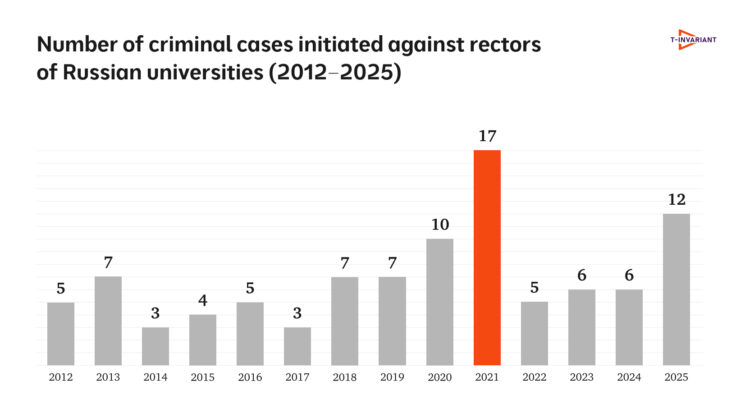

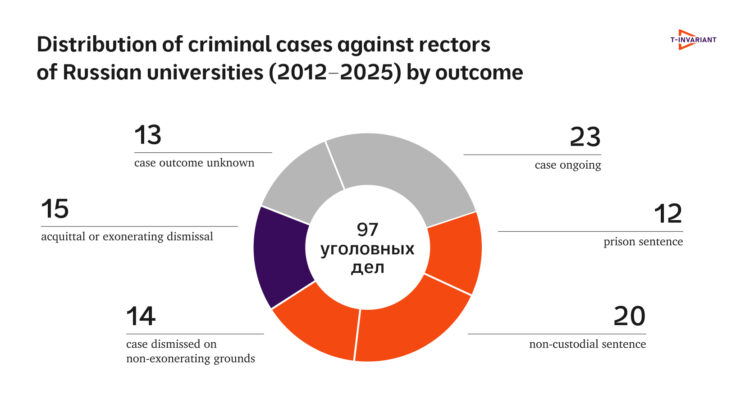

The year 2025 isn’t over yet, but we already know of 12 instances of criminal prosecutions against rectors of Russian universities, as well as 10 sentences handed down to them. And this isn’t a record: in the last pre-war year of 2021, law enforcement took interest in 17 university leaders. This is how the process of elite turnover is unfolding in higher education, which Vladimir Putin initiated after returning to the presidential seat in 2012. T-invariant examined the stories of criminal prosecutions of rectors from 2012 to 2025 and found that leading a university is no less dangerous than serving as a deputy to a governor or minister.

ALL ABOUT RECTOR-CRIMINALS.

VIEW THE TABLE.

“For the Crimes That Get You Shot, Graves are Dug up Fast.”*

Recently, the former rector of Kazan Federal University, Ilshat Gafurov, was found guilty of inciting the murder of Yelabuga deputy Aidar Israfilov. The 64-year-old Gafurov sentenced to 22 years in a strict-regime penal colony. But this is more of an exception: rectors are much more often accused of economic crimes.

According to Dmitry Zair-Bek, head of the human rights project “First Department” (a Russian NGO operating in exile, focused on defending those accused in political cases), the position of rector today inherently fraught with the risk of facing criminal charges. However, similar risks are faced by many heads of state institutions. Today, “execution-prone” status characterizes any high-level position in the public sector where large budgets come under intense government scrutiny, Zair-Bek noted in a conversation with T-invariant.

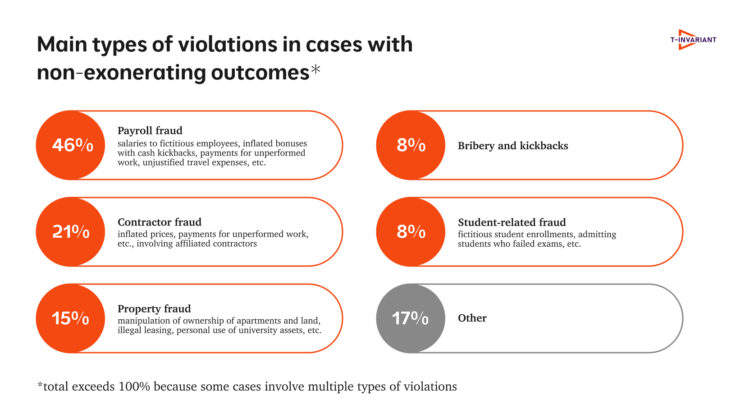

“Top managers in higher education handle substantial budgets, engage contractors, allocate grants, and some undoubtedly exploit their official positions for personal gain. Rectors come under law enforcement scrutiny in cases involving embezzlement of public funds, accepting bribes to facilitate admissions, or organizing kickback schemes with incentive payments. By the way, regular ‘criminal’ personnel rotations also occur in institutions of additional professional education. For instance, the rector of the Institute of Regional Development in Penza Region, Gennady Belorybkin, recently became a defendant in an embezzlement case, and the pro-rector of the Institute of Educational Development in Bashkortostan, Azat Yangirov, went to trial for taking bribes. The same happens in secondary vocational education institutions: the director of Samara Polytechnic College, Konstantin Voyakin, became a defendant in a fraud case, as did his colleague from Bashkortostan, the director of Duvan Multidisciplinary College, Talip Fazlaev, who will soon hear the verdict in a case involving fraud and bribery. Working with public funds creates a fertile ground for manipulations, so educational managers most often become defendants in ‘economic’ criminal cases, as well as crimes against state authority and public service interests,” says Dmitry Zair-Bek.

Top news on scientists’ work and experiences during the war, along with videos and infographics — subscribe to the T-invariant Telegram channel to stay updated.

The constant manual turnover of rectors allows for injecting “fresh blood” and appointing loyal allies to key positions, while preventing university leaders from turning into uncontrollable barons in their domains, notes Zair-Bek. “On the other hand, changing a rector is no less unpredictable than changing a governor. You never know when someone will be removed or appointed. This is a hallmark of Russia’s vertical power structure: people are in constant uncertainty, rewarded for loyalty, with eyes turned away from dubious stories, but at any moment they can be ousted and face criminal charges if something goes wrong or a new scheme emerges. This doesn’t mean all cases are initiated ‘for cause’ or, conversely, show signs of fabrication or political motivation: in each case, both factors intertwine in varying proportions. What’s important is that this practice puts the rector in an inherently vulnerable position, where even minor missteps or intrigues can mark the start of a career’s collapse,” believes the human rights defender.

However, being a rector is one of the most dangerous public positions in Russia not only in terms of criminal prosecution. Some university leaders didn’t live to see their verdicts and died during investigations, and they weren’t particularly old by Russian standards. In 2023, a criminal case was opened in Omsk against two leaders of the local state technical university. Rector Dmitry Maevsky got off with a suspended sentence a year later, while his predecessor in the post, Anatoly Kosykh, who was involved in the same case, died. He was 68 years old. In 2020, in Samara, law enforcement acted even more radically against three leaders of the local agricultural university. Ultimately, the criminal cases largely collapsed. One defendant, acting rector Igor Guzhin, received an official apology from the prosecutor (a rare event these days). The second, Sergei Mashkov, was under investigation for four years but has continued to lead the university to this day (despite a guilty verdict with a fine as punishment). And their predecessor, Alexander Petrov, died at the age of 53.

Anatoly Polyankin also died while under house arrest. The rector of the Higher School of Performing Arts was 70 years old. Polyankin was involved in a high-profile scandal surrounding the property and creative legacy of the Raikin family (renowned Soviet satirical artist Arkady Raikin and his son, Konstantin).

There may be more shattered lives: for many defendants, no information exists about their circumstances after the case began or the verdict was issued. In most criminal prosecutions, rectors effectively drop out of professional life, even if they manage to avoid real or suspended sentences. However, there are striking exceptions.

“I’m not old, but my hair’s gone gray — In this life, nothing takes me by surprise”

In the list of rectors, Viktor Efimov stands out — he led St. Petersburg State Agrarian University from 2005 to 2015. The first secretary of the District Committee of the CPSU (Communist Party of the Soviet Union) in the last Soviet years followed a winding path. Having worked in the 1990s as director of poultry and pasta factories, Efimov participated in creating and promoting the Concept of Public Security ‘Dead Water’. The book Dead Water was deemed extremist, students considered the scholar’s works sectarian nonsense, but they long occupied the university library shelves. Efimov attempted “from the standpoint of systemic knowledge of the Holy Russian priesthood to provide an understanding of the essence of schemes of global supranational control over Russia, implemented by conceptual power over the last thousand years.” The book also posits the existence of a world conspiracy (predictor) carried out more than three thousand years ago by ancient Egyptian priest-hierophants who control the “World Masonic Government.” Efimov was arrested in 2018 for embezzling university funds, sentenced in 2019 to five years in prison and a fine, but in 2021, he received a suspended sentence instead. Today, his VK community (a Russian social network similar to Facebook) has over 47,000 subscribers. So, the chances for “reproducing a healthy population across generations in harmony with Earth’s biosphere” still remain.

In some universities, criminal cases are opened quite regularly. Notably, Moscow State University of Food Production, now the Russian Biotechnological University (ROSBIOTECH), is among them. Both rectors who came under investigation have interesting biographies. Dmitry Edelev is the son of a deputy interior minister, Mikhail Balykhin is the son of a former first deputy minister of education and science. A case against Edelev was opened back in 2012, but no data on its outcome has appeared. When his careers as a surgeon, economist, rector, and deputy faded, Edelev found himself as an expert on deadly “chemicals” in food, as well as “living” and “dead” water. Additionally, Edelev is the scientific director of Arbat Clinic. And Balykhin in March 2025 received five years in prison for embezzling money allocated by the Ministry of Education and Science for developing a vaccine against sheep anaplasmosis.

The reason for the many cases where rectors come under investigation isn’t that they are part of some particularly corrupt group, nor that there’s a special hunt for them, believes sociologist of science Mikhail Sokolov.

“Investigative agencies at some point discovered that universities are rife with activities that could be classified as economic crimes,” he says. “They didn’t look in that direction before, but now, through trial and error, they’ve found that if you search, you can always find what you’re looking for, and they’ve begun targeting the Ministry of Education’s purview.

The most typical violation, judging by recent cases, is that rectors usually have a black cash fund from cashed-out bonuses or other employee payments. The fact that they have this fund is a paradoxical result of the fight against corruption. Due to current Russian legislation, any public organization is bound by so many restrictions that many operations — even the most innocuous — are a hundred times easier for the rector to handle through cashing out than through official accounting channels.

I remember how about 10 years ago, when Project 5-100 [a Russian government program to elevate select universities into global top-100 rankings — T-invariant] was in full bloom, we tried to use external grant funds to buy books on Amazon for a partner center in one state university. The grant was ours, the books were to stay in the university library. What could possibly be the catch? But the only legal way was to announce a tender, wait several weeks, and then either pay triple to an external contractor who would buy the books on the same Amazon, or not get them at all if no firm bothered with such a small job. I don’t remember how we got out of it, but I’m sure it fell under some article of the Criminal Code. The result of all these regulatory efforts is that now, not just rectors — nine out of ten leaders of a Russian Science Foundation grant have some small stash from grant funds for such cases. It’s scary to think what will happen if this idea reaches the investigators.”

“ Who’ll Forgive, Who’ll Understand, and Who’ll Weep for Me?”

Different rectors have varying outcomes in life after criminal prosecution and serving their sentences. The rector of Irkutsk National Research Technical University, Ivan Golovnykh, was acquitted after a four-year investigation, subsequently awarded the title of honorary professor, and has delivered a video address to graduates. He now participates in the university’s activities, and remains active in the Russian Academy of Sciences. Ivan Artyukhov from Krasnoyarsk State Medical University, after an acquittal, stated he would seek an apology from the prosecutor and go to the European Court of Human Rights. This isn’t quick (especially now), but in interviews with local TV channels, he shows his collection of household utensils, his family genealogy from the 17th century, and promises he’ll re-enter his university only as a full victor.

However, stopping the judicial machine isn’t always easy. The case of Tatiana Barkhatova, head of Kuban State Technological University in Krasnodar, has been ongoing for seven and a half years. Recently, the case was sent for retrial for the fourth time. The rector of North Ossetian State Medical Academy, Tamara Gatagonova, held her position for two out of the five years the investigation lasted. The first-instance trial went on for three years, with 56 hearings and continues in higher courts. Another record-holder from our list is Anatoly Aralov, rector of the private Essentuki Institute of Management, Business, and Law. In 2025, his criminal case for tax evasion became his tenth.

Up-to-date videos on science during wartime, interviews, podcasts, and streams with prominent scientists — subscribe to the T-invariant YouTube channel!

Some figures from our list seek an escape from criminal prosecution through occupied territories of Ukraine. The rector of Immanuel Kant Baltic Federal University, philosopher Alexander Fyodorov, became famous not only for the noisy celebration of the 300th anniversary of Immanuel Kant — but also for a photo where, during his arrest in his office, he faces a table piled with five-thousand-ruble notes — it became very popular. Fyodorov asked to be sent to the SVO (the official Russian term for the war in Ukraine), but instead of the front, he received charges in new episodes of the case.

In 2023, Georgy Grets, head of Smolensk State University of Sports, asked for the same, later sent to a strict-regime colony for 12 and a half years. So far, the Ministry of Defense hasn’t accommodated the rector. In 2025, their colleague from Ulyanovsk State Technical University, Nadezhda Yarushkina, proposed an original alternative: she asked to be assigned to drone development.

What does the intensification of repressions against rectors and university staff in general mean for higher education? Overall, the rector position is becoming less attractive, believes Mikhail Sokolov.

“A recent study found that the average salary of a top Russian rector is about 600,000 rubles (~$6000) per month. Seems like decent money, especially by Russian standards. But consider that a rector actually leads an organization with several hundred or thousand employees. The leadership tasks are extremely diverse: monitoring student nutrition, negotiating dormitory construction, handling financial reporting, ensuring publication growth, and establishing international cooperation. Moreover, the university contingent is usually demanding, sometimes even scandalous, and rectors themselves are expected to advance science somehow.

In short, it’s demanding work, far more complex than business roles that pay three times more. Add to new political demands that didn’t exist before. Fire someone on orders from above — lose some former friends who’ll consider you a scoundrel. Don’t fire — even worse. And now, ever-growing risks of criminal cases for purely economic offenses. As a result, negative selection occurs: people who could take on this work think it’s better to sleep soundly than eat a bit more heartily.

Well, and given the uncertainty, when no rector knows how long they’ll sit in their chair, the attitude toward all sorts of long-term development programs becomes like toward something completely ephemeral. I think the average rector now finds it hard to imagine having to answer in five years for promises made today. So, university development increasingly follows the principle of ‘the day passed — and good enough,’” says Sokolov.

“The situation has changed. In the past, even in the late Soviet Union, complaints would typically lead to a discussion first. They didn’t punish right away. But in recent years, bitterness has grown — immediately, without meetings or discussions, they launch criminal cases and repressions, dealing with a person right away,” believes Sergei Abramov, corresponding member of the Russian Academy of Sciences, who previously also led the University of Pereslavl-Zalessky.

If we analyze the investigations and verdicts against rectors, we can conclude that in some cases, charges of fraud, bribery, or abuse of office are a pretext, not the cause for a criminal case. Perhaps it’s more about clearing the chair for a new boss, or a signal — and the person leaves on their own.

“The rector position is political, influential. There are always those who want these spots,” says a higher education researcher working at one of Russia’s leading universities, who agreed to speak with T-invariant anonymously. “It’s not always about clearing out, though that happens too. Stakeholders include regional political elites (which in different regions either change or are very stable), and — especially if the university is significant at the federal level — federal political elites and parties. Universities are embedded in the political cycle just like other spheres: theater, hospitals, and so on.”

According to the T-invariant interlocutor, any administrative position in state governance today is non-institutional. “We don’t understand by what parameters leaders are appointed or removed. This is a characteristic feature of authoritarian rule. People are in constant uncertainty, and the ‘rules of the game’ can arbitrarily change depending on very different factors. And it’s unclear what will play the decisive role. Loyalty and readiness to fulfill any demands from above don’t guarantee safety if your position conflicts with the interests of some influence groups. The number of criminal cases against rectors is not only an indicator of the state’s fight against corruption but also evidence of some targeted campaign against these officials. Of course, there are plenty of financial violations in universities. And under existing criminal norms, almost any rector can be prosecuted: too many contradictions in the legislation. However, this doesn’t absolve the rectors and their deputies of responsibility. Alas, there’s too little public oversight and accountability, too many temptations for illegal actions for these people, and not everyone can resist the urge to line their pockets with public money,” believes the T-invariant interlocutor.

“The state interferes too much in university affairs; they’re always ‘under state functionaries,’” says Sergei Abramov. “This is the main reason why it hasn’t worked to transfer science to universities. The Academy of Sciences was dismantled, and there was a lot of talk then, like, no problem, we’ll move science to universities, as in the rest of the world. But neither proper science nor proper education will emerge if universities are managed by bureaucrats. The Academy wasn’t run by officials, especially before 2014, then reforms began, but I don’t see anything like the criminal cases in universities happening in the Russian Academy of Sciences.”

*All subheadings in this material use quotes from songs by Mikhail Krug.