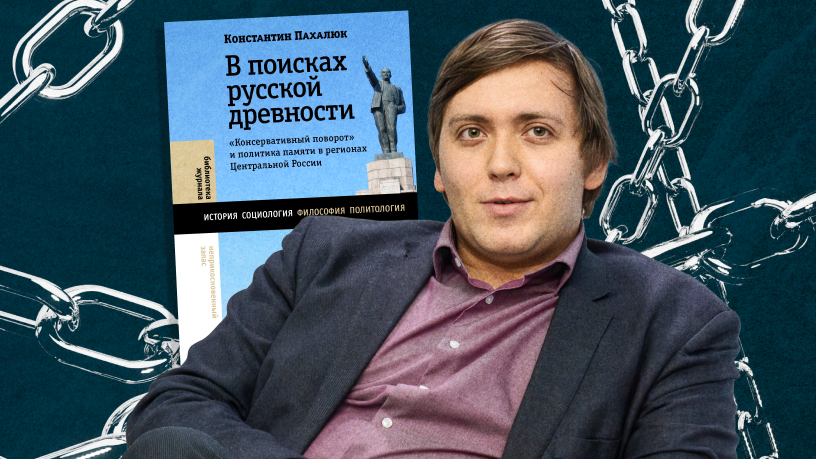

The latest censorship scandal in Russia involves historian and political scientist Konstantin Pakhalyuk’s book “In Search of Russian Antiquity”, which was removed from the website of the publishing house “Novoye Literaturnoye Obozreniye” following a complaint by the Orthodox activist group “Sorok Sorokov”. The group accused Pakhalyuk of criticizing the Soviet Army in his social media posts, alleging he had accused it of violence against civilians and liberated concentration camp prisoners. Shortly before this, T-invariant spoke with Pakhalyuk about the most significant shifts in the historical memory of World War II. Even before the invasion of Ukraine, claims that the West was downplaying the USSR’s role in defeating fascism had been increasingly pushed into public discourse. This eventually led to a large-scale campaign to enshrine the memory of the so-called “genocide of the Soviet people.” But why can’t any act of violence be labeled genocide? And who is behind the construction of this term?

Konstantin Pakahlyuk (b. 1991, Kaliningrad) holds a PhD from MGIMO (2020), where he defended a dissertation on “Discursive Foundations of Historical Interpretation in the Context of Modern Russian Domestic and Foreign Policy”. His research focuses on memory politics, including the Holocaust and Nazi crimes. He currently studies Israeli foreign policy and Russian “Z-militarism.” A columnist for several Russian-language outlets, Pakahlyuk was labeled a “foreign agent” by the Russian Ministry of Justice in 2024.

T-invariant: What’s wrong with the term “genocide of the Soviet people”? And who exactly is meant by “Soviet people”—all citizens of the USSR?

Konstantin Pakhalyuk: Soviet rhetoric framed it as “Everyone suffered, including our allies, but we suffered the most.” Today, the Russian government says: “The entire Soviet people suffered—though Slavs most of all” (which, incidentally, partly echoes Stalin-era rhetoric).

We must clearly define genocide, because the term is losing its meaning. Legally, it’s codified in the 1948 UN Convention: genocide is the intentional destruction, in whole or in part, of a racial, ethnic, religious, or national group as such. Essentially, it targets a people’s defining traits. The Convention lists qualifying acts—no written plan is required, just intent and implementation. Crucially, what often gets lost in Russian discourse is that victims are targeted not as enemies (for political/economic reasons) but solely for group belonging.

This definition makes accusations difficult—which, for historians, is a good thing. Clear criteria help distinguish between different phenomena.

When this narrative gained traction, pundit Egor Yakovlev (director of the “Digital History” project) quickly capitalized on it. Known for organizing exhibitions and publishing popular history books, Yakovlev—according to sources in publishing—was eager to release a lucrative book on the topic.

In 2021, his dream, so to speak, came true: he rewrote one of his own books on Nazism (incidentally, a fairly substantive work for its time) to align with the concept of the “genocide of the Soviet people.” The new edition, titled “The War of Annihilation”, was released at the end of 2021 and became a bestseller—the only one of its kind. The project received backing from the Russian Historical Society.

What exactly did Yakovlev do? It’s unclear whether he fully reflected on the implications himself, but his argument went as follows: the topic of genocide is currently fashionable in the West, where various forms of colonial violence are increasingly recognized as genocidal acts. He then asserts that Hitler, too, viewed the Soviet Union as a potential colony—and thus, the atrocities committed could likewise be classified as genocide. While no one disputes the colonial ambitions of the Third Reich, there are nuances to consider.

Yakovlev’s key piece of evidence is the so-called “Hunger Plan” (or “Backe Plan”). Herbert Backe, State Secretary of the Reich Ministry of Food and Agriculture, proposed in 1941 that Germany’s food shortages and war effort be sustained by exploiting the USSR, where there was allegedly a “surplus population.” He estimated this “surplus” at around 30 million people, who were effectively condemned to starvation.

Could this plan be described as genocidal? Certainly. However, it was never fully implemented—the Battle of Moscow rendered it obsolete. A more accurate term for what transpired would be a humanitarian catastrophe. Yet Yakovlev’s narrative simplifies the matter: since so many people died, he concludes, it must have been genocide.

But that’s not all. Yakovlev attributes every failure of Stalin’s government to genocide as well. The famine in Arkhangelsk, the starvation in Siberia in 1942—all were framed as acts of genocide against the Soviet people by the Nazis. In short, Yakovlev’s handling of facts—especially given that he is not a professional historian and had never taught at a university at the time—is highly questionable. His work relies on reinterpretations of existing sources and attempts to pass off well-documented facts as some sort of “scientific discovery.” Both I and historian Ilya Altman have criticized this book.

When Yakovlev cites, for example, the “Hunger Plan” and its policy of “eliminating surplus mouths to feed,” he emphasizes its economic rationale—which does not meet the legal definition of genocide. Similarly, when Alfred Rosenberg, head of the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories, declared that the Wehrmacht must ensure Russians could never rebuild their statehood, this was primarily a political objective. However, a closer examination of Backe’s plans in the summer of 1941 reveals that his starvation policy was explicitly directed at Russians. Even Hitler’s ambition to “erase Leningrad and Moscow from the face of the earth” was rooted in preventing Russians—in the Nazi imagination—from ever restoring their nation. This critical link between extermination policies and ethnic targeting of Russians is, notably, overlooked by Yakovlev.

All of this falls under a term established after the Nuremberg Trials: “crimes against humanity” (or “crimes against humaneness” in some translations). There is a crucial distinction between the two. “Crimes against humanity refer primarily to systematic violence targeting individuals as victims, whereas “genocide” pertains to the intentional destruction of specific groups.

Of course, debates persist: Can racial or ethnic violence be classified as genocide? In my view, the term is overused today. Armenians invoke it regarding events in Karabakh; Palestinians have accused Israel of genocide, while Israelis labeled the October 7 attacks as genocidal. This reflects the term’s politicization—most global conflicts remain interethnic, and the label often serves as a rhetorical weapon.

The massacre of Jews at Babyn Yar was unequivocally genocide, part of the Holocaust, which we universally recognize as such. The entire Yugoslav Wars do not qualify, but the slaughter of over 8,000 Bosniaks in Srebrenica does. Similarly, Nazi occupation policies prioritized Jews as the primary victims. The systematic murder of Roma also meets the criteria for genocide. Other forms of violence, however widespread, are more accurately termed “war crimes” or “crimes against humanity”. The phrase “war of annihilation” captures this reality far better.

Invoking “genocide” demands clarity: “Genocide of whom?” One must prove that Nazi Germany sought to eradicate a unified “Soviet people” solely for their collective identity—a claim that collapses under scrutiny. Breaking down the USSR’s ethnic composition reveals no comparable policy toward Russians, Belarusians, Ukrainians, or Baltic peoples. *Racial and ethnic violence* is a more precise descriptor for Nazi occupation policies. Definitions matter not as a hierarchy of suffering, but as tools for precision.

If every act of racial violence is labeled genocide, we risk erasing the specificity of events like the Armenian Genocide (1915), the Holocaust, Rwanda, or Darfur—lumping them together with broader atrocities. This blurring makes it harder to identify, prevent, and study genuine genocides. The term must retain its sharp edges, lest it lose all meaning.

T-i: So would it be more accurate to call these either war crimes or crimes against humanity?

KP: Yes, primarily crimes against humanity. Terms like “terror” or “policies of extermination” would also apply. Theoretically, some individual atrocities could potentially be classified as genocidal acts against Russians, Belarusians, or other occupied peoples—but this hasn’t been substantiated by research, and I can’t cite any such cases offhand. I don’t rule out that future studies might revisit this, but the core issue is that the current “genocide of the Soviet people” debate isn’t about scholarly precision. It’s not the academic discussion it should be. This discourse exists solely for ideological purposes—to position “us” as the ultimate victims. From there, the arguments are cherry-picked, and the debate becomes meaningless. We’re constrained by facts; they’re constrained only by their imagination. How do you argue with people who dismiss every counterpoint with, “This is our framework—are you blaming the victim?”

T-i: Are there similar cases of “genocide construction” in other countries?

KP: The search—or invention—of genocides is widespread. In the 1990s and 2000s, for instance, there was a push to frame atrocities as the genocide of the Polish people.Serbs, Albanians, Greeks, Palestinians, and groups in India have all claimed their own genocides. These narratives feed into national myths, but the problem is that the term “genocide” gets diluted into a synonym for “mass killings”. Over time, these claims should face scholarly scrutiny—but in Russia, researchers invoking the UN Genocide Convention often do so superficially, without engaging with the academic literature. So we end up with a “genocide of the Soviet people” simply because someone wills it into existence.

T-i: How did this term enter the discourse, and what problems does it raise?

KP: From a scholarly standpoint, the “genocide of the Soviet people” has no basis in historiography. The state pressures academics to adopt this terminology: “You will interpret events exactly as we dictate”. Politically, the motive is transparent. By the early 2020s, the Kremlin realized that Western audiences had little interest in hearing about the Red Army’s liberating mission. So they pivoted to “genocide of the Soviet people”—a way to assert, “We were the war’s primary victors” and “its primary victims”.

There was initially some internal debate about how to square this with the Holocaust, but after 2022, that discussion likely ended. The war also triggered broader debates about guilt and responsibility—including in opposition circles—which the regime closely monitored. Since these discussions drew parallels to WWII and the Holocaust, they were purged from public discourse. Any nuanced reckoning with the USSR’s role, any “Western-style” reflection on culpability, vanished. All that remains is the “genocide of the Soviet people” and its core message: “We suffered most”. It’s pragmatic—and it weaponizes history for politics.

Several factors made this line of argument possible. First, there’s the widespread tendency—even among scholars—to conflate “genocide” with “mass violence” broadly. Some historians of Nazi crimes themselves have used the term loosely, diluting its legal and conceptual precision. Second, the strategy of memory-policy actors in the 2010s played a role. Ironically, a major catalyst was the rise of “Russia’s Search Movement”. Launched in 2013 under the auspices of the Presidential Administration, it consolidated most independent search teams under state oversight.

On the surface, its mission is noble: locating and reburying WWII soldiers and connecting with their families. But the movement’s leadership—notably State Duma deputy Elena Tsunaeva (since 2021, First Deputy Chair of the Committee on Labor, Social Policy, and Veterans’ Affairs)—ties it closely to the state. Over time, this “scaling up” took on a political dimension.

By 2017, the Search Movement began excavating civilian burial sites under the pretext that these were “victims of genocide,” thus justifying funding and access. The catch? Russian law only permits such exhumations for military graves. No legal changes were made—until June 2024, when a draft bill “On Immortalizing the Memory of Victims of the Genocide of the Soviet People” was submitted to the Duma. Its explanatory note tacitly admits the illegality: “Current practices of exhuming civilian remains under the ‘genocide’ framework lack legal authorization, potentially exposing search teams to criminal liability (e.g., under Article 244 of the Criminal Code: ‘Desecration of Bodies and Burial Sites’).” In short, these digs are “literally unlawful”—yet state-backed.

Another key player is Alexander Dyukov‘s “Historical Memory” Foundation. Dyukov, author of “The Myth of Genocide: Repressions by Soviet Authorities in Estonia (1940-1953)” – which denies ethnic-based repressions – has in other articles dismissed the Soviet occupation as a myth. The foundation was established around 2008, when Dyukov began actively giving lectures and organizing exhibitions.

During this period, they published an aptly titled collection “The Great Slandered War-2: We Have Nothing to Apologize For!”. The foundation’s work, like Dyukov’s own efforts, primarily targeted the Baltic states, Ukraine and Moldova – recruiting scholars to participate in this “memory war,” producing material about collaborators from these countries, their involvement in the Holocaust, and denying Soviet repressions. Essentially pushing narratives like “look how they glorify Bandera supporters,” but packaged as academic research. By the mid-2010s, they expanded cooperation with Belarusian authorities, producing articles about Kalinowski.

Yes, they raised sharp and important issues—but in a propagandistic manner rather than as genuine researchers. At the same time, they worked with real documents, and even Dukov himself believed that the Katyn massacre was the work of the NKVD, meaning they had the potential to produce truly significant academic work. However, the only tangible contribution from this foundation was translated literature—such as works by sociologist Michael Mann—or a series of document collections on Katyn or the Nazi punitive operation “Winter Magic.” This should not be dismissed. Behind the scenes, employees of “Historical Memory” even took pride in engaging in what they called “smart propaganda”—that is, in their view, combining scholarship with the promotion of “desirable” theses, something academic historians often failed to notice.

The foundation began pushing the narrative of the “genocide of the Soviet people” in the late 2010s, following a leadership change in the Presidential Administration, when it became necessary to demonstrate their usefulness. Riding the wave of accusations against Western countries, they developed this theme—for instance, compiling a list of living Latvians who had once been SS members and declaring them “unfinished business.” They also revisited the siege of Leningrad: if it was a crime against humanity involving Europeans alongside Germans, who exactly was complicit, and what was their guilt? Moreover, the foundation closely monitored how, in the mid-2010s, Lithuania convicted participants in operations against the “Forest Brothers” as accomplices in genocide. This, too, likely had an impact: if “we” are being accused of genocide, why not retaliate?

Additionally, this was a kind of “response” to the European Parliament, which adopted the ”Resolution on the Importance of European Remembrance for the Future of Europe” in 2019. The resolution framed World War II as a consequence, in part, of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and condemned the pact itself. In response, the Russian Foreign Ministry denounced the resolution as “historical falsification.” Putin publicly criticized its adoption on three separate occasions and escalated tensions with Poland, accusing it of instigating World War II. As one high-ranking Presidential Administration official (at the level of a department director) later explained to me: “Europe criticizes us for complicity in starting World War II. But no one criticizes the Jews—because they are victims of the Holocaust. That’s why we must position ourselves as the primary victims.”

In short, the political climate was favorable for the Foundation: the topic was in demand, and the stance of “we are guilty of nothing, we are the victims” was being pushed at the state level. Elena Malysheva (then dean of the Archival Studies faculty at RSUH) was brought in as deputy director to oversee the project. The Investigative Committee also got involved, publishing reports on the discovery of mass graves of civilians. Furthermore, efforts were made to identify perpetrators, and new trials were launched in 2020–2021 (with the Russian Military-Historical Society actively covering the proceedings—ed.). These trials took place in Novgorod, Pskov, and elsewhere—with Dukov later making his own appearances.

Now, all that remained was a small step: to issue a directive to the media that any topic related to Nazi crimes would henceforth be labeled as “genocide.” No matter what had actually occurred—it was now the “genocide of the Soviet people.” Denying this was branded as “rehabilitation of Nazism” and a rejection of the USSR’s role, as outlined in the widely circulated RT article “Every Fifth”, published on the anniversary of the liberation of Rzhev. Moreover, new criteria for genocide were proposed, since the UN definition (where, according to this narrative, Europeans deliberately downplayed the USSR’s role) was deemed unsuitable.

By 2022, the genocide narrative was repurposed to draw historical parallels: “Back then, it was the genocide of the Soviet people; today, it’s the genocide of Russians. And we, supposedly, are saving these Russians from genocide.” Since then, the theme has evolved further, sparking debates over who should be included in the list of victims—and who should not. For Yakovlev, the primary victims were Jews, Roma, and Slavs—the latter category encompassing Russians above all, though he also mentions Belarusians, Ukrainians, and, I believe, Poles. Dukov, however, disagrees: he does not consider Ukrainians victims. This is where the discourse spirals into pure abstraction.

Notably, Yakovlev’s book has already gone through four editions, each with revisions. Observe the evolution of its titles: initially, he wrote about a war of annihilation, then shifted to “genocide of the Soviet people,” by 2023 to “genocide of Soviet peoples,” and by late 2024 to “the destruction of Slavs.” The substance remains roughly the same, yet the target of genocide changes three times. Shouldn’t they at least settle on one version first?

T-i: So, with the start of the war, did the rhetoric blaming specific nations for Nazi crimes intensify?

KP: Absolutely. On one hand, the narrative of “we are the primary victims, and no questions should be asked of us” continued. Then came the addition of Russian nationalism: “But Russians suffered especially”—along with reminders of the “genocide of Russians” and claims that they are still targeted for destruction. The Ukrainian angle takes this to absurdity. In 2023, during a meeting with Alexander Shkolnik, director of the Central Museum of the Great Patriotic War, Putin declared that “1.5 million Jews were killed by Bandera supporters and their ilk.” Shkolnik was so stunned he even tried to object, but was promptly schooled in the “true history” he was now expected to uphold. This is mythmaking at its core—a game of victimhood. The message is: “We were victims then, and we are victims now. The whole world treats us poorly; Russophobia is rampant, we are unloved.” And this emotional pressure keeps escalating.

T-i: The “No Statute of Limitations” exhibitions cite precise figures, down to the number of people killed. Are these truly archival records, as claimed by the organizers, and how reliable are they?

KP: Back in 1942, the “State Commission for the Investigation of Nazi Atrocities” was established. Its purpose was to document Nazi crimes in liberated territories: collecting reports, compiling evidence, and consolidating it into a unified record. Why? To later demand reparations after victory—”Now pay for all this.” Local commissions conducted partial exhumations, drafted protocols, and interviewed witnesses. These documents were then aggregated at the republican and all-Union levels. However, the data from local commissions often conflicted with the centralized summaries.

When a commission arrived in a burned village, it didn’t ask: “What actually happened here? When? Was this a Nazi massacre of locals? Or a partisan “cleansing” operation with forced evacuations? Or did the village burn during combat? Was it entirely destroyed, or just a few houses?” The sources provide no answers—just a raw count of destroyed settlements in a given region.

A. I. Golyshev’s “Chronicle of Burned Villages in Pskov Region” lists these villages, but the author often couldn’t even pinpoint their exact locations from archival records. “A village existed, then burned. That’s it.” Finding the data is one thing; reconstructing the chain of events is another. Similar large-scale research exists for Belarus, but it, too, is riddled with gaps—this is painstaking, complex work.

The same applies to population figures. Commission reports include data on those forcibly sent to labor camps (“Ostarbeiter”), but omit those who “chose” to leave with the Germans. Half a million people emigrated this way, settling in Germany or elsewhere—a major wave of displacement. Yet in official records, they were uniformly labeled as “forcibly deported,” with no acknowledgment of their refusal to live under Soviet rule.

T-i: So, this is an ideological construct based on documents with an ideological bias that haven’t been properly studied?

KP: It’s an ideological construct built on a selective set of sources that are accepted uncritically. A historian cannot—and must not—simply paraphrase archival documents. A historian who does that is an idiot. A researcher analyzes sources within a specific framework, for specific purposes, and only after source criticism can they extract, quote, or highlight anything. Any document citation is usually just an illustration—it’s never proof on its own. In proper historical research, you first define your question and methodology, then turn to sources to see what they reveal about the topic. People unfamiliar with historical scholarship don’t grasp this because they assume truth is whatever lies in the archives. And that’s how myths are born.

T-i: How does this square with the myth that “all history has been rewritten”? On one hand, archives supposedly contain unassailable truth requiring no critique, yet on the other, history is dismissed as falsified. Is there no logic here—just emotional manipulation?

KP: Historians study sources, cross-reference them, and interpret them—often making mistakes and correcting them. It’s a collective debate. Research on Nazi crimes, including in occupied RSFSR territories, has evolved over decades and continues to do so. Even projects like “No Statute of Limitations” have done important work digitizing archives (both federal and regional). But synthesizing this requires time, German sources, historiography, and more. It’s a slow process. The term “genocide of the Soviet people” is utterly irrelevant here—it explains nothing.

Then there’s the opportunism. Some historians noticed funding flowing toward this narrative: grants for anthologies, conferences. Suddenly, slapping “genocide” on your work became a career move. Take Nikita Lomagin, a brilliant blockade scholar from the European University, who became scientific director of the Museum of the Defense and Siege of Leningrad in late 2021. He was given a department but no real budget. So he played along—*Fine, let the siege be “genocide.” Then, in 2022, the EU came under pressure. Even respected scholars bend when squeezed. In one interview, Lomagin started drawing parallels between WWII-era “genocide” and the current war against Ukraine, echoing Z-propaganda.

Others pay lip service. A recent dissertation in Rostov-on-Don on Nazi crimes in the region mentioned “genocide” once—in the introduction. The author didn’t need it for the research, just for bureaucratic compliance.

T-i: Like quoting Marx in Soviet dissertations for formality’s sake.

KP: Exactly. My stance—that we shouldn’t just accept state-imposed narratives—used to be easier to defend, especially before 2022. I know most Russian scholars specializing in Nazi occupation and crimes personally: they oppose this framing. They’ll play along superficially, but there’s no scholarship behind it. At a 2022 roundtable at RSUH with Ilya Altman, we invited Yakovlev and Dukov. Yakovlev (online) couldn’t answer basic questions—like why he linked racial violence to village burnings without evidence. Dukov dodged entirely, speaking about Nuremberg’s “genocide” debates—irrelevant to the “Soviet people” claim.

The keynote came from Vladimir Simindey, editor of the “Journal of Russian and East European Historical Studies”: “The ‘two totalitarianisms’ theory (equating USSR and Nazi Germany) is used against us. We need a counter-narrative.” Hence, “genocide of the Soviet people”—citing Michael Mann’s “politicide” (elite extermination). Nazis killed Party officials? Call it “genocide.” They replace one vague term with another, misrepresent sources, or outright lie. Backstage, Simindey admitted it’s all political theater: “Don’t take it seriously.”

T-i: Meanwhile, alternative views are erased from public discourse, and equating Hitler/Stalin is now illegal.

KP: Worse, people don’t even understand what counts as “equating.” Many now self-censor. Take the 2019 ban on Nazi symbols: it allowed academic/critical use, but publishers preemptively purged books on WWII. Even a German insignia resembling a swastika meant removal. Or the backlash against Alexander Ermakov’s “Wehrmacht vs. Jews: War of Annihilation”—accused of “glorifying Nazism” by detailing atrocities. The result? Scholars now just parrot “genocide” without scrutiny.

T-i: Is there any hope of reclaiming the term’s academic meaning?

KP: How? Russia’s authoritarian turn makes dissent impossible. Challenge “genocide of the Soviet people”, and you’re accused of “prioritizing Jewish victims over ours.” It’s moral panic, not debate.

In 2023, the National Center for Historical Memory was created under Malysheva, tasked with “protecting traditional Russian values and historical truth.” See how this plays out: the “No Statute of Limitations” project launched “Destroyed Childhood,” memorializing the 1942 massacre of 214 disabled children in Yeysk as “genocide of the Soviet people.” Soviet-era accounts called it a “crime against childhood.” Now, it’s framed as part of Nazi “disability extermination”—a policy that began in pre-1941 Germany (sterilizations, then gassings halted by public outrage). On occupied soil, such violence was sporadic, not systematic.

Calling this single atrocity “genocide” is cynical. These children had no future in the USSR either—state neglect of disabled orphans continues today. The Nazis were monsters, but cherry-picking incidents as “targeted childhood annihilation” is absurd.

T-i: A revival of Soviet memory practices?

KP: This is indeed a revival of Soviet practices in new forms.

Soviet ideology serves as a source of inspiration here. On one hand, the current regime needs to cultivate an image of itself as a victim, while on the other, it requires an enemy to blame. Every discussion of “we are the victims” inevitably comes with a search for culprits.

And here, there is ample room for mythmaking. Nazi occupation—particularly within the RSFSR—remains severely understudied. There is not a single comprehensive scholarly work examining Nazi policies toward Russians beyond memoirs—no systematic tally of burned villages, no compiled documentation of atrocities, nothing. The experience of children during the war is similarly neglected in academic research. They are simply “victims,” their numbers large enough to render further inquiry unnecessary. Even collaboration remains a marginal topic: in places like Smolensk, for instance, Russian policemen participated in the execution of Jews alongside Germans.

What emerges from this void? A vague notion of “mass and total crimes,” accepted as self-evident yet devoid of specifics. And it is this ambiguity that the authorities exploit.