The fifth essay in the “Creators” series is dedicated to Vladimir (Waldemar) Haffkine, the creator of the first effective vaccines against cholera and plague. At the end of the 19th century, Haffkine carried out the first mass vaccination in India. His laboratories have developed and produced tens of millions of doses of cholera and plague vaccines. In the “Creators” project, T-inavariant, together with RASA (Russian-American Science Association), continues to publish a series of biographical essays about people from the Russian Empire who made a significant contribution to world science and technology, about those to whom we owe our new reality.

In the late 1950s, Nobel laureate Selman Waksman, the creator of streptomycin, wrote a book about Vladimir Haffkine(1). He wrote with gratitude and sympathy about the search and discovery, about Haffkine’s hard field work in India, about the mistakes and accusations brought against Haffkine. Waksman understood Haffkine, probably like no one else. This book became the basis of our essay.

Ukraine. Odessa. Early years

Waldemar Mordechai Wolf Haffkin (russian: Владимир Аронович Хавкин, Vladimir Aronovich Khafkin, ukrainian: Володимир Мордехай-Вольф Хавкін) was born on March 3, 1860 (old style) or March 15, new style in Odessa in the Russian Empire in the family of Aaron and Rosalia (née Landsberg) Haffkine. Waldemar Haffkin’s father came from a Jewish merchant family and was raised in the spirit of Western culture. He was not particularly religious, but the boy absorbed the principles and foundations of Judaism from childhood. His mother died when Vladimir (Waldemar) was still just a child. The family moved to Berdiansk on the Azov Sea, where his father worked as a teacher.

At first, Haffkin was educated at home, and in 1870-1872, at a local school. At the age of 12 he entered the Berdiansk gymnasium. Here he excelled in sports and especially in the natural sciences. In 1879, he graduated from high school and entered the natural sciences department of Novorossiysk University in Odessa (also known as ‘Odesa University’ or ‘Odesa National University’). His father was too poor to support a young man in a big city. Waldemar’s older brother came to his aid and gave him 10 rubles a month. The university paid a kind of stipend, that is, it gave out 20 kopecks a day for food. This was enough for Haffkin to somehow make ends meet. He was passionate about science and from his earliest youth was full of sympathy for people. This later determined his life.

At the university, Haffkine studied physics, mathematics and zoology. Very soon, Ilya Metchnikoff, who at that time was a professor of zoology at Odesa University, became his teacher. And Haffkine also decided to become a zoologist. But it wasn’t just science that worried him.

On March 1, 1881, Tsar Alexander II was assassinated by members of the revolutionary organization “Narodnaya Volya” (People’s Will). On March 18, 1882, in Odessa, on Nikolaevsky Boulevard, “Narodnaya Volya” member Nikolai Zhelvakov shot military lawyer Major General Vasily Strelnikov at point-blank range. The preparations for the murder were carried out by the famous revolutionary, member of the “Narodnaya Volya”, Vera Figner.

Students from Odesa University also took part in the activities of “Narodnaya Volya” in Odessa. There is noteworthy information that Haffkine was also associated with Narodnaya Volya, was arrested and spent some time in prison (Haffkine’s biographer Mark Popovski writes about this in the book “The Fate of Doctor Haffkine” (1963) (2).

The conservative regime of the new Tsar, Alexander III, took harsh measures to suppress the terrorist movement in universities and throughout the country. Many students were arrested and exiled, some were executed (Nikolai Zhelvakov was hanged by decision of a military court 4 days after the murder of Strelnikov).

The government and the masses found the main “culprits” for the turmoil quite quickly—they turned out to be Jews. Jewish pogroms began in Odessa. (In 1887, a “percentage norm” was introduced for Jews in gymnasiums and universities: Jews in these educational institutions could not exceed a certain proportion. Haffkine was no longer affected by this restriction, but it greatly influenced the lives of many other Jews, including Selman Waksman).

Officials, the press and student organizations began a systematic attack not only on individual Jews, but also on entire communities, which were called the main cause of all the troubles that befell the Russian Empire. Many Christian students at universities formed paramilitary groups that attacked Jews and incited pogroms.

To protect themselves from pogroms, Jews, not particularly counting on help from the authorities, organized self-defense. On May 3-5, 1881, when the pogrom began in Odessa, self-defense acted quite successfully. But the police not only did not protect the Jews, they arrested about 150 self-defense participants. Among those arrested was Waldemar Haffkine. He was captured with a revolver in his hand. In fact, the self-defense had few weapons—mostly axes, clubs and iron rods. The fact that Haffkine had a revolver can be considered an indirect confirmation of his connection with Narodnaya Volya: professional revolutionaries had weapons. After the arrest, the situation for Haffkine was very difficult. He was threatened with more than just exile. But the teacher saved him.

Professor Metchnikoff learned about the arrest and immediately came to the student’s aid. Metchnikoff acted as a witness for the defense. His authority was so great that he managed to save Haffkine from persecution by the authorities. And Haffkine not only was released, but remained at the university and received a diploma in 1883. He presented a thesis on zoology.

As a result of persecution and imposed restrictions, mass emigration of Jews from the Russian Empire began, especially often they left for the United States. But Haffkine decided to stay in Odessa and prepare for a scientific career.

Odessa at that time was one of the world’s largest microbiology centers. Not only Haffkine’s teacher, Nobel laureate Ilya Metchnikoff, worked there, but also epidemiologist Nikolay Gamaleya, microbiologist Alexandre Besredka (he later worked fruitfully with Metchnikoff at the Pasteur Institute in Paris), and many others. It was in Odessa in 1882 that Metchnikoff discovered the phenomenon of phagocytosis, and at the congress of Russian naturalists and doctors in 1883 he delivered his famous report on the body’s defenses. Thus, one of the most important biological sciences today — immunology — was founded. In 1886, Metchnikoff and Gamaleya organized the first Pasteur Station outside France (Odessa Bacteriological Station) in Odessa.

After receiving his diploma, Haffkine went to work at the Zoological Museum of Odessa, where he spent the next five years (1883-1888). Since he refused to be baptized, he could not count on a professorship, but he was provided with a laboratory equipped specifically for his work. During this period, Haffkine published five important scientific works on the nutrition and hereditary characteristics of single-celled organisms. He participated in the translation from German into Russian of Klaus’s treatise on zoology. He became a real scientist.

But the restrictions imposed on Jews became increasingly strict, and Haffkine’s academic career was closed. In 1888, an event occurred that decided everything for the young scientist: his favorite teacher, Ilya Mettchnikoff, went to work at the Pasteur Institute in Paris.

According to Metchnikoff’s wife Olga, the great scientist explained the reason for his departure: “Thus it was in Paris that I succeeded at last in practising pure Science apart from all politics or any public function. That dream could not have been realised in Russia because of obstacles from above, from below, and from all sides. One might think that the hour of science in Russia has not yet struck. I do not believe that. I think, on the contrary, that scientific work is indispensable to Russia, and I wish from my heart that future conditions may become more favorable in the future.” (3)

Emigration

At first, Haffkine chose Switzerland. Many Jews from the Russian Empire went there to receive university education and work in the field of natural sciences and medicine. In 1888, Haffkine was appointed assistant in physiology to Professor Morris Schiff at the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Geneva.

Selman Waksman recalls visiting the University of Geneva almost 40 years later. He spoke with the university’s professor, Richard Schodat, who told him that before the 1917 revolution, 90% of students in Swiss medical schools were Russian Jews. Of course, it wasn’t because of a good life that this happened. But this was a chance.

Haffkine stayed in Switzerland for a year. Although everything seemed to be going well, there was only one place in the world where he wanted to work — the Pasteur Institute. And in 1889, Haffkine left Geneva for Paris. His teacher, Ilya Metchnikoff, worked there, and Louis Pasteur worked there. The most advanced science was there.

Haffkine was very interested in the work carried out in Paris on the occurrence of diseases in humans and animals under the influence of microbes and the creation of vaccines to protect humans and animals from bacterial infections. And it was in this scientific field that he subsequently achieved outstanding success.

But Haffkine’s first appointment at the Pasteur Institute was as an assistant librarian. Early in the morning before the library opened and late in the evening after it closed, Haffkine could work in the laboratory of Emil Roux. His only hobby at that time, besides work and books, was the violin. His love of music found sympathy among other Odessa emigrants. Metchnikoff himself loved to listen to him.

Haffkin worked at the Pasteur Institute on the protozoa Paramecium (Paramecium Caudatum). He investigated the nature of the infectious disease of these protozoa. In 1890, he published a work devoted to these studies in the journal “Annales de l’Institut Pasteur”. These studies led him to study the nature of adaptation to the environment in ciliates and bacteria, which resulted in another scientific work entitled “Contribution to the Study of Immunity” (1890) (4).

At this time, Haffkine also conducted research into typhoid fever. Metchnikoff noted the work of Haffkine, where he showed that various forms of typhoid bacilli “adapt to life in the watery contents of a rabbit’s eye, but die when suddenly transferred to the broth, which previously was a good medium for their growth. The typhoid bacillus, accustomed to living in broth, quickly dies when transferred to a blood environment, but, gradually adapting to such an environment, grows in it even better than in broth.” Then Haffkine will find his knowledge of growing crops in various environments very useful. His fate was such that everything he did was preparation for the main task of his life — the creation of vaccines.

Cholera research begins

Both his own research and the entire scientific situation at the Pasteur Institute led to Haffkine becoming interested in cholera.

Robert Koch, the famous German bacteriologist, went to Egypt and India in 1883, where he managed to isolate a pure culture of Vibrio cholerae, which, as Koch himself was sure, was the cause of the disease. Not all scientists accepted Koch’s theory, but not at the Pasteur Institute: here Koch was supported and Vibrio cholerae was studied seriously. Waldemar Haffkine also joined these studies.

He first demonstrated that when passing through guinea pigs, Vibrio cholerae increased its virulence, which was an important argument in favor of the infectious nature of the disease. Haffkine then managed to obtain a weakened drug by growing vibrio in a stream of air.

In 1892, Haffkin published a short paper on cholera in the guinea pig, where he described his new method; in the same year another note was published about cholera in a rabbit and a pigeon. As a result of inoculating animals first with a weakened drug, and then introducing them with a more virulent culture, a high degree of immunity was obtained.

In fact, Haffkine has already done everything. The theory of the cholera vaccine was created. He learned to strengthen vibrio, that is, increase its concentration by passage, and weaken the culture by growing it in the open air (later Haffkine used heating to weaken the culture).

Vaccination with a weakened vaccine “triggered” the immune system, and the second vaccination strengthened it (this is a kind of “booster” vaccination). Everything worked in animals. But how far it was from actually using the vaccine on humans!

The successes achieved by Haffkine impressed Pasteur so much that when Prince Damrui, brother of the King of Siam, called the Institute and asked Pasteur to give him a cure for cholera, the famous scientist turned directly to Haffkine.

In 1892, Pasteur asked the Russian government for permission to test the method in the Russian Empire, where cholera was rampant at the time, but the request was rejected. The epidemic grew and in 1893 came to St. Petersburg. On November 1, 1893, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky died of cholera. Perhaps if the Russian authorities had listened to Pasteur and Haffkine and started vaccination on time, many, many people could have been saved. And Tchaikovsky would have lived for many more years.

In 1892, Haffkine was appointed to a research position at the Pasteur Institute and continued to work on cholera.

At this time, a cholera epidemic began in India and Indochina (the fifth in the 19th century). From there, the disease spread throughout Asia and already threatened European countries.

In 1890, the Spanish bacteriologist Jaime Ferran y Clua, building on Pasteur’s ideas about immunizing the body by introducing weakened or dead microbes that cause infection, attempted to create a cholera vaccine using a live culture. But Ferran’s report of the creation of a cholera vaccine has been disputed. He failed to develop the correct dosages and, as a result, caused cholera infection with his vaccination more often than he protected against the disease. What Ferran couldn’t do and what Haffkine could do: control the strength of the vaccine.

In addition, Ferran encountered serious resistance from church authorities, who were against vaccination in principle. We all know the arguments of anti-vaxxers well from the recent COVID-19 pandemic. For more than a hundred years they have changed little. Pasteur wrote that there was no evidence of the practical benefits of the Ferran vaccine.

Unlike Ferran, Haffkine has moved far ahead. He obtained a highly active culture by successively passing the cholera pathogen through animals. And then he weakened it by growing it at a high temperature (39°C) and injected it subcutaneously into guinea pigs. The result was absolute immunity.

On July 9, 1892, Haffkin presented the results of his first experiments at the Paris Biological Society in a work entitled “Asian cholera in guinea pigs.” He soon began experimenting with rabbits and pigeons. Treatment of these immunized animals with active cultures obtained from Assam (Indochina) and Ceylon did not cause any pathogenic effect: the Russians were protected from cholera, which was killing tens of thousands of people.

Thus, Haffkine proposed using a weakened culture rather than an active one for vaccination purposes. Haffkine believed that this method would protect the human and animal body from cholera infection. Having convinced himself of the harmlessness of the new vaccine by vaccinating animals, Haffkine began vaccinating people.

On July 18, 1892, he injected himself subcutaneously with a large dose of a weakened cholera vaccine. He developed a fever, a headache, and felt weak. Six days later, one of his emigrant friends from the Russian Empire gave Haffkine a second dose of the vaccine. The temperature rose again, but the general weakness was more short-lived.

Science historian Marina Sorokina writes about Haffkine’s first experiments on humans: “After that, he carried out a similar experiment on three volunteers from Russia (Georgiy Yavein, Mikhail Tomamshev and Ivan Vilbushevich) and came to the conclusion that a person acquires immunity to cholera infection in six days after the second vaccination. He later vaccinated other volunteers, one of whom was Ernest Hanbury Hankin (1865–1939), a fellow at St John’s College, Cambridge. A chemist and bacteriologist who studied malaria, cholera and other diseases, working in the northwestern provinces of India, Hunkin became an active and effective assistant and supporter of Haffkine. It was he who published information about Haffkine’s method in the British Medical Journal, talking in detail about the new drug and his personal experience of vaccination.”

Bacteriologist E. Podolsky in his work “The first problem that Haffkine had to solve in his search for a remedy for cholera was the fixing of a cholera virus to a well-defined strength. He solved this problem in the following manner: by attenuation of the virus – that is, the cholera germ – and by exaltation of the virus. The virulence of the germ is diminished by passing a current of sterile air over the surface of the cultures, or by various other methods. The virulence is exalted or increased by the method of passage; that is, by growing the germ in the abdo- men in a series of guinea pigs. By the latter method, the virulence after a time is increased twentyfold, i.e., the fatal dose has been reduced to a twentieth of the original. Cultures treated in this way constitute the virus exalté. Injection of the virus exalté under the skin of an animal produces a local destruction of tissue followed by the death of the animal. But if the animal be treated first with the attenuated virus, the subsequent injection of the virus exalté produces only a swelling of the tissue at the site of the injection. After inoculation first of the attenuated and after- wards of the exalted virus, the guinea pig acquires a high degree of immunity. Dr. Haffkine also proved the harmlessness of the vaccine by inoculating himself with it and by careful and patient observation on other scientists who allowed themselves to be inoculated. This was the first stage of Haffkine’s researches.”(5)

But not all scientists believed not only in the possibility of vaccination, but even in the bacteriological causes of the disease itself. And among the opponents there were serious specialists.

In a letter written on November 20, 1892, Louis Pasteur wrote: “Do you know that a new great discovery may be in preparation regarding cholera? Pettenkoffer reports in his publication from Munich that he swallowed a cubic centimeter of pure culture of the virulent bacillus without experiencing any discomfort except a slight diarrhea; that he noted a very abundant culture of this bacillus in his intestines; that another researcher had done the same thing with the same results; that the river in Munich, into which their excrement fell (which scientists are cautiously keeping silent about), gave a culture of the bacillus in large quantities, and that cholera did not manifest itself in any of the residents… Haffkine learns about all this with some consternation. For eight days now he has been in London to ask the English authorities for permission to travel to Calcutta to conduct an experiment that he intended to carry out in the kingdom of Siam.”(6)

The experiment of Max Pettenkofer — an outstanding hygienist and, of course, a brave man — has gone down in history as clear evidence of the readiness of doctors and scientists to sacrifice themselves. But he did not believe that Vibrio cholerae was the cause of the disease. This is a case where senseless courage could lead not only to the death of the scientist himself, but also to a real epidemic. Why did neither one nor the other happen? It was just luck.

Haffkine was ready to test the effectiveness of his vaccine against human infection in those areas where cholera caused epidemics and spread rapidly. To this end, he first planned the trip to Siam mentioned by Pasteur.

By coincidence, the British ambassador in Paris, Lord Dufferin, the former Viceroy of India, learned of Haffkine’s research on cholera. He sent a letter to the British Secretary of State for India and Lord Lansdowne, then Viceroy of India, offering to give Haffkine the opportunity to continue his research on cholera in India.

Path to India

Having received an invitation from the British authorities, Haffkine arrived in London and gave a series of lectures at research laboratories and King’s College. These lectures, devoted mainly to his ideas about preventive vaccination against cholera, were well received. He was given the opportunity to go to India and arrived in Calcutta in March 1893. There he immediately began his work. Calcutta was chosen because it was considered the most cholera-affected part of the country.

His closest friend and comrade-in-arms, W. J. Simpson, later described Haffkine’s work in India. He stated that Haffkine had been able to prove that he had had a vaccine that had protected animals from the fatal disease caused by cholera bacillus. The harmlessness of the vaccine had been established through very careful and patient observations of the doctors and scientists who had been vaccinated after the discovery… After training Simpson’s laboratory assistants in the method of preparing vaccines, he had accepted an invitation to Agra, where 900 people had been vaccinated. According to Simpson’s account, after the start of vaccinations, requests to send the vaccine from different places in Northern India came so often that Haffkine could not fulfill them all. However, within a year he had vaccinated around 25,000 people.(7)

The result of two years of vaccinations and studies showed that, despite the incomplete protective effect of the first four days and the gradual disappearance of resistance in those vaccinated with a weak dose of the vaccine, which a significant part of the vaccinated received during the first six months, the mortality rate among vaccinated compared to unvaccinated people decreased by more than 72 %. Subsequently, this ratio improved and amounted to 80%. In addition to the evidence of the effectiveness of vaccinations obtained from direct observation of humans during cholera epidemics, an interesting set of experiments carried out by Professor Koch, Professor Pfeiffer and Dr. Kolle in 1896 allowed them to prove the protective properties of vaccinations in another way. They vaccinated a large number of students and doctors with the Haffkine vaccine and discovered that the serum of the vaccinated had a rapid and absolutely destructive effect on Vibrio cholerae.”

The support of his colleagues and, first of all, Koch helped Haffkine a lot and convinced many doubters. Koch was convinced that Haffkine was on the right track.

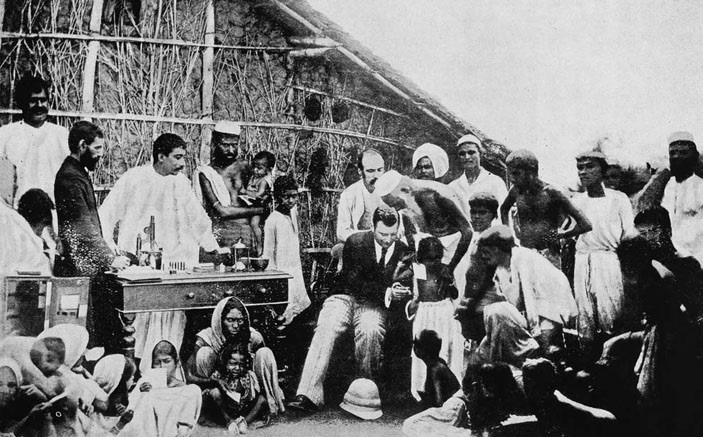

Haffkine inoculates the local population against cholera. Calcutta, 1894, photo from the archives of the Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine in London.

Haffkine was not a doctor, he was first and foremost a zoologist and then became a bacteriologist. When he arrived in Calcutta, he initially met with fierce resistance from both the local population and British officials. It was only when he had himself and four Indian doctors who accompanied him to the first village in Upper Bengal, where cholera was rampant, vaccinated that he was able to convince the inhabitants that the vaccinations were safe.

Volunteers came forward and in one day 116 of the 200 inhabitants were vaccinated. Encouraged by the initial results, Khavkin embarked on an expedition lasting almost two and a half years, which led from Agra through Bengal, Assam, the north-western provinces, Punjab and Kashmir.

At the same time, many newspapers ran active propaganda against him and even claimed that he was a Russian spy. Opponents of smallpox vaccination also directed their attacks against Haffkine, especially after he had successfully vaccinated two regiments of soldiers stationed in Lucknow. Many British officials wrote that the vaccine was at best too weak to have any significant impact on the course of the epidemic. The religious beliefs of some tribes were against vaccination. There were even rumors that some Muslims in East Bengal tried to poison the “white doctor” with snake venom.

The problems that Haffkine faced were described by bacteriologist R. Pollitzer, the author of a fundamental work on cholera, as follows: “The difficulties of applying Haffkine’s method of vaccination against cholera on a wide scale were enormous. As he himself admitted, a particularly difficult task was maintaining a sufficient quantity of vibrio of a fixed strength through the continuous passage of animals. In large-scale practice it was often impossible to administer second doses, so that of the 40 thousand people vaccinated before 1895 in India using the Haffkine method, only a third received them.”

In the summer of 1895, a report was published in Calcutta on the report of the government bacteriologist Haffkine on two and a half years of work in India. It presented the results of a survey of 42 thousand people. The report emphasized that cholera vaccination had fully met all expectations. Mortality from cholera fell by 72%.

Haffkine wrote in an 1895 article: “The evidence so far accumulated speaks strongly in favor of cholera vaccination, and my own conviction in this matter is becoming more and more strengthened. However, the special responsibility that lies with me in this matter forces me to note that the number of observations is not yet very large; it is desirable that the results obtained be confirmed by new and more extensive statistics.

When, in relating to Professor Koch the data of my report to the Government of India, I said that, in my opinion, the results obtained proved the effectiveness of the method, but that I considered it necessary to do everything possible to confirm them with new observations, I was very glad to learn that for Professor Koch the demonstration has already been completed; that he considers the protective power of the method to be conclusively established by the observations so far collected in India; that further improvements and simplifications are possible, but that the main question, the main part of the problem, is solved by the facts recorded in the above report.”

As we noted above, Koch already had his own arguments in favor of the Haffkine cholera vaccine.

Return to Europe

For continuous hard work for two and a half years, Haffkine had to pay a heavy price. In August 1895, he was lying in a Calcutta hotel room suffering from malaria. He was asked to leave India, but feeling that his task was not yet completed, he asked the Indian authorities for permission to return.

In Europe, Haffkine first went to Germany and France. He presented Koch with the data contained in his report to the Government of India, and emphasized that he considered it necessary to do everything possible to confirm his results with new observations. Koch was very pleased with these results and told Haffkine that he considered the demonstration to be complete, that the protective power of vaccination had been fully proven.

Haffkine then went to London, where in December 1895 he presented a report to the joint council of the Royal Colleges of Physicians and Surgeons on the results of the use of anti cholera drugs.

At the conclusion of his lecture, he said: “Mr. Chairman and gentlemen, on the day when I came back from my expedition to India, I found my former chief, M. Pasteur, lying on his bed of death. Whatever might have been his appreciation of the work done in India, there can be only one desire on my part, that all the honour for the results which may possibly come out of my efforts, should be referred to him, to his sacred memory.”(8)

Discussing Haffkine’s speech on December 21, 1895, the British Medical Journal described his work in India to prevent cholera: “Dr. Haffkine’s work is of the highest scientific value and promises to confer a great boon on our Indian Empire. It has been carried out under circum- stances of the most remarkable self-sacrifice and devotion to the interests of humanity and of science. He has given many of the best years of his life to this research, and has with unwearying industry and transparent sincerity worked out in India all the details which can test the value of this new gift of science to life-saving purposes without fee or reward other than his own conscience, his love of humanity, and his scientific devotion. Dr. Haffkine has with steady diligence and unquestionable enthusiasm braved every danger, and endured the extremes of climate and of unhealthy seasons. He has listened to the appeals from every direction regardless of personal risk and unmindful of his own health, which has suffered greatly. He returned to Europe greatly debilitated by the continuous trials of his arduous labours.” (9) This was great recognition.

Cholera vaccinations have been so successful that a large number of reports have been published on the effectiveness of vaccination in reducing morbidity and mortality. The high demand has led to numerous laboratories being set up in India to produce the vaccine. The Indian government was asked to provide financial assistance to Haffkine. In March 1896 he returned to India (Calcutta). In the course of further work, he managed to vaccinate another 30 thousand people against cholera.

Plague pandemic

Soon after Haffkine returned to India, the government of the country asked him to go to Bombay to find out the cause of the bubonic plague epidemic that had begun there. The government hoped that Haffkine would be able to develop a vaccine against this disease.

Haffkine arrived in Bombay on 7 October 1896 and immediately began setting up a laboratory at Grant Medical College. The laboratory consisted of one room and a corridor. The entire staff consisted of one clerk and three assistants. Haffkine lived in the same college.

The plague epidemic that swept through India at that time was described by Colonel S.S. Sokhei, long-time director of the Haffkine Institute: “The present pandemic plague which spread from Yunnan to Canton and to Hong Kong in 1894 reached Bombay in 1896, and in a few years invaded the whole of India. It also spread to many other parts of the world like Australia, South Africa, North and South America, Egypt, several Mediterranean Ports, England and France. This pandemic is now in a quiescent state and is obviously on the way out. . . . The historical records indicate that plague pandemics have a characteristic cyclical course. Starting from one or other of the endemic centres pandemics have spread over the world, raged with varying intensity for a century or more, caused great loss of life and came to an end of their own accord only to begin again after a lapse of relatively long periods of time.”(10)

A more detailed description of the plague epidemic and Haffkine’s contribution to the development of a suitable vaccine is given by Podolsky: “It was in Hong Kong that the cause of the plague was discovered. It was during an epidemic in 1894 that the Japanese Government sent Drs. Kitasato and Aoyama to investigate the disease. They arrived in Hong Kong on June 12th, and two days later Dr. Aoyama made an autopsy on one of the victims and Dr. Kitasato found numerous bacilli in the heart, blood, liver and spleen. Similar bacilli were found also in a living victim of plague on the same day. On June 15th cultures were developed, and with the exception of pigeons, all the animals inoculated by Kitasato died with the identical signs of plague in human beings.”(11)

Dr. Alexandre Yersin, sent by the French government, arrived in Hong Kong on June 18 and independently discovered the same bacillus, which was named Bacillus Pestis (the plague bacillus was later named Yersinia pestis in honor of Dr. Yersin).

Podolsky writes: “Some two years later, in 1896, Bombay, which had an active trade with Hong Kong, was visited by the plague. Bombay had been free from this disease for nearly two hundred years. . . . It was then quite apparent that the rats, transported in the ships, were the carriers of the disease. Stationed at Bombay was Waldemar Haffkine who had attained a reputation as a very competent bacteriologist. It was up to Haffkine to attempt to find a method of controlling the plague. . . . After the discovery of the plague germ by Kitasato and Yersin in 1894, many bacteriologists undertook numerous investigations in this field. One of the most noted of these was Haffkine, who was interested mainly in developing a vaccine. He succeeded in protecting human beings against plague by the inoculation of killed cultures.” (12)

Three days after arriving in Bombay, Haffkine began experimental work. If Yersin tried to cure the plague with an anti-plague serum, then Haffkine tried to develop a method of preventing infection, leading to the development of immunity against the disease. The question was how to weaken the plague microbe. Various methods were tested: treatment with chloroform and phenol, heating, drying. Dried organs from animals that died from plague have also been used as potential vaccines. Since not all bacterial cells died, the drying method had to be abandoned. Heating cultures to 65°C did not provide immunity in rats, although it was later found to induce immunity in humans. Haffkine worked 12-14 hours a day, while still managing to give numerous lectures to doctors on the problems of plague. One of his assistants became depressed, and the other two, exhausted by their hard work, left him. But he stayed.

In December 1896, the vaccine was ready. Haffkine developed a method for growing microorganisms in the form of stalactites by applying a layer of coconut or animal fat to the surface of the broth in a flask. To enhance growth, the flask was shaken periodically. After six weeks of incubation, the culture was heated. The microbe died and turned into a full-fledged vaccine. The first experiment was carried out on twenty freshly captured rats. Half of them were vaccinated, then an infected rat was placed in a cage. Within 24 hours, nine unvaccinated rats fell ill, while all vaccinated rats remained healthy. The vaccine also proved successful in protecting rabbits: after subcutaneous injection of a heat-sterilized broth culture, rabbits acquired immunity to the plague. In January 1897, Haffkine published his method of preventive vaccination against plague.

Let’s remember: Haffkine arrived in Bombay on October 7, 1896, and in January the vaccine was ready—3 months. Even COVID-19 vaccines were not created at such a speed. Considering the conditions under which Haffkine worked and the level of science at the end of the 19th century, this is a bit like a miracle.

On January 10, 1897, Haffkine inoculated himself with 10 milliliters of the most powerful vaccine preparation. This was done secretly, in the presence of only two people: the doctor who administered the vaccine and the director of the college. The vaccination caused a severe reaction, but this did not prevent Haffkine from continuing his work and taking part in an important conference.

The call for volunteers was successful, especially among college students, both European and Indian, and among the Bombay intelligentsia. Following Haffkin’s example, physicians and prominent citizens of Bombay publicly inoculated themselves to encourage others to undergo similar treatment.

Vaccinations were given to half the prisoners at the House of Correction where the plague broke out. This was an important experience: the prisoners were in the same controlled conditions and the result of the vaccination was clear. The vaccinations worked. Almost none of the vaccinated prisoners contracted the plague, while those who were not vaccinated got sick and died. After this, Haffkine’s method became popular. This required bulk production of the vaccine.

The laboratory required more spacious premises. Then a very influential patron came to Haffkine’s aid—Sir Sultan Muhomed Shah Aga Khan III (1877–1957), the 48th Imam of the Shia Ismaili Muslims. Marina Sorokina writes: “Educated in Great Britain, the young Aga Khan supported scientific innovation, especially in the field of medicine. He suggested that Haffkine give preventive vaccinations to the Muslim community of Bombay, and about half of the community (10–12 thousand people) received “Haffkine’s lymph.” The results were again impressive, and in October 1897, the Aga Khan provided the scientist with a building next to his own residence to house the anti-plague laboratory.”

The laboratory was transferred there. The staff has been significantly expanded.

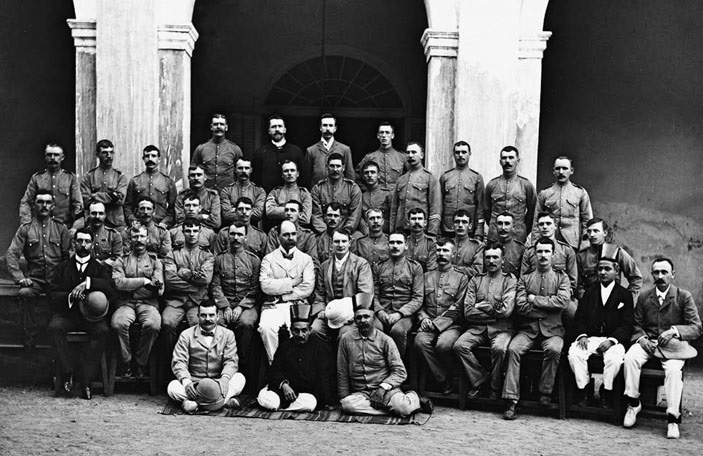

Haffkine (in the second row in the center, with a light pith helmet) with employees of the Anti-Plague Laboratory in Bombay. India, 1902–1903

In March 1899, the demand for the vaccine from all over the world became so urgent that even more comfortable and spacious premises were required. On 10 August 1899, Lord Sandhurst, Governor of Bombay, officially opened a plague research laboratory at the Old Government House in Parel, of which Haffkine became the director.

Meanwhile, the plague had reached epidemic proportions. Ruling circles reacted to Haffkine’s vaccine without much sympathy. They relied more on quarantines and movement restrictions.

An anti-plague mission was organized, headed by a British general. Military measures were introduced, detachments visited every home of local residents. The sick were sent to hospitals, and their loved ones to concentration camps or quarantine points. The homes themselves were thoroughly disinfected.

Unfortunately, these sanitary measures achieved little except human suffering. A microbe capable of surviving and reproducing in many living systems, even soil, could hardly be destroyed by isolation.

When the small Portuguese colony of Daman (10 thousand inhabitants) was hit by a plague epidemic, many residents fled. The villages were surrounded by the army, which prevented any movement within or outside the colony. Haffkine sent two of his most reliable assistants there, who within two months vaccinated 2,200 people (6,000 refused vaccinations). The results reported in the Bombay newspapers strongly indicated the effectiveness of the vaccine. 36 people from the vaccinated group died, and 1482 from the unvaccinated group, i.e. almost 15 times more. Even considering that the unvaccinated group was two and a half times larger, this is a strong result.

This and other results showed that even if vaccination with the anti-plague Haffkine’s drug does not prevent infection, the mortality rate is reduced by 85-90%. All other anti-plague drugs were ineffective. As a result, a movement arose in India in 1898 to replace “hygienic” military measures with bacteriological, prophylactic or preventive methods. It bore fruit.

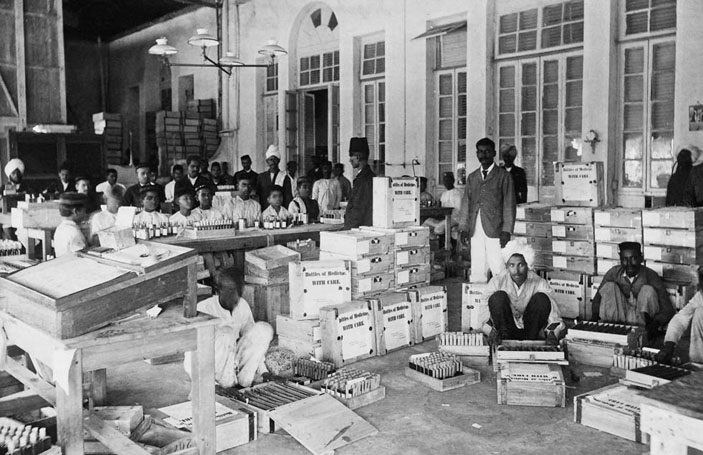

In the vaccine distribution department of the Haffkine Anti-Plague Laboratory in Bombay. India, 1902–1903.

The Indian Anti-Plague Commission conducted a thorough study of the anti-plague Haffkine’s drug and found it safe, since it was already widely used in various parts of India without causing concern or causing any harmful effects. The belief in the benefits of preventive vaccinations against plague became more and more widespread.

Each subsequent year there were new outbreaks of plague. In 1901, the disease assumed even greater proportions. It was decided to carry out intensive anti-plague vaccination throughout Punjab. There is an urgent need for large supplies of vaccine.

Numerous vaccination centers have been opened in Bombay. Haffkine’s drug was sent in thousands of doses to England, France and other countries. A new term even appeared in English magazines: “to haffkinize,” that is, to do a Haffkine vaccination.

Haffkine, in his report on the work of the Bombay Research Laboratory for the years 1896-1902, reports that in the first four and a half years after the creation of the plague vaccine, i.e. up to May 31, 1901, 2,380,288 prophylactic doses were manufactured and distributed in India and abroad. Over the next year, another 486,753 doses were distributed.

The plague has receded.

And Queen Victoria awarded Haffkine the Order of the Indian Empire.

Haffkine’s vaccinations seriously influenced the development of science. The eminent British bacteriologist Professor Almroth Wright acknowledges this in his report on the first anti-typhoid vaccinations, published in the Lancet on September 19, 1896. He writes: “I need hardly point out that these anti-cholera inoculations have served as a pattern for the typhoid vaccinations detailed above.” (13).

Haffkine’s laboratory was engaged not only in vaccine production and vaccinations. Together with colleagues and co-authors E. H. Hankin and N. F. Surveyor, Haffkine searched for the plague bacillus in nature and explored the ways of its spread. “Circumstantial evidence” led him to conjecture that “the plague in Bombay had remained for a considerable time restricted to certain houses in Mandvi whose inhabitants were workers in other parts of the town, viz., in the docks and elsewhere, ” and that “of the various races and castes, the Jains, at that time were mostly affected.” (14).

Haffkine wrote: “The circumstances referred to seemed to show that the people were not favourable carriers and disseminators of infection; that the plague was not carried by water – as cholera is for the affected houses had the same supply as many others; that plague was not carried by atmospheric air, which would have rapidly scattered it over large areas; that it was not spread by winged or other insects migrating readily from house to house; but that, of parasitic vermin, it might be carried by bugs, which stick not only to houses, but even to the same pieces of furniture, or by fleas which remain in the earth, sweepings and floors of houses, and which had been suspected to be carriers of famine fever. The consideration shown by Jains to bugs and other in- sects, which they do not destroy, but are said to go so far as to feed artificially, seemed to me to conform with the hypothesis.” (15)

However, the results obtained were generally negative. Eventually, Haffkine turned to the work of the French doctor Simond, who suggested that fleas were the carrier of the plague. Haffkine writes: “The idea seemed to him extremely plausible, and he endeavored to prove that plague rats were infective only as long as they were covered with fleas; that plague bacilli were discoverable on such fleas; that by means of the latter a plague rat might trans- mit plague to another rat kept at a little distance from it; and that rat fleas might attack men. . . . Unfortunately, Dr. Simond’s experiments, in a large proportion of instances, gave negative results; while the cases in which the experimental animal did get the disease were so few that they might be attributed to some adventitious circumstances.” (16)

But in this case, Haffkine was wrong, and Simon was right — fleas, not bedbugs, are carriers of the plague.

In June 1899, Haffkine traveled to England to report to the Royal Society and various medical organizations on the success of vaccination against cholera and plague. His performance received universal acclaim. Lord Joseph Lister, President of the Royal Society, Almroth Wright and many other prominent British scientists and clinicians warmly welcomed Haffkine. His return to India in the fall of 1899 was greeted with great enthusiasm by the local population, who were already tired of the sanitary measures implemented by government officials to contain the plague. These officials began to consider Haffkine an enemy of the colonial regime. This was also facilitated by the fact that Indian nationalist newspapers advocated the Haffkine vaccine.

On the other hand, British newspapers accused Haffkine of collaborating with the Russians and almost of espionage. There were even accusations that vaccines made people more susceptible to other diseases.

The Malkowal Disaster

In November 1902, a tragedy occurred in the village of Malkowal in the Indian state of Punjab. Of the 107 people who received the vaccine, 19 developed tetanus and died within a few days. The Government of India appointed a commission of inquiry which reported that tetanus was introduced into the vaccine before the vaccine vial was opened at Malkowal. The panel speculated that this was either due to insufficient sterilization or the vial being filled from a large flask without proper precautions. The results obtained by the commission were transferred to the Lister Institute in Britain.

The commission did not listen to Haffkine, who became the main accused. In vain he submitted reports asking to study in detail the method of preparing the vaccine. Fortunately, the leaders of the Lister Institute did not agree with the accusations against Haffkine.

Haffkin himself described (report for 1902-1904) the conditions under which the tragic error occurred as follows: “It was when using the material prepared in September-October 1902 that 19 cases of tetanus occurred in the village of Malkowal, in the Punjab. Some 120,000 other people had by that time been in- oculated with the same material, and the reports sub- mitted from the Punjab and the rest of the country testified to the harmlessness, as well as the effective immunising properties of that material. The mortality from plague amongst those inoculated was reduced to a fraction of what it was in the non-inoculated.”(17)

He further writes: “It is known that a very minute quantity of contaminated matter is required to cause tetanus. A surgical instrument, scrupulously clean, i.e., containing no visible trace of impurity of any kind, may cause the disease, if not preliminarily sterilized. The experiments of Vaillard and Rouget showed that to cause a guinea-pig death from tetanus, it is sufficient to inoculate it with a particle of earth in which cultivation reveals the presence of 2 or 3 tetanus germs only; ani- mals injected with such a contaminated particle may exhibit a disease of equal severity, and all die in 3 to 5 days. The material used at Malkowal might have got contaminated either at the Laboratory or elsewhere… The following facts were against the admission that the tetanus germs had got into the prophylactic in Bombay. The cases of tetanus occurred in persons inoculated from a bottle belonging to brew 53 N of 19th September 1902. This bottle formed one of five filled from the same brew-flask, No. 53 N. That the brew was not contaminated was proved by the persons who were inoculated, at other places, with the remaining four bottles having had no tetanus. A fluid in which tetanus germs had gained entrance and lived for some time gives out a foul odour which is smelt at a distance by by-standers when the vessel is unstoppered… The inoculators had no instruction to test bottles by smelling, but many of them did so. On this occasion, at Malkowal, the bottle, when opened for inoculation, six weeks after it had been prepared in the Laboratory, was smelt, and no odour was found in it. A fortnight after the bottle was used it was again examined, and by that time a smell had developed in the remnants of the fluid. The microbe of tetanus was then also found in it, in symbiose with a micrococcus.” (18)

Throughout the investigation, Haffkine rightly continued to assert that the vaccine sent from the laboratory was not contaminated with tetanus and that the contamination must have occurred outside the laboratory.

Haffkine remained cheerful throughout the investigation, which lasted more than a year, but it was a difficult ordeal for him. On April 30, 1904, he left Bombay for a year’s leave pending the final decision of the government. He was relieved of his position as director of the Plague Research Laboratory. He spent most of his time in Europe, visiting various laboratories, where he had the opportunity to present his version of the tragedy to several outstanding scientists, who unanimously absolved him of all blame.

Later (in 1930), the British journal Lancet spoke about this case as follows: “In 1896 the disastrous epidemic of plague in India led the Government to entrust Haffkine with the preparation of a vaccine against that disease, in view of his discoveries with vaccine as a preventive of cholera. The work was immediately commenced, and its results and extension were regularly reviewed in the medical and scientific press. In 1900 the Indian Plague Commission reported thoroughly on the whole matter, found that the use of the vaccine was attended with a diminution of the attack and death rates, and the establishment of a temporary protection, while the final recommendation of the Commissioners was that, under safeguards and in conditions of accurate standardisation and absolute care, the procedure should be encouraged wherever possible, and in particular among disinfecting staffs and the attendants of plague hospitals. A series of fatalities occurred in 1902 which for the time cast a suspicion upon the methods of manufacture of the prophylactic, but inquiry into the actual incidents made it clear that the tragedies were due, not to carelessness in the laboratory, but to a gross neglect of ordinary precautions in administration. That the activity of the Indian authorities in proceeding without break in inoculation against plague on a large scale was in no way unabated can be seen by the results of 30,000 cases of inoculation… But although inoculation proceeded, Haffkine’s control of the work had been suspended by the India Office, and he remained unemployed. The sufferer in a prolonged dispute who obtains a verdict in the end is never repaid for his anxiety, but throughout his period of trial Haffkine bore himself with the greatest dignity; he received many congratulations upon the recognition which he finally received from the India Office and upon his resolution to return to India. Today the verdict on Haffkine’s labours which is generally accepted is that the vaccine, when used in epidemic, tends to reduce mortality by 85 per cent. What this means when we consider the millions of doses that were issued in India can hardly be conceived.”(19)

A similar opinion was shared by those who knew the details of the tragedy in Malkowal. General S. S. Sokhey, the former director of the Haffkine Institute, wrote about this in a personal letter to Selman Waksman (It should be noted that there is a slight confusion: in 1902, of course, there was no Haffkine Institute, but there was a Plague Research Laboratory. S. S. Sokhey became director of the Haffkine Institute already in the late 1920s, but in his letter he calls the Laboratory an Institute).

Sokhey writes to Waksman: “In the Malkowal affair people injected with plague vaccine from one vial sent out from the Haffkine Institute died of tetanus and that was attributed to the fault of the Haffkine Institute. But it was shown later that something like 20 days had elapsed between the vial leaving the Haffkine Institute and its being used in the field. If tetanus had got into the vial at the Haffkine Institute it would have fully devel- oped into a toxic tetanus culture by the time it was used and people injected with it would have died im- mediately from this toxin. But they died 7 to 10 days after the injection had been given. That was considered to be a proof positive of the fact that the vial was contaminated on the spot where it was used. This is how it happened. In those days plague vaccine used to be sent out in vials closed with rubber stoppers, and the assistant to the doctor when he removed the rub- ber stopper slipped the rubber stopper through his fingers and it fell on the ground. He lifted it up and put it back on the vial to shake the contents. And that is how the vaccine got contaminated.”(20)

Haffkine Institute

Only in 1907—three years after Haffkine’s removal from work—the Indian government, having found no evidence to support its accusations, invited the scientist to return to India.

Letters of gratitude poured in from all over the world in Haffkine’s defense. Eventually he decided to return. Since the post of Director of the Bombay Laboratory was filled, he agreed to work in Calcutta. He continued to work, but his strength was undermined, not so much by intense work as by unfair accusations. On reaching retirement age in 1914, he left India.

Despite the fact that many attempts were made to improve the original method of obtaining a plague vaccine developed by Haffkine (in three months!), they were generally unsuccessful. The superiority of the Haffkine vaccine over other types of plague vaccines has been widely demonstrated. And it became the quality standard for decades. Although the incidence of plague in India has decreased, the demand for the vaccine continued to increase. By 1930, more than 33 million doses had been distributed within 34 years of the vaccine’s development.

In 1925, the Bombay government renamed the Plague Research Laboratory the Haffkine Institute to honor the memory of a man who brought great benefit to India and its people.

About Haffkine, Podolsky wrote: “Haffkine was always immersed in research. No sooner had he disposed of one problem than he started on another. In World War I, the British forces in France had prophylactic inoculations against typhoid, but not against paratyphoid A and B. In view of the arrival of troops from India and the Mediterranean region, it was urged that the complete inoculation should be performed. But Sir William Leishman, Director of pathology of the expeditionary forces, opposed immediate action because he feared severe reactions, which might impede military reinforcements. A committee of noted pathologists was appointed to consider the question, of which Haffkine was a member. His arguments went a long way to convince Leishman. After a trial on 300 men, the vaccine was generally used in all armies… Haffkine was a tireless worker, who neglected his own welfare for the welfare of others. He was well liked by those with whom he came in contact.” (21)

Last years

After retiring, Haffkine settled in France. He lived mainly in Paris and Boulogne-sur-Seine. He increasingly sought solitude. He completely abandoned his scientific career, although he remained a member of various English, French, American and Indian scientific societies and wrote in Russian, French and Dutch scientific journals. His works were mainly devoted to topics that he studied throughout his life.

His retirement coincided with the beginning of the First World War and the eve of the revolution in the Russian Empire. This did not allow him to travel freely to his homeland, although in 1927 he paid an extended visit there. He visited Odessa and traveled around the country.

He remained a bachelor all his life. Apparently, he believed that he would not be able to impose on a woman the lifestyle that he led in India — entirely devoted to scientific work and saving people. To those who saw him in London in 1899, Haffkine seemed a lonely, serious, self-absorbed, but at the same time handsome man.

At a reception given to Haffkine in London in 1899 by the Jewish organization “The Maccabees”, Lord Lister emphasized the enormous benefit that Haffkine’s work brought to the people of India and the entire British Empire. At this reception, Haffkine stated that throughout his time working in India, he had never forgotten the suffering of his fellow Jews under the Tsarist regime.

Podolsky wrote about the last years of Haffkine’s life: “He sought scientific backing for many of the hygienic laws laid down by Moses and others in ancient times. The microscope he stated justified a great many of these regulations. As an example he cited the law of the thorough removal of animal blood which could easily be invaded by germs and cause serious diseases. He regarded his religion as a form of discipline. It was like science. In order to accomplish anything in science we must know what has been accomplished before. In a similar way we must learn from the wisdom of the past.”(22)

After retirement, Haffkine devoted much time to studying Judaism. He was convinced that it was Judaism that served the Jews well and that their future greatly depended on the preservation of religious traditions. He believed it was of utmost importance to promote the study of the Bible and outlined his views in an essay published in 1916: “a brotherhood built up of racial ties, long tradition, common suffering, faith and hope, is a union ready-made, differing from artificial unions in that the bonds existing between the members contain an added promise of duration and utility. Such a union takes many centuries to form and is a power for good, the neglect or disuse of which is as much an injury to humanity as the removal of an important limb is to the individual.”(23)

Although Haffkine did not receive a religious upbringing in childhood and adolescence, towards the end of his life he became a deeply religious believer. He converted to Orthodox Judaism. In April 1929, Haffkine bequeathed securities placed in a Swiss bank to Jewish religious schools in Eastern Europe. After his death, a corresponding fund was created.

On April 17, 1928, Haffkine finally settled in Lausanne. He died in this city on October 26, 1930. He died, as he lived, alone.

Grave of V. A. Haffkine. Lausanne, Switzerland. Photo Alexander Duel

When news of his death reached the Haffkine Institute in Bombay, the Institute’s staff published the following words: “It was with profound regret that Reuter’s message from Lausanne announcing the sudden death of Mons. Haffkine on the 26th October 1930, was received at this Institute. The Haffkine Institute, which owes its present activities to his genius, and the Grant Medical College, which had been the scene of his early researches on plague, were closed down on the 27th of October to pay homage to his memory. Obitu- ary notices have appeared in all our local newspapers and in the medical journals of other countries and these have acclaimed him as one of the greatest bene- factors of mankind. India has special reasons to be- moan his loss; he had spent the best years of his life here fighting against the scourges of cholera and plague; he has saved many of her people from the ravages of these two diseases by his prophylactic inoculations”.(24)

Notes

(1) Selman A. Waksman. The brilliant and tragic life of W. M. W. Haffkine. Bacteriologist Waldemar Mordecai Wolff Haffkine (1860-1930), 1964, Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick New Jersey.

(2) Popovski, M. Sudiba doctora Chavkina (The Fate of Dr. Haffkine). Isdat. Vostochnoi literaturi, 132 pp. Moscow, 1963.

(3) Metchnikoff, Olga. Life of Elie Metchnikoff, 1845–1916. Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston, 1921. Op. cit. Waksman, 1964 p. 9.

(4) Recherches sur l’adaptation au milieu chez les infusoires et les Bactéries. Contribution à l’étude de l’immunité. Ann. Inst. Pasteur 4:363-379, 1890.

(5) Podolsky, E. Waldemar Haffkine and the Plague eliminator. Your Health 5:261–264, 1956. Op. cit. Waksman, 1964, pp. 15-16.

(6) Pasteur, L. Letter to Grancher-Correspondence by R. Vallery-Radot, Vol. IV, pp. 342–344. Flammarion, Paris, 1892.). Op. cit. Waksman, 1964, p. 17

(7) Simpson, W. J. Waldemar Haffkine, C.I.E. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 33:346–348, 1930. Waksman, 1964, pp. 19-20.

(8) Waksman, 1964, p. 28.

(9) Waksman, 1964, p. 28.

(10) Waksman, 1964, p. 31.

(11) Podolsky, E. Waldemar Haffkine and the Plague eliminator. Op. cit. Waksman, 1964, p. 31.

(12) Podolsky, E. Waldemar Haffkine and the Plague eliminator. Op. cit. Waksman, 1964, p. 32.

(13) Waksman, 1964, p. 45.

(14) Waksman, 1964, p. 49.

(15) Waksman, 1964, p. 49.

(16) Waksman, 1964, p. 50.

(17) Waksman, 1964, p. 54.

(18) Waksman, 1964, pp. 54-55.

(19) Waksman, 1964, pp. 57-58.

(20) Sokhey, S. S. The passing of the present plague pandemic in India. In Haffkine Inst. Diamond Jubilee Souvenir Booklet, 1899-1959, pp. 6–11. Bombay. Op.cit. Waksman, 1964, pp. 60-61.

(21) Podolsky, E. Waldemar Haffkine and the Plague eliminator. Op. cit. Waksman, 1964, pp. 69-70.

(22) Podolsky, E. Waldemar Haffkine and the Plague eliminator. Op. cit. Waksman, 1964, p. 76.

(23) Haffkine, W. M. A plea for orthodoxy. Menorah J. 2:67-77, 1916. Op. cit. Waksman, 1964, p. 77.

(24) Waksman, 1964, 81.