germany[8].

At the institutional level, denazification proceeded relatively swiftly and successfully across all occupation zones: the Nazi Party (NSDAP) was banned, all Third Reich laws repealed, and leading war criminals removed from public life, prosecuted and punished through the Nuremberg Trials and subsequent proceedings. However, the broader “mass denazification” effort—aimed at purging Nazis from government, politics, industry, and education while fostering German societal accountability for wartime crimes—proved far less effective. Many experts consider it an outright failure.

In the Soviet occupation zone, denazification took a particularly harsh form, effectively becoming a political purge coinciding with regime change. Alongside Nazis, other opponents of Soviet authority were targeted. Tens of thousands were interned in NKVD special camps, where many perished. Yet, German specialists deemed valuable to the USSR avoided punishment, and former NSDAP members who demonstrated loyalty to the communist regime later assumed prominent positions in the GDR.

The approach in the Western zones differed starkly. The American and British military administrations distributed millions of detailed questionnaires (Fragebogen) to the adult population, which were then reviewed by denazification tribunals. Respondents were classified into five categories: major offenders (Hauptschuldige), activists (Belastete), lesser offenders (Minderbelastete), “fellow travelers” (Mitläufer—nominal Nazis), exonerated persons (Entlastete).

By early 1946, the tribunals were overwhelmed, prompting the U.S. zone to transfer the process to German-led courts in March 1946—a move followed by the British in October 1947. Critics argue the Western Allies prioritized reintegrating former Nazis into society over rigorous accountability. The French zone adopted an even more lenient approach, focusing on pragmatic stability rather than ideological purification.

The courts prioritized minor Nazi cases—those easier to adjudicate—while deferring serious crimes until 1947. This delay allowed many perpetrators to flee abroad; those who remained later faced more lenient German tribunals. Numerous high-ranking offenders escaped punishment altogether, and thousands dismissed in the immediate postwar years gradually returned to their positions, including in government. By 1950, when denazification officially ended, 3.6 million people in the Western zones had undergone review. Only 25,000 were classified as major offenders, activists, or lesser offenders (categories 1–3). 1 million were deemed nominal “fellow travelers” (Mitläufer). 1.2 million were exonerated. Even convicted members of the NSDAP elite, SS, and security police often received mere fines or two-year prison sentences.

Denazification earned the nickname Mitläuferfabrik (“fellow traveler factory”) as defendants scrambled to “launder” their records. They procured witnesses to testify they had never been true Nazis, securing Persilscheine—”Persil certificates” (named after the detergent brand)—to “wash” their past clean. A cycle of mutual exoneration emerged: former Nazis reinstated in civil service issued clearance certificates to colleagues, while incriminating documents mysteriously vanished. As historian Ulrich Herbert observed: “The great injustice lies in the fact that most Nazi criminals—including genuinely brutal, horrific murderers—emerged unscathed. This remains a burden Germany carries to this day.”

This haphazard, inequitable process fostered little collective remorse among Germans. Many believed the Nuremberg Trials had sufficiently addressed guilt and demanded denazification’s swift conclusion. After the founding of the FRG, pressure mounted, so 1949 and 1954 amnesty laws pardoned most convicted Nazis, expunging their records. As well as, Article 131 of the Basic Law reinstated nearly all civil servants purged by the Allies.

During a press conference in 1952, West Germany’s first Chancellor Konrad Adenauer faced sharp criticism for appointing former Nazi officials to high-ranking government positions—including within the Federal Chancellery itself. His now-infamous response laid bare postwar Germany’s moral compromise: “One doesn’t throw tainted water until one has clean!”

There was little urgency to “drain this tainted water” from academia. As in other sectors, the immediate postwar years saw mass dismissals of professors affiliated with National Socialist organizations (averaging 70% of faculty). Yet by the early 1950s, nearly all had been quietly reinstated – in some cases, their positions had been deliberately left vacant awaiting their return. Outcomes varied by institution: the University of Bonn stood as a rare denazification success story, where few former Nazis managed to reclaim their professorships.

The Berlin Institute of Technology initially took a firm stance in 1945, purging faculty with Nazi ties—but soon faced a staffing shortage and increasingly made exceptions when professional qualifications outweighed political background. After the amnesty and the official end of denazification, however, even those implicated in Nazi crimes were readmitted. One such case was Franz Bacher, a professor and head of the Institute of Organic Chemistry, a Nazi Party member since 1931, and a key figure in the university’s Reich Ministry of Science and Education. In 1945, he was dismissed with the following justification: “Lacks academic qualifications. Was an SS member and active party loyalist, appointed solely for ideological reasons. In the ministry, he consistently pushed for fellow Nazis to be hired.” Nevertheless, by 1953, he was back at the university, teaching organic chemistry until his retirement.

Yet Bacher’s case was relatively benign—a mere Nazi bureaucrat slipping back into academia. Far worse were the outright monsters and their eager accomplices who resumed their careers with little resistance.

Hans Fleischhacker, an SS Obersturmführer and researcher at the University of Tübingen’s Institute of Racial Biology, studied fingerprints of Jews in the Łódź Ghetto, earned his doctorate in 1943 based on this work, and later conducted selections at Auschwitz for the “Jewish skeleton collection.” Dismissed by French occupation authorities in 1945, he was classified as a “fellow traveler” by 1948, and by 1950, he was working as an expert for the German Anthropological Society. In the early 1960s, he returned to the University of Tübingen as an assistant at the Institute of Anthropology, later moving to a similar post at Goethe University Frankfurt, where he remained until retiring in 1977. During the era of Nazi hunter Fritz Bauer, Hesse’s attorney general, an investigation was launched into Fleischhacker—but in court, he claimed ignorance of the fate of those he measured in Auschwitz (i.e., their murder for the Ahnenerbe’s museum collection) and was acquitted. Students boycotted his lectures, yet Fleischhacker insisted he saw “no reason to stop working.”

His Tübingen colleague, the aforementioned antisemitic ideologue Professor Kuhn, had organized anti-Jewish boycotts, justified Kristallnacht pogroms, and looted Jewish libraries from the Warsaw Ghetto. Despite this, in 1948, he was cleared of charges, appointed as a professor, and went on to teach New Testament studies at the universities of Göttingen, Mainz, and Heidelberg. By 1964, he was elected to the Heidelberg Academy of Sciences.

The eugenicist geneticist Otmar von Verschuer, head of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, specialized in “hereditary biology and racial hygiene” and served as an expert in sterilization trials.

Funded by the DFG, he conducted medical and genetic experiments—including on Auschwitz prisoners, facilitated by his collaboration with camp doctor Josef Mengele. “It is vital,” Verschuer once declared, “that our racial policies—including those regarding the Jewish question—gain an objective scientific foundation recognized by broader circles. […] Our science must be a sharp sword in the right hand!” Yet in 1946, a tribunal deemed him merely a “fellow traveler,” fining him 600 Reichsmarks. By 1951, he was fully rehabilitated, becoming a professor at the University of Münster and director of its Institute of Human Genetics. A year later, he was elected chairman of the German Anthropological Society.

“It is an exceptional and rare fortune for scientific research when it coincides with an era that grants it universal approval, and when its practical applications become the foundation of state policy,” declared Professor Eugen Fischer, renowned expert in medicine, anthropology and eugenics, speaking about racial policies.

In the early 20th century, Fischer had already gained notoriety for his expeditions to German colonies in Africa and publications on racial hygiene. During the Third Reich, he served as rector of Berlin University (now Humboldt University) and director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, consistently supporting National Socialist policies of discrimination and mass murder.

Together with his colleagues at the institute, Fischer orchestrated in 1937 the forced sterilization of 800 children born to German women from relationships with French colonial troops stationed in the occupied Ruhr region. Despite this, by 1952 he had been made an honorary member of the German Anthropological Society, the German Anatomical Society, and the Society for Constitutional Research. His academic papers and textbooks continued to be published well into the 1960s, while his theories remained part of university curricula across Germany.

Psychiatrist and geneticist Ernst Rüdin shared this fervent enthusiasm for implementing racial hygiene policies, whose “importance became clear to all awakened Germans through the political work of Adolf Hitler.” As early as 1903, he had advocated for the compulsory sterilization of the mentally ill—a position he later institutionalized as head of the German Research Institute for Psychiatry. Serving as chairman of the Society of German Neurologists and Psychiatrists, Rüdin became one of the most influential scientists legitimizing Nazi policies in medicine and public health. He played a direct role in drafting racial hygiene legislation and, under the T4 “euthanasia” program, provided the scientific framework for selecting victims, including children deemed “unworthy of life.”

After the war, Rüdin was dismissed and placed under house arrest. Denazification proceedings first classified him as a “minor accomplice,” then downgraded him to a mere “fellow traveler.” In court, he insisted his work had been purely scientific, completely divorced from ideology—a claim supported by character testimony from fellow scientists, including Max Planck. Released without consequence, Rüdin died in 1952. The Institute of Psychiatry’s obituary memorialized him as “one of the most eminent pioneers of psychiatric genetics.”

Konrad Meyer, the chief architect of the inhumane Generalplan Ost and a direct subordinate of Heinrich Himmler, had drafted proposals for the resettlement of occupied Polish territories. In May 1945, he was arrested and interned, and in 1948, he stood trial at Nuremberg for racial crimes. He faced three charges: crimes against humanity, war crimes, and membership in the criminal SS organization. His defense argued that Generalplan Ost was merely an academic exercise, disconnected from actual policy, and that Meyer had no knowledge of its implementation. In the end, he was convicted only on the third count and sentenced to two years and ten months in prison—time he had already served.

After briefly working at an agricultural business in his hometown of Einbeck, Meyer—thanks to a former colleague who had also escaped punishment—secured a teaching position at Hanover Technical University in 1954. By 1956, he was a full professor of agricultural and regional planning. That same year, he joined the Academy for Spatial Research and Regional Planning, an institution that brought together the “elite” of the Nazi-era Reich Working Group for Spatial Research. He published extensively, supervised dissertations, and even secured a 4,400 Deutsche Mark grant from the DFG (just as he had in the 1930s and ’40s!) for aproject led by his student Hermann Böke.

Until the end of his career, Meyer maintained his innocence, casting himself as a victim. Yet his academic work remained steeped in the same ideology that had shaped Generalplan Ost: he wrote of “white racial superiority,” recycled racist stereotypes, and promoted grandiose territorial expansion schemes—echoes of the very plans that had once served genocide.

Economist Andreas Predöhl, under whose leadership the Kiel Institute for the World Economy actively collaborated with the Wehrmacht, was dismissed by British military authorities in December 1945. Cleared in denazification proceedings, he returned to the University of Kiel by December 1947 and regained his professorship in 1949. By 1953, he was heading the Institute of Transport Sciences at the University of Münster, later serving as its rector (1960–1961). In 1964, Predöhl became the founding director of the German Overseas Institute (today’s GIGA, the German Institute for Global and Area Studies).

A genuinely talented economist, he was consulted as an expert by both the DFG and West Germany’s Social Democratic Party (SPD)—notably flexible in its dealings with former Nazis. Predöhl contributed to the SPD’s rebranding efforts, including the pivotal Godesberg Program[9]. An early advocate for the European Coal and Steel Community and the broader EEC, he remains a frequently cited theorist of international economic integration.

Yet his vision was not new. During the Third Reich, he had championed a European “large-scale economic space” where all nations would benefit from a “shared order”—though in this model, Germany, as the primary producer and consumer, stood to gain most, while the “artificially created” states of Southeastern Europe were to be absorbed into its Lebensraum.

Predöhl later justified his wartime work: “I had to cultivate the best possible relations with the Nazi regime—but never at the expense of sacrificing scholarly integrity.” He claimed his cooperation aimed to protect his institute and shield staff from frontline deployment.

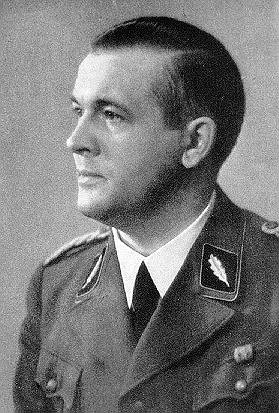

Indologist and SS-Oberführer Walter Wüst, president of the Ahnenerbe research organization and a close associate of Himmler, served as rector of Munich University from 1941. On February 18, 1943, after a two-hour interrogation, Wüst personally handed over Hans and Sophie Scholl—members of the White Rose student resistance group—to the Gestapo after they were caught distributing anti-Nazi leaflets by the university’s administrator. In 1942, philosophy professor Kurt Huber had joined the group, co-authoring their fifth and final leaflet, which urged students to boycott lectures taught by “SS officers and party hacks” and fight for authentic scholarship. The Gestapo tasked classical philologist Richard Harder with analyzing the leaflets’ linguistic style, confirming their academic origin. Huber was arrested on February 27; by March, Rector Wüst had revoked his doctorate as “unworthy.” The Scholls were executed on February 22, 1943, Huber on July 13.

Postwar, Wüst was interned and dismissed. In 1949, denazification courts classified him as an “accomplice,” sentencing him to three years’ labor (already served), loss of pension and voting rights, and a decade-long teaching ban. After appeal in 1950, he was downgraded to “minor accomplice” and by 1951 had regained his professorship, later publishing extensively as an independent scholar.

The Uncomfortable Truth

The rehabilitation of former Nazis relied on an unspoken pact: keep quiet about your past, and society would ignore your crimes—a “don’t ask, don’t tell” arrangement. Postwar German academia cultivated the myth that scholars under the Third Reich had pursued “pure” science, untouched by politics. Collaboration was framed as the domain of mediocre, opportunistic researchers. Otherwise, science itself was cast as Nazism’s victim—forcibly subjugated, never complicit.

This myth remained largely unchallenged throughout the 1960s and only began to shift in the 1990s—by which time most Nazi-era figures had either died or retired. The opening of Stasi archives and the gradual lifting of this veil of silence led to shocking revelations. In 1994, Hans Schwerte, rector of RWTH Aachen University, was exposed as SS-Hauptsturmführer Hans Schneider, a former Ahnenerbe researcher who had been living under a false identity since the war. Stripped of his professorship, state honors, and pension, the Schneider/Schwerte case became emblematic of postwar concealment.

It was only in the last 15–20 years that German academic institutions seriously confronted their past. Universities, research institutes, and scholarly societies began initiating their own investigations—many of the “achievements” of the scientists described above came to light solely through these recent efforts.

In 2001, the German Research Foundation (DFG) launched its fourth attempt to document the true history of its predecessor, the Notgemeinschaft der Deutschen Wissenschaft (Emergency Association of German Science). An independent commission led by Professor Rüdiger vom Bruch (Humboldt University Berlin) and Professor Ulrich Herbert (University of Freiburg) examined the organization’s activities from 1920 to 1970.

The study confirmed—or in some cases revealed for the first time—several damning truths: that nationalist and revanchist ideologies had already dominated German academia before the NSDAP’s rise to power; that after 1933, scientific institutions enthusiastically conducted racial and ideological purges while remaining scholars pledged loyalty to the regime, with resistance being virtually nonexistent; that the DFG had funded both the Generalplan Ost and Josef Mengele’s human experiments; and that postwar DFG remained “a bastion of conservative ideologies and old-regime professors.”Initial findings were published in 2006, but research and documentation continue well into the 2020s.

The Max Planck Society, one of Germany’s most prestigious research organizations, acknowledged its institutional legacy in 1997 by establishing the “History of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society under National Socialism” commission. The investigation revealed uncomfortable truths: most scientists had willingly collaborated with the regime; brain research and psychiatry institutes received specimens from “euthanasia” centers; technical institutes contributed to weapons development; and previously mentioned figures like Eugen Fischer and Otmar von Verschuer were directly complicit in Nazi crimes. The study also documented that between 1939-1945, the Kaiser Wilhelm Society utilized at least 1,000 forced laborers. In 2001, then-president Hubert Markl issued the organization’s first formal apology to survivors of human experiments conducted at Auschwitz. The commission concluded its work in 2007.

However, subsequent inspections in 2015-2016 uncovered a disturbing legacy still present in Max Planck archives – preserved brain specimens and other materials obtained through criminal means. “We are horrified that our archives still contain remains of euthanasia victims who were never properly buried in the 1990s,” stated officials, who launched a new initiative to identify victims, provide dignified burials, and memorialize their stories. These gruesome discoveries were tied to Ernst Rüdin of the German Research Institute for Psychiatry and Julius Hallervorden of the Brain Research Institute, who seamlessly continued their work after 1945.

In 2002, the University of Tübingen established its own working group to examine its Nazi past. Their research confirmed the enthusiastic support most professors had shown for the regime, along with the university’s involvement in forced sterilization programs and use of slave labor. A particularly chilling discovery came in 2009 when researchers found 309 handprints of Łódź Jews – materials used by Hans Fleischhacker for his racist anthropological “research” attempting to “scientifically” distinguish Jews from other people. These artifacts, along with other evidence of university complicity in Nazi crimes, were displayed in a 2014 exhibition titled “In Fleischhacker’s Hands,” named after the SS anthropologist whose dissertation was based on this pseudoscientific work. The exhibition forced a painful reckoning with how academic institutions had legitimized racial ideology.

In recent years, similar critical examinations of institutional pasts have been undertaken by the Universities of Marburg, Hohenheim, and others. A landmark 2022 study commissioned by Humboldt University’s historical commission—Sven Oliver Müller’s “Science Planning War Crimes: Humboldt University’s Role in Developing the Nazi ‘Generalplan Ost’”—provided particularly damning evidence of academic complicity in genocide.

The long-suppressed history of the Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW) came to light through historian Gunnar Take’s 2020 dissertation, “Research for Economic Warfare: The Kiel Institute Under National Socialism.” Notably, IfW supported this independent research by granting full archival access and funding publication—a rare institutional willingness to confront uncomfortable truths.

The German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) is now addressing its own historical gaps. In spring 2025, it will launch a three-year collaborative project with the University of Stuttgart’s Historical Institute, examining not just the Nazi era but also the late Weimar and early Bonn Republic periods. This broader scope aims to trace the roots of scientific collaborationism and its lasting institutional legacies.

Germany’s struggle with collective silence and the suppression of the past is far from over. It persists not only in the critical reassessment of scientific institutions’ histories but also in ongoing efforts to restore historical justice. The University of Tübingen was the only institution to annul all decisions stripping its scholars and alumni of their academic degrees immediately after the war. It wasn’t until the 1990s that other universities followed suit—among them Bonn, Münster, Humboldt University, as well as the universities of Frankfurt, Kiel, and Hamburg. The universities of Cologne, Göttingen, Leipzig, and Würzburg took this step even later, in the 2000s.

This rehabilitation began only 50 years after the war’s end, primarily due to the efforts of students and historians working in university archives. The institutions were reluctant to acknowledge their complicity and, evidently, became willing to do so only when not just the “dark brown” professors—as Germans refer to them—but even the persecuted scholars had passed away. There was no longer a need to look them in the eye: it had all become history.

The Tragedy of the “Apolitical”

“Of course, he was not a Nazi”—this is how German historians often begin their reflections on nearly every prominent scholar who worked under the Third Reich. But then why did so many renowned and ordinary scientists, professors, and university researchers continue to collaborate with the regime, often without even agreeing with its policies?

Let us begin with the fact that after the personnel purges in science and education in 1933, universities and research institutions became a hermetically sealed and virtually sterile structure, where little to no resistance emerged. The remaining employees can be divided into several categories.

The first group consisted of principled, fanatical Nazis devoid of any ethical constraints. They were not numerous, but their presence was enough to tarnish German science—and Germany as a whole—for decades to come.

The second group comprised opponents of the republic—conservatives who longed for the past glory of German science, which in the early 20th century had no global rival. Their sympathy for National Socialism stemmed from a yearning for a “strong hand” that would restore order and secure proper funding for research. They believed the political purges and persecutions were mere transitional costs of a regime change, that the radicalism of the early years would fade, while the new order would endure. Many of them later faced bitter disillusionment.

The third and largest group were the opportunists, the so-called Märzgefallene (“March fallen”)—a term mocking the hundreds of thousands of Germans who rushed to join the Nazi Party after the Reichstag elections in March 1933. Academia, too, had many such figures. They adapted swiftly to the new circumstances, leveraging them for career advancement by complying with whatever was demanded of them.

Finally, the fourth category—which often included genuine, serious scholars—consisted of those who rejected Nazi ideology and may have even resisted it privately but remained within the system out of fear, professional duty, or careerism. They clung to the mantra: “We devoted ourselves to science; we are purely apolitical researchers, never involved in the criminal actions of the National Socialists—we lived only for our work.” Preferring to retreat into “inner emigration,” they avoided overt confrontation.

But was such “neutrality” sufficient when their research contributed to stabilizing the Nazi regime, and their achievements bolstered its reputation? What services did “pure” science render to the regime while seemingly staying within ethical bounds? Could science truly be “apolitical” when it strengthened military capabilities, secured economic dominance, and facilitated the exploitation of occupied territories? Were the coveted scientific breakthroughs worth the irrevocable tarnishing of their moral legacy?

Werner Heisenberg, one of the greatest physicists of the 20th century and a 1932 Nobel laureate, was outraged by the racial laws enacted after the Nazis seized power, which forced colleagues like Albert Einstein, Max Born, and Erwin Schrödinger to flee Germany. Yet he never publicly protested, limiting himself to quiet, bureaucratic resistance. By defending Jewish colleagues, Heisenberg became a target of proponents of “Deutsche Physik” (“German Physics”), who dismissed modern theories as “Jewish heresy.” In 1937, Johannes Stark, a leading figure of this movement, published a vicious attack in the SS newspaper Das Schwarze Korps, branding Heisenberg a “White Jew” (a non-Jew under Jewish influence) and “Einstein’s viceroy” or the “Ossietzky[10] of physics.”

Heisenberg, prioritizing the survival of genuine science, appealed directly to Heinrich Himmler for protection. Though an investigation cleared him, he remained under scrutiny. By 1939, he became a key figure in the Nazi nuclear program. In this role, he lectured abroad—including in occupied countries—where former colleagues now saw him as an enemy and a cog in the Nazi machine. During a 1941 meeting in Copenhagen with his mentor Niels Bohr, their worldviews had diverged so drastically that historians still debate whether Heisenberg offered assistance or recruitment for the uranium project. In 1943, while visiting the Netherlands, he allegedly told physicist Hendrik Casimir: “History itself has ordained Germany to dominate Europe and eventually the world. Democracy lacks the strength to unite Europe. Thus, there are only two options: Germany or Russia. And perhaps a Europe under German rule would be the lesser evil.”[11]

Heisenberg’s colleague, the eminent chemist Otto Hahn (whose discovery made the nuclear project possible), opposed the regime more openly, actively shielding Jewish friends and coworkers. U.S. intelligence files described him as “anti-Nazi,” “pro-democratic,” “honest,” “reliable,” and “disapproving of National Socialism.” Yet as director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry, Hahn inevitably participated in political purges within his organization—remaining, however reluctantly, part of the system. He positioned himself as an apolitical researcher, distancing himself from racist extremes in science. But as many of his peers argued, there was no such thing as “pure” science in the Third Reich.

For thirty years, Otto Hahn worked side by side with the brilliant physicist Lise Meitner, who overcame tremendous obstacles faced by women in science at the time out of sheer dedication to her work. In 1938, just as Hahn, Strassmann, and Meitner’s research team stood on the verge of a major breakthrough, Meitner—being Jewish—was forced to flee Germany for Sweden. Mere months later, Hahn and Strassmann achieved the first successful fission of a uranium atomic nucleus, yet found themselves unable to fully explain their discovery. Despite the risks, they turned to Meitner for help, and it was she who provided the correct theoretical interpretation.

In 1944, Otto Hahn was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, while Meitner wasn’t even mentioned. As she later recalled, her life in exile felt like “living in a desert.” Yet despite her precarious situation, she refused on principle to participate in the American nuclear program.

In an unsent letter to Hahn in 1945, Lise Meitner wrote: “…If only you could see the people who came here from the camps. Someone should have forced Heisenberg and millions like him to look at those camps, at the tortured victims. His appearance in Denmark in 1941 is impossible to forget. <…> This is Germany’s tragedy—that all of you lost any sense of legality and justice. You all worked for Nazi Germany and never even attempted passive resistance. Yes, to ease your consciences, you helped a few persecuted individuals, but you allowed millions of innocents to be murdered. <…> You never lost sleep over it. You chose not to see—it was too inconvenient.”[12] Meitner deeply regretted not leaving Nazi Germany sooner, delaying her departure until 1938. She never returned.

Two of Germany’s greatest physicists, Nobel laureates Max Planck and Albert Einstein, were close friends who visited each other’s homes and often played music together—Planck an accomplished pianist, Einstein a violinist. Yet politically, they inhabited diametrically opposed worlds. While Einstein was a rebellious, staunch republican democrat, Planck embodied Prussian virtues: obedience, duty, and modesty, yearning for the Wilhelmine Germany of the past.

When the Nazis came to power in 1933, Einstein immediately resigned from the Prussian Academy of Sciences, renounced his German citizenship, and left for the United States (never to return). Planck, initially failing to grasp the full scale of the catastrophe, struggled to understand Einstein’s vehement rejection of the new regime. His Prussian upbringing and reverence for the state conditioned him to accept authority without question. At the Academy meeting discussing Einstein’s expulsion, Planck declared: “Through his political behavior, Einstein himself has made his continued membership impossible.” This was not merely Planck’s personal stance but reflected an unspoken rule deeply ingrained in German academia: that scientists must never openly criticize political power. Such “apolitical” posturing—what Thomas Mann had critiqued in his 1918 Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man—was in fact a clearly defined political position. It sacralized the state while clinging to national-conservative values, all under the convenient camouflage of scientific neutrality, allowing its adherents to avoid taking stands on contentious issues.

Einstein could not reconcile himself with the fact that Planck—his elder colleague whom he deeply respected—had chosen to remain within the system, becoming a tool of the National Socialists in the name of preserving German science. “…Even if I were a gentile, under such circumstances I would not have remained president of the Academy and the Kaiser Wilhelm Society,” he wrote in 1934 to his colleague, physicist Ludwik Silberstein. Indeed, as head of Germany’s most powerful scientific organization overseeing all extramural fundamental research, Planck could not have been ignorant of the fact that racial policies and related medical studies had become central themes at many Kaiser Wilhelm Society (KWG) institutes.

Planck himself actively supported and promoted weapons research, even when it violated the Versailles Treaty. In 1933, in a letter to Reich Minister of the Interior Wilhelm Frick, he vehemently denied accusations that “the KWG had abandoned military-political tasks due to pacifist tendencies.” On the contrary, with Hitler prioritizing rearmament, the KWG eagerly placed its resources at the regime’s disposal. Planck invested considerable effort into developing the Institute for Iron Research (Institut für Eisenforschung), which played a pivotal role in strengthening Nazi Germany’s military industry. In 1935, as KWG president, he proudly inaugurated the institute’s new modern facility in Stuttgart—a symbol of how collaboration with the Nazis guaranteed the Society steady funding.

By 1938, when the Reich Ministry of Science demanded the expulsion of all “Mischlinge and those in mixed marriages,” Planck, as secretary of the Prussian Academy of Sciences, circulated a letter to members requesting they disclose if they fell into these categories: “For simplicity, I would recommend filling out the attached questionnaire.” After several members were forced to resign, Planck wrote to them: “…Allow me to express, alongside my profound regret, the Academy’s gratitude for your many years of valuable collaboration.”

It is difficult to say whether there was anything behind this courtesy beyond the formal politeness of a civil servant. We cannot know whether Planck ever considered that all expelled “non-Aryan” scientists were being stripped of their rights, livelihoods, and professions—and that those who failed to flee would end up in concentration camps, while those who emigrated rarely managed to continue their academic careers. Yet Planck certainly regretted that the Academy was losing valuable staff due to racial policies. As early as May 1933, he even attempted to persuade Hitler that expelling prominent Jewish scientists would harm German science—a futile effort, of course.

During a trip to Stockholm in 1943, Planck confided in Lise Meitner: “Terrible things must be happening. We have done terrible things.” By then, he fully understood that he had been serving a criminal state—and soon, that state would come for him, proving that no amount of Prussian virtue could avert tragedy. Planck’s son Erwin, a member of the resistance, was arrested on July 23, 1944, just three days after the failed assassination attempt on Hitler.

Upon learning of his son’s arrest, the 87-year-old Planck traveled to Berlin to plead with Himmler for mercy, insisting on Erwin’s innocence. Accused of high treason and attempting to violently overthrow the Reich’s constitutional order, Erwin Planck was sentenced to death by the People’s Court on October 23. Two days later, Max Planck addressed a desperate appeal to Hitler: “My Führer! I am profoundly shaken by the news that my son Erwin has been sentenced to death by the People’s Court. The recognition of my service to our fatherland—which you, my Führer, have so honorably acknowledged on multiple occasions—grants me the right to hope you will heed the plea of an eighty-seven-year-old man. As gratitude from the German people for my life’s work, which has become an enduring intellectual legacy of Germany, I beg you to spare my son’s life.”

He also petitioned Himmler and the Reich Minister of Justice to commute the sentence to imprisonment. Planck’s influential acquaintances appealed to every possible authority, including Hermann Göring. On November 9, they received word that “the Reichsführer-SS deems a pardon acceptable, substituting the sentence with life imprisonment.” The family clung to hope—until January 23, 1945, when Erwin was hanged at Berlin’s Plötzensee prison, infamous for its executions of political prisoners.

For all six months of his imprisonment, Erwin Planck endured torture and interrogation, pressured to betray fellow conspirators. He never broke.

[1] Here and throughout: Machtergreifung (German: “seizure of power”)—the term refers to the National Socialists’ rise to power on January 30, 1933, when President Paul von Hindenburg appointed Adolf Hitler as Chancellor of the Weimar Republic.

[2] Gleichschaltung (German)—the forced integration of all political, economic, social, and cultural institutions into a single structure subordinated to the ideology of the dictatorial regime.

[3] Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften e.V. (Kaiser Wilhelm Society for the Advancement of Science)—an organization uniting Germany’s leading research institutes from 1911 to 1948. After partial dissolution, it was reestablished as the Max Planck Society.

[4] The Notgemeinschaft der Deutschen Wissenschaft (Emergency Association of German Science), founded in 1920, provided financial support to prominent scholars and research projects. Disbanded in 1945, it was revived in 1949 and renamed Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) in 1951.

[5] The program derived its name from the headquarters of Zentraldienststelle T4 (Central Office T4), the secretive agency overseeing mass killings, located at Tiergartenstraße 4 in Berlin.

[6] The Reichsforschungsrat (Reich Research Council), established in 1937 under the Ministry of Education, centralized control over all fundamental and applied scientific research.

[7] The “V” originated from Vergeltung (German: “retribution”).

[8] Occasionally, a fifth “D” was added—Demontage (dismantling of remaining German industrial infrastructure).

[9] The Godesberg Program—a political manifesto adopted by the SPD (Social Democratic Party) in 1959, marking a ideological shift that transformed the party into a “big-tent” movement until 1989.

[10] Carl von Ossietzky (1889–1938)—German journalist, pacifist, and editor of the anti-militarist Die Weltbühne. Arrested after the Reichstag fire in 1933, he was imprisoned in Sonnenburg concentration camp. Awarded the 1936 Nobel Peace Prize, he died from tuberculosis and camp abuse before receiving it.

[11] See Philip Ball, Serving the Reich: The Struggle for the Soul of Physics under Hitler (2014).

[12] See Ruth Lewin Sime, Lise Meitner: A Life in Physics (University of California Press, 1997).