In August 2025, the promising Target Malaria project aimed at combating malaria using modified mosquitoes was abruptly shut down in Burkina Faso. The country’s government sealed the laboratories, destroyed the insects, and sprayed insecticides, labeling the experiment a threat to sovereignty. Many scientists from around the world called this decision a catastrophe: gene drive technology could have permanently rid Africa of malaria, which claims 600,000 lives annually. T-Invariant has uncovered how a Russian-coordinated disinformation campaign, anti-Western sentiments, and local activists led to the halt of one of the continent’s most promising scientific projects.

Top news on scientists’ work and experiences during the war, along with videos and infographics — subscribe to the T-invariant Telegram channel.

On August 11, 2025, researchers from the non-profit organization Target Malaria released near the village of Souroukoudingan in Burkina Faso about 16,000 male mosquitoes, genetically modified to produce only male offspring. This was the next step in a program to combat malaria that had been operating in the country for 13 years. The project was funded by the Gates Foundation, and its goal was to rid African countries of the disease using gene drive technology, which promotes the spread of desired genes in a population. However, a week after the insects were released, judicial police arrived at the Institut de Recherche en Sciences de la Santé (IRSS) in Bobo-Dioulasso. They conducted a search that the scientists described as “humiliating and brutal.” It included sealing offices and laboratories and even inspecting the scientists’ vehicles for mosquitoes. A little later, on August 22, Burkina Faso’s Ministry of Higher Education, Research and Innovation issued a statement announcing the cessation of all activities under the Target Malaria project in the country. IRSS scientists destroyed the mosquitoes remaining in their insectary, and the government sent a team to spray insecticides in Souroukoudingan to kill the released insects. Many scientists, such as Fredros Okumu, a biologist from the University of Glasgow and the Ifakara Health Institute in Tanzania, consider the project’s halt a major setback in the fight against malaria. “This step is a real blow to the hopes for gene drives,” he said in an article in the Science magazine.

How scientists gradually progressed toward the practical use of gene drive technology

The essence of gene drive technology is to create a gene allele that will be passed from a modified individual to nearly all offspring — 99% or more — rather than the usual 50% in sexual reproduction. Thus, the changes persist in the population and spread through it over the course of several generations. The introduced gene can perform a specific function, for example, the individual may produce only male offspring. This makes sense for eradicating species of mosquitoes that carry malaria — that is, mosquitoes of the genus Anopheles, particularly Anopheles gambiae.

Ideas for implementing gene drives began to emerge in the early 2000s, and after the development of CRISPR-Cas9 technology (“genetic scissors”), progress accelerated. In 2018, scientists demonstrated the first functional gene drive capable of eradicating mosquito populations by targeting an exon of the doublesex gene, necessary for female development. Female individuals with two altered copies of the gene did not bite and did not lay eggs, becoming sterile. In 2020, the same group of researchers developed a sex-distorter gene drive (SDGD). It was based on a combination of CRISPR-Cas9 and X-shredder technologies — inheritance of a nuclease enzyme that destroys X chromosomes during spermatogenesis. As a result, only Y chromosomes could be present in the germ cells, and all insect offspring should be male. In experiments, this allowed for faster population collapse. Currently, Target Malaria researchers continue to investigate both approaches.

Technologies for reducing mosquito populations are used and studied not only in Africa. In the US, since the 1960s, the Sterile Insect Technique (SIT) has been successfully tested against several mosquito species. It is now being used against Aedes aegypti — carriers of yellow fever, dengue fever, and Zika virus. Males are irradiated to make them sterile and then released into the wild. They mate with females, but no offspring hatch from the resulting eggs. Most female mosquitoes mate with males only once in their lives, so the insect population temporarily drops significantly. The technique is also applied in Europe, for example in Italy. It has also been successfully used against other pest insects since the 1950s, particularly screwworm flies, and the method was first proposed by Russian geneticist Serebrovsky back in 1940. Over this time, SIT has proven its environmental safety.

There are also successful experiments with genetically modified insects. For example, to combat the same Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, genetically modified males carrying a self-limiting gene are used. Female offspring of such mosquitoes die at the larval stage due to developmental disruptions. About a billion individuals have already been released worldwide, including several million in the US, on the Florida Keys islands. This approach also helps reduce harmful mosquito populations by 95%. The difference from gene drive is that the altered genes do not spread to the entire population, meaning there cannot be a replacement of all mosquitoes with modified ones. Males carrying an altered copy of the gene, inherited from a modified father, pass it on to roughly half of their offspring, and over time, the “artificial” genes disappear from the population.

At the same time, gene drives can also be “tuned” to disappear over time — such technologies are now being considered for eradicating invasive animal species in New Zealand. And Target Malaria researchers chose a cautious phased approach, not jumping straight to deploying gene drive insects, to assess all risks. The project began with releasing sterile and GM mosquitoes while monitoring results, and if successful, it was supposed to culminate in releasing males with gene drives only after several years, had it not been stopped.

The Target Malaria project is aimed at reducing the population of malaria-carrying mosquitoes in sub-Saharan African countries. Each year, about 600,000 people die from malaria, with 95% on the African continent. Gene drive technologies could potentially put an end to the spread of malaria once and for all by completely eradicating the vectors. Vaccines against this disease are still in development, and combating mosquitoes by other means often fails, for example because they can develop resistance to chemical agents. That is why scientists around the world are seeking effective ways to defeat this disease.

In July 2019, Target Malaria researchers released several thousand male mosquitoes genetically modified for sterility. It turned out that they died earlier than unmodified ones. The August 2025 release was the second step. This time, the male mosquitoes carried a gene encoding an enzyme that cleaves the X chromosome in germ cells during spermatogenesis. This mosquito is genetically modified to produce predominantly male offspring (approximately 95% in the laboratory) and does not carry the gene drive technology.

The next step was supposed to be the release of mosquitoes with gene drives. The specific timeline for that transition remained unknown. Colonies of mosquitoes carrying gene drives are still being studied in project laboratories in the UK, Italy, and the US.

After obtaining results from the second release, completing further studies, regulatory reviews, and other steps, the insects could have been released in Burkina Faso — likely in a few years. However, shutting down the project after the second phase made its completion impossible. Now the technology’s development has been set back by several years.

The project was shut down despite the fact that as recently as March 2024, Burkina Faso’s Minister of Higher Education, Research and Innovation, Adjima Thiombiano, visited IRSS and expressed support for the project; it also had received approval from all regulatory bodies. The Target Malaria press office declined to comment on the situation for T-invariant but emphasized that the phased plan implemented by the project complied with all safety recommendations from several expert groups, including the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Guidance framework for testing of genetically modified mosquitoes from 2021 and others.

How Russian disinformation may have influenced the shutdown of the Target Malaria project

In 2014, Burkina Faso ended the 27-year authoritarian rule of Blaise Compaoré, who came to power after a military coup in 1987. At that time, the country underwent significant political reforms. Until recently, the organization Reporters Without Borders described Burkina Faso as “one of Africa’s success stories when it comes to press freedom.”

But in 2022, the regime in the country changed again. Power was seized in a coup by the military led by Ibrahim Traoré. Traoré — the second and current leader after the overthrow of Compaoré’s regime — suspended the country’s constitution and introduced a Transitional Charter that cannot be revised without his approval. The foundation of his ideological platform is revolutionary nationalism, the fight against France’s colonial legacy, and the country’s self-determination relying on internal resources. This fits well with rejecting cooperation with Western countries and shutting down projects funded from the US or Europe that are seen as undermining sovereignty. Regarding science and technology, Burkina Faso officials have asserted that the country needs “safer alternatives developed locally,” not experimental technologies imposed from abroad.

Up-to-date videos on science during wartime, interviews, podcasts, and streams with prominent scientists — subscribe to the T-invariant YouTube channel!

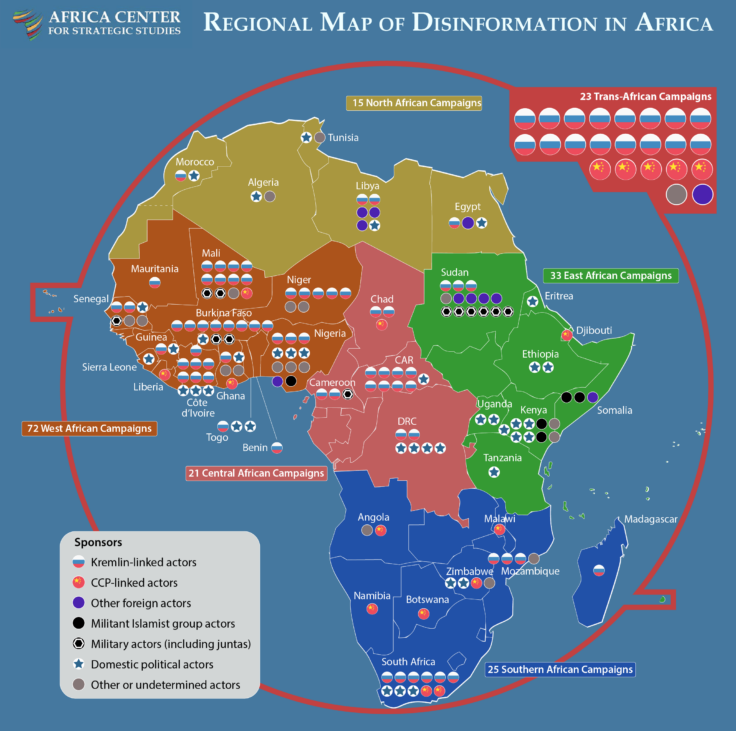

Joseph Siegle, Director of Research at the Africa Center for Strategic Studies, funded by the US Department of Defense, told T-invariant that it is not exactly known how decisions are made under the Traoré regime. However, the suspension of the Target Malaria project, in his view, follows the pattern of Russian disinformation aimed at discrediting Western public health initiatives in Africa. This includes earlier campaigns, such as spreading rumors about US biological weapons testing in Africa and creating doubts about vaccination efforts. Given Russia’s strong influence in Burkina Faso and the use of disinformation to support Traoré, it is reasonable, Siegle believes, to assume active involvement of Russian agents in the campaign against Target Malaria.

According to him, disinformation is a particularly prominent feature of Traoré’s governance strategy, a way for the government to exaggerate its purported achievements and maintain the appearance of popular support. The image created around Traoré and promoted with Russian backing is now spreading across West Africa and beyond.

According to data from the Africa Center for Strategic Studies, since 2022, Russia has sponsored 80 documented disinformation campaigns in 22 African countries — more than any other actor.

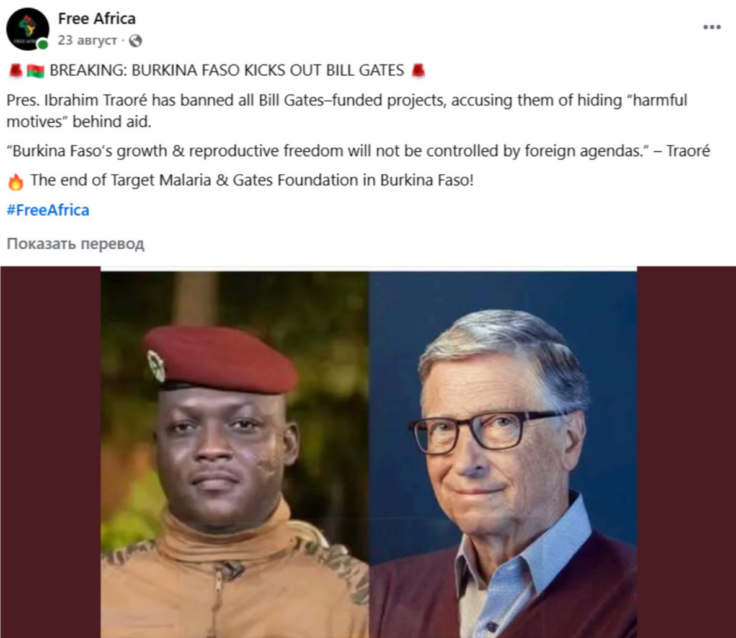

As early as 2024, an entire army of fake social media users falsely accused Target Malaria of spreading diseases and using mosquitoes as biological weapons. At the same time, the same users posted pro-Russian content, as reported by Agence France-Presse. Facing an organized disinformation campaign, project representatives were forced to respond, calling the attacks “false” and “deeply regrettable.”

Many experts believe that a major role in the Russian disinformation campaign was played by the “African Initiative” — an information agency closely linked to the late head of the Wagner PMC, Yevgeny Prigozhin, who created a secret network of mercenaries and disinformation spreaders in Africa. At the same time, the agency criticizes Western initiatives only indirectly. For example, articles criticizing Gates-funded projects were published mainly in Russian.

However, in 2024, the Global Engagement Center — a US State Department unit dealing with countering disinformation — published a report titled “The Kremlin’s Efforts to Spread Deadly Disinformation in Africa.” It exposed a network operated by Russian intelligence services through the “African Initiative.” Harmful health-related disinformation was spread through African journalists, bloggers, and local public figures.

According to the report, the agency used them to support and expand the organization’s work in bolstering Russia’s image and discrediting other countries. At the same time, according to a report from the French service for protection against foreign digital interference VIGINUM, the influence of this information agency should not be overestimated, as its main channels still have limited reach.

Nevertheless, on social media, one can find a large number of posts from African influencers who have long suspected Gates of attempting to use scientific projects as a cover for population control in Africa. American and European organizations are also accused of downplaying the risks of gene drives — for example, that the spread of GM mosquitoes will affect the environment — and conducting research solely for profit. In particular, to later sell technologies for combating insects, just as other foreign companies previously sold GMO seeds. Thus, in Kenya, cotton seeds from the company Mahyco were initially distributed free of charge. Usually, farmers can obtain planting material once and then take mature seeds from grown plants. But with GM plants, this doesn’t work: their seeds cannot be planted; new ones must be purchased from the producer each year at a high price.

In addition, there are whole networks of groups on Facebook that post and repost content of roughly the same nature criticizing Western countries or supporting Russia.

One well-known blogger with anti-Western and pro-Russian sentiments, Egountchi Behanzin, who has visited Russia repeatedly, frequently posts criticism of research funded by Bill Gates and similar projects. He denies having received funding from Russian organizations or participating in Russia’s disinformation campaign in Africa. However, he calls Russia’s policy in Africa “very good” and writes that African countries “must end any cooperation with the West.”

Behanzin has spread false information more than once. For example, in 2024, he accused the US of a new disease outbreak in Congo: “Is it a coincidence that the Congo has become an experimental laboratory where populations have become guinea pigs to allow the World Health Organization, the #BillGates foundation, Western pharmaceutical firms and American biolabs to test viruses and other dirty things?” He was also previously exposed by The New York Times, BBC, and The Wall Street Journal as a spreader of disinformation about malaria vaccines in Africa.

In a 2024 report by AIRA — the WHO’s Alliance for Infodemic Response in Africa, it is also noted that Russia participated in documented disinformation campaigns aimed at fostering distrust in Western health initiatives. These efforts include engaging local African political figures and influencers to shape false narratives. In Burkina Faso, a difficult situation has developed, including economic problems: the country faces poverty and violence, and Russia has effectively exploited opportunities to manipulate citizen discontent.

Russian disinformation operations in West Africa have led to a rise in public support for Russia, citizen demands for Russian intervention, and, in some cases, new military partnerships between African countries and the Russian Federation. Pro-Russian news agencies hold a significant place in national news in West and Central African countries, where military juntas have strengthened cooperation with the Kremlin and suppressed independent journalists. Some of these countries, including Burkina Faso, have also suspended the operations of Western media such as Radio France Internationale, Voice of America, and BBC.

Why anti-Western disinformation spreads easily in Africa

Russian disinformation falls on fertile ground. It manipulates the legitimate discontent of Burkina Faso’s population, blaming France for the country’s problems, portraying Russia as a savior, and supporting authoritarian leaders like Traoré who are willing to cooperate.

However, Russia is not the only country seeking to influence public opinion in Africa. According to historical data, the US and some European countries have a long tradition of such operations, both official and covert. During and after the Cold War, the continent became an arena of superpower rivalry, with the US often supporting any anti-communist regimes, ignoring democratic principles. Such policies are now considered a strategic miscalculation, but they left instability in some regions of the continent. Relations between France and African countries, particularly Burkina Faso, are also currently under reevaluation, as they typically did not benefit the people of the continent.

Currently, rejection of Western initiatives in Africa is linked to anti-colonial sentiments prevalent in African society, strict anti-immigration policies in Europe, and, more recently, in the United States as well, with both justified and unjustified fears of new technologies, which are also partly tied to past experiences.

Previously, colonial powers conducted medical campaigns that were not always successful against sleeping sickness, syphilis, and other diseases, which could have undermined public trust. The creation of medical services in the region was accompanied by research programs that did not always adhere to ethical standards.

In more recent times, clinical trials funded by the US were often aimed at solving problems more relevant to Western countries than to the people living on the continent, which also does not contribute to their popularity. Partly for these reasons, fewer medical studies are still conducted in Africa than in other regions of the world. Past failures still serve as a basis for spreading rumors that medical and other interventions by foreign doctors and researchers are unsafe. There have also been failed experiments with genetic technologies in Africa, for example, an experiment with genetically modified cotton conducted in Burkina Faso several years ago. According to some farmers, it led to reduced quality and increased costs, and eventually GMO seeds were abandoned in favor of conventional ones.

There are also many nonprofit civic initiatives in Burkina Faso that, for various reasons, do not support projects involving genetic technologies. These include local organizations and branches of European ones, such as the German Save Our Seeds, which calls for a global ban on releasing gene drives into the environment as part of the Stop Gene Drives campaign. Among its members are well-known eco-activists, such as Franziska Achterberg, who previously participated in Greenpeace campaigns and now works on biodiversity issues in the European Parliament.

One prominent African activist is Ali Tapsoba, president of the NGO Terre à Vie, an agroecological association fighting for food sovereignty and against genetically modified organisms. He has opposed the Target Malaria project virtually since its inception, believing that under the pretext of fighting malaria in Burkina Faso, researchers have organized an “open-air laboratory where the population serves as guinea pigs.” In his speeches, he calls gene drive technology highly controversial, unpredictable, and raising ethical concerns. In particular, the impact of gene drive organisms on health and ecosystems, in his view, remains unknown and potentially irreversible — although in the case of malaria mosquitoes, the inevitable population reduction poses no major risks because of its targeted impact on only three species (Anopheles ganbiae, An. arabiensis and An. coluzzi) out of more than over 600 species of mosquitoes recorded in Africa. He and his supporters also emphasize that the modified mosquito strains were created in European laboratories, raising questions of scientific neocolonialism and external influence.

Ali Tapsoba, along with activist Miriam Mayet from another non-governmental organization — the African Centre for Biodiversity — spoke at the 2018 UN Convention on Biological Diversity meeting during debates on genetic technologies. They called for a moratorium on gene drives, which was first proposed at the same Convention’s meeting in 2016. This proposal was rejected both times it was proposed.

In addition, Tapsoba is also a member of the Coalition for Monitoring Biotechnological Activities in Burkina Faso (CVAB), which on August 11 — the day the second phase of the Target Malaria project began — publicly called for suspending the testing permit and demanded the publication of documents that served as the basis for decision-making. The coalition expressed concerns about environmental risks, ethical issues, and lack of transparency. This was likely the final push that led to the project’s shutdown — on August 18, judicial police arrived at IRSS. In the Science article, Tapsoba supports the project’s closure and says that “it has no future in Burkina Faso or in Africa, and that this will set a precedent for all other African countries.”

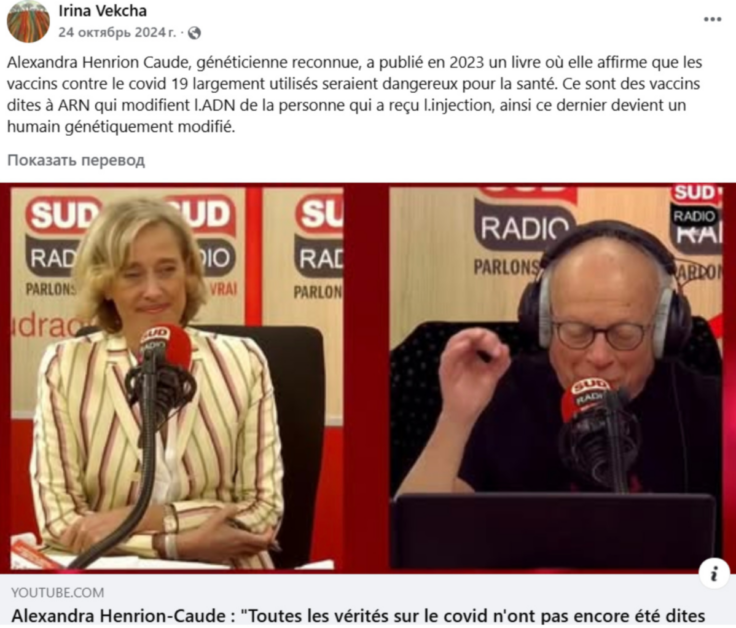

The scientific consultant for the NGO Terre à Vie is listed as a certain professor of genetics at ENSA — the University of Agricultural Sciences in Senegal — Irina Vekcha. Her Facebook account was created in April 2024. Almost all posts are dedicated to criticizing gene drives, GMOs, and projects funded by Bill Gates. Despite her status as a scientist, Vekcha also spreads clear disinformation, for example, about the supposed dangers of COVID-19 vaccines claiming they modify human DNA. She is also the author of numerous articles on the dangers of gene drives in non-governmental organization blogs. Attempts to contact her for comments were unsuccessful, and ENSA did not respond to the inquiry.

Some African non-governmental organizations are likely linked to Russian agencies. However, many NGOs act on their own initiative, fearing various risks or trying to protect local communities. At the same time, their statements can amplify false claims and are often used for disinformation purposes. For example, the influencer Bobo Dioulasso Afferage, who regularly post pro-Russian content, also shares narratives of such organizations on his social media. Moreover, their activities often align with Russia’s interests, for example, fighting GMO grains may lead to greater dependence on food supplies from Russia, thereby enhancing the country’s influence in the region.

Some scientists from Burkina Faso believe that the project’s closure may have been due to a href=”https://ges.research.ncsu.edu/2025/09/blog-governing-emerging-technologies-a-lesson-from-burkina-faso/”>poor communication on the part of Target Malaria. Project representatives conducted educational seminars, printed training brochures, and produced radio plays in local languages. They collaborated with Burkina Faso’s Ministries of Environment, Health, and Research, as well as regional and local authorities. However, they failed to find common ground with civil society representatives and to make their message understandable to a wider public.

Also, perhaps the researchers’ caution and the lengthy phased implementation of the project, which were necessary to reduce risks, might have reinforced public fears about its safety.

In the story of the Target Malaria project, it must also be considered that there is no consensus on gene drive technology even among scientists. For example, at the end of October 2025, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) congress was held in Abu Dhabi. The congress’s decisions have no legal force, but lawmakers in many countries take them into account. Among other things, they debated a moratorium on releasing genetically modified organisms into the wild. Before that, about 240 scientists and researchers signed an open letter opposing such a ban, while more than 80 signed in favor. The latter believe that the introduction of modified organisms is developing faster than safety and risk assessments. The former are convinced that a moratorium will slow down critically important initiatives, including those for combating malaria and invasive species. They believe it is wiser to assess the risks of each specific project rather than ban everything at once. In the end, the moratorium was not approved, but an amendment to IUCN policy was adopted, calling for additional precautionary measures when releasing GMO organisms into nature. Discussion and evaluation of innovative solutions is the norm for science, but this too can serve as fertile ground for disinformation messages and heightened fears.

In the opinion of PhD Joseph Siegle, disinformation exploits a wide range of emotional issues or grievances, which can then be supplemented with lies and distortions to evoke doubt, fear, and resentment toward the chosen enemy. To counter this, scientists and other experts must not allow an information vacuum to arise that can be exploited for malicious purposes. Instead, they need to regularly — proactively and promptly — disseminate fact-based stories that can promote critical thinking about lies and debunk these myths. Citizens of any country do not want to be manipulated and seek factual information. The more it comes from reliable sources, the less effective disinformation campaigns will be.