The sixth essay in the “Creators” series is dedicated to Tamara Dembo, an outstanding psychologist whose work on the study of “Anger as a dynamic problem” and the rehabilitation of people with disabilities remains scientifically relevant to this day. Dembo was born in Baku, studied with one of the founders of Gestalt psychology, Kurt Lewin, in the 1920s and worked for many years at American universities. In the “Creators” project together with RASA (Russian-American Science Association) T-invariant continues to publish a series of biographical essays about people from the Russian Empire who made significant contributions to world science and technology, about those to whom we owe our new reality.

In the 1920s, an amazingly talented team gathered at the Institute of Psychology in Berlin under the leadership of Kurt Lewin. It also included young girls, emigrants from the Russian Empire. They did a whole series of outstanding works on psychology. And then they dispersed around the world. One of the stars of this team was Tamara Dembo. She completed her most famous work, “Anger as a Dynamic Problem,” when she was a very young researcher. And today psychologists are returning to her works and rethinking them.

Early years. Baku. Russian Empire

Tamara Vasilievna (Wulfovna) Dembo was born in 1902 in Baku into a wealthy Jewish family. Her mother is Sophia Dembo (Volchkina) (1871 – date of death unknown), father – Wulf (Vasily) Dembo (1865 – after 1916).

Wulf Dembo was a co-owner of the oil refining companies “Dembo and Brothers” and “A. Dembo and H. Kagan.” The second company was founded by his grandfather – Tamara Dembo’s great-grandfather – Aron Dembo and Chaim Kagan in 1870 and became a large producer of kerosene.

In early childhood, Tamara Dembo was diagnosed with heart disease. Recalling his long conversations with Dembo already in the second half of the 20th century, American psychologist James V. Wertsch, Tamara Vasilievna’s colleague at Clark University, wrote:

“One of the key constructs Professor Dembo used in her earlier writings on psychological factors associated with successful rehabilitation after illness or injury was “asset-mindedness.” She used this term to refer to the tendency of some individuals to focus on the assets, or strengths, they still possessed, rather than on the overwhelming problems and disabilities that set them apart from others and from their earlier selves.”(1).

Wertsch writes that health problems in childhood largely shaped the professional approach of the future psychologist:

“As is often the case, Professor Dembo’s professional interest in this concept probably has a great deal to do with her own life experience. As a young girl, she was diagnosed as having heart trouble (probably a “heart murmur”) and, as a result, she spent many of her early years confined to her home and often to her bed. She was not allowed to play, go to school (she had a private tutor), or engage in many other activities that are usually so much a part of children’s lives.”

Wertsch writes that already in the second half of the 20th century, Dembo’s childhood illnesses “became a topic of humor among many of her friends.”

Indeed, Dembo lived an unusually long (91 years) life, and not only enjoyed excellent health herself, but also helped rehabilitate many people who were seriously injured during World War II.

The asset-minded principle—focus on what you have and try to forget about what you have lost—was central to Dembo’s life.

By the age of 18, Tamara Dembo not only became physically stronger, but also passed the exams as an external student for a course at the Baku men’s gymnasium. In 1920, she entered the electromechanical department of the Petrograd Polytechnic Institute: she wanted to become an engineer. But there was no time for studying anymore. The revolution and civil war in the Russian Empire forced the Dembo family to emigrate. Wulf Dembo came from Lithuanian Jews. He managed to get Lithuanian passports for the family and in 1921 the Dembos left Russia.

While we know a lot about the life of Tamara Vasilyevna Dembo, almost nothing is known about the fate of her parents. James V. Wertsch writes that most of Dembo’s family died in Germany and the USSR, but does not specify what happened to her father and mother. It is unlikely that their life was easy. This is evidenced, for example, by this episode. When in the early 30s, already in America, Tamara Dembo’s financial situation was simply desperate, a colleague asked her: could her parents help her? And she replied that she had recently sent them every cent. We have not been able to establish what happened to them in Germany after Hitler came to power.

In contrast, the life of Dembo’s companions, the Kagan family, turned out differently. Already in the 21st century, the German writer Verena Dorn wrote a biographical novel about the Kagans (2): “Competing with Nobel and collaborating with Rothschild, Chaim Kagan (1850-1916), a native of a Polish-Lithuanian jewish town, made his fortune in the oil fields of Baku. (And he made his fortune together with his companion, Aron Dembo. – VG) However, the First World War tore the family apart, and the Bolshevik regime destroyed any opportunities for development and prosperity. During these uncertain times, his seven children inherited his business. They fled to Berlin, founded new companies, became global players in the oil business… They ran chains of gas stations and demonstrated an entrepreneurial spirit in an innovative industry of strategic importance. They were philanthropists, helped refugees… and were committed to rebuilding a Jewish homeland in Palestine. When the Nazis came to power, the family, which had established transnational connections, again fled from Berlin to Paris, and from there to Tel Aviv and New York.”

Verena Dorn writes that the Kagans helped refugees. But, apparently, Wolf Dembo’s family was not among those they helped.

Berlin. Golden Twenties

When Tamara Dembo arrived in Berlin in 1921, she was 19 years old. It was an exciting time and an amazing place. The period of the Weimar Republic (1919–1933) was marked by constant social and political conflicts. By the time Hitler came to power in 1933, the government had changed 21 times. But these same years were later called the “golden twenties.” It was a period of technical and cultural innovation, of which Berlin became the European center.

Scientists, writers, musicians and artists from Germany and all over Europe flocked to Berlin. Magnificent orchestras used to sound here, 120 newspapers were established, and 40 theaters used to operate. Among the outstanding writers and scientists who lived in Berlin are Bertolt Brecht and Robert Musil, Albert Einstein and Max Planck. And this was a short time of “Russian Berlin”.

In the early 1920s, a large Russian community settled in Berlin, albeit briefly, schools opened and newspapers were published. For example, the newspaper “Rul” was published here, which was published by the leaders of the Kadet Party Joseph Hessen and Vladimir Dmitrievich Nabokov. The newspaper’s circulation reached 20 thousand. All Russian-speaking Europe read it. It was here that the future great writer Vladimir Nabokov made his debut with his poems. In his novels “Mashenka” and “The Gift,” he described in detail (albeit rather ironically) Berlin in the 20s.

Soviet citizens used to come to Berlin and could freely communicate with emigrants. In fact, due to low prices and a rich cultural life, Berlin for some time became a favorite destination for visitors from the USSR. But not everyone was attracted only by low prices. Soviet scientists and mathematicians, physicists, chemists, and psychologists constantly came to Berlin.

Among the Russian intellectuals who visited Berlin in the early 20s were the psychologists Aleksandr Luria, Lev Vygotsky, and Dmitri Uznadze. Berlin allowed young Tamara Dembo not only to join the turbulent life of the “golden twenties”, but also to establish strong ties with the scientific community, including with American and Soviet colleagues.

Institute of Psychology: Kurt Lewin and his students

Tamara Dembo decides to study at the University of Berlin. The courses she chose are not only characterized by the diversity of her interests, but also by some confusion and uncertainty of choice. She wants to do literally everything: she started with mathematics and natural sciences, then became interested in philosophy, economics and art history. And, finally, psychology, which became her profession.

Dembo first began to study “industrial psychology,” specifically the field we now call ergonomics. But after hearing about Kurt Lewin’s work from her university friends Maria Ovsiankina and Bluma Zeigarnik, Dembo began attending his classes.

At the Institute of Psychology, Levin assembled a group of talented young researchers – male and female. The core of this group were Jewish women, emigrants from the Russian Empire. At first they studied with Levin, and then conducted independent research under his leadership. Like Dembo, Gita Birenbaum, Maria Ovsiankina and Bluma Zeigarnik published the results of their research in the journal ‘Psychologische Forschung’, which was founded in 1921 by leading representatives of Gestalt psychology: Kurt Lewin, Kurt Goldstein, Hans Walter Gruhle, Wolfgang Köhler, Kurt Koffka, and Max Wertheimer(3).

The works of young researchers were published in the journal as part of a long series of publications under the heading “Studies in the Psychology of Action and Affect” under the general editorship of Kurt Lewin.

Kurt Danziger, in his monograph “Constructing the subject: Historical origins of psychological research” (4), writes that the cosmopolitan nature of Kurt Lewin’s group made its members more fully aware of the inclusion of the individual in the social context. They understood better than other psychologists that a person’s behavior is determined not only by the manifestation of his personal qualities, but also necessarily reflects the social situation. They studied man not in isolation, but in a certain psychological field (as Kurt Lewin himself proposed). Accepting this point of view implied a new view of the role of the experimenter and his relationship with the subjects. In short, the experimenter entered into a fairly close relationship with the subject (sometimes quite tense, as in Dembo’s experiments).

Kurt Lewin. Wikipedia

Both Dembo’s training and research took place in the cosmopolitan, truly international atmosphere of Berlin and the Berlin school of Gestalt psychology. The Berlin Institute of Psychology, more than other German research institutes, served as a meeting place for psychologists from all over the world (including the USSR). American psychologist J.F. Brown, for example, assisted Dembo in conducting several of her experiments. Alexsandr Luria also took part in one of Dembo’s experiments as a test subject. (She said later that it was a difficult case). The cosmopolitan atmosphere of the institute may have facilitated Dembo’s adaptation to Berlin and undoubtedly prepared her for future emigration to the United States.

After completing her studies, Dembo began research under the guidance of Lewin and Wolfgang Köhler. From 1925 to 1928, she conducted a series of experiments that eventually became the empirical basis of her dissertation. In this dissertation she mentions Köhler, Lewin, Hans Rupp and Wertheimer as her most important teachers in psychology. But mainly it relied on the principles of Lewin’s topological or field psychology: the design of experiments, the analysis of results, and theoretical understanding reflected Lewin’s dynamic approach of that time.

Before we look in more detail at Dembo’s most famous work, called “Anger as a Dynamic Problem,” let’s briefly talk about the work of her friends: Maria Ovsiankina and Bluma Zeigarnik. These works left a significant mark on world psychological science, and both are associated with Lewin’s ideas, in particular, with the mandatory active interaction of the subject with the experimenter. In these cases (as well as Dembo’s experiments), the experimenter himself seems to play the role of the social context and there are no other influences, that is, in this way a social model is created.

Bluma Zeigarnik’s work is related to the description of the so-called “Zeigarnik effect”. The subject was offered a certain kind of problem, and (s)he began to solve it. In some cases, the experimenter suddenly announced to the subject that (s)he was in a hurry and interrupted the decision. In other cases, the subject calmly brought the decision to completion. After some time, the experimenter asked the subject to remember the problems (s)he solved. In the overwhelming majority of cases, the subject perfectly remembered precisely those tasks that (s)he was not given the opportunity to solve. Zeigarnik showed that unsolved problems remain in the memory, and in some cases this is quite painful.

Ovsiankina’s biographers described the effect named after her as follows: “During the next experiment, the subject received tasks that were elementary in complexity, for example, (s)he was required to put together a figure from divided parts, draw an object, or solve a puzzle. Approximately halfway through the task, the subject was interrupted and asked to perform another action with the words “Please do this.” While the subject was finishing the second task, the experimenter was deliberately distracted by something, for example, writing, looking for papers on the table, or leafing through a book. Having completed the second task, 86% of the subjects returned “to the previous, interrupted action, wanting to complete it, although according to the instructions this was no longer required.” Maria came to the conclusion that an interruption in the implementation of a personally important act leaves a feeling of incompleteness, tension, which prompts a person to resume actions at the next opportunity, that is, an interrupted task, even without stimulating value, causes a “quasi-need.” Thus, the work of M. Rickers-Ovsiankina represented a logical addition and differentiation of the problems of the famous work of Bluma Wulfovna Zeigarnik (the Zeigarnik effect about more durable memorization of interrupted actions than completed ones).” (Female names in psychology: Maria Rickers-Ovsiankina. D. V. Zharova, A. R. Batyrshina. Vestnik of Minin University. 2018. Volume 6. No 1)

The Zeigarnik effect and the Ovsiankina effect became the source of a kind of meme: “unclosed gestalt” and many jokes about it.

Unfortunately, few people today remember the name of the wonderful psychologist Maria Ovsiankina (we plan to devote a separate essay to her in the “Creators” series).

The fates of Zeigarnik and Ovsyankina turned out differently. In the early 30s, Bluma Zeigarnik returned to the Soviet Union. She successfully worked with Lev Vygotsky and Alexsandr Luria. But in 1939, her husband was arrested and sentenced to 10 years in the camps for espionage. He did not return from the camp. The date of death indicated on the death certificate received by the family already in 1990: April 20, 1942. After the arrest of her husband Blum, Zeigarnik was left with two small children.

Maria Ovsiankina emigrated to the USA.

Anger as a dynamic problem

Dembo began her dissertation by outlining her theoretical worldview in a brief introductory chapter. She explained that she wanted to study the origin and development of anger (annoyance, irritation).(5) She argued that the psychology of feelings and emotions is underdeveloped because it is dominated by simple classifications. She explained this shortcoming based on the approach established in psychology. A characteristic of this approach was that researchers observed many people and then attempted to construct an “average subject” based on statistical analysis of associations between specific empirical measures.

Following Lewin, Dembo emphasizes something else: it is necessary to study specific individual cases and their individual development. According to Dembo, instead of “taking an abstract average of as many cases as possible,” researchers should try to reproduce a pure phenomenon under experimental, model conditions.

In this approach, Dembo decides to induce anger in pure laboratory conditions. To do this, Dembo proposed confronting subjects with problems that are either impossible or very difficult to solve, and the experimenter not only records the process, but sometimes actively interferes with the solution of the problem.

During the process of solving problems, the subjects were observed by the experimenter and her assistant. They kept a detailed transcript. After this, the subjects were asked about their feelings during the experiment. Dembo writes that it would be ideal to film the experiments with a movie camera, but tests have shown that this method is still technically too complex and too expensive.

A total of 64 experiments were carried out on 27 subjects (each experiment lasted about one to two hours) over four years (1925-1928). The subjects did not know that anger was the topic of the study.

Dembo used two tasks: “ring throwing” and “flower grasping.” In an experiment with ring throwing, the subject was asked to throw ten rings in a row onto a bottle from a distance of 3.5 m. Most people were unable to do this. In addition, the experimenter sometimes actively interfered with the completion of the task by catching rings thrown by the subject.

In the flower grasping experiment, the task was to reach the flower with the hand without leaving a limited area. Moreover, there were two obvious solutions: kneel down so that your feet remain in the permitted zone and reach the flower, or lean on a chair standing outside the zone and thus reach the flower. But the experimenter insisted on finding a third solution, although there was no such solution, and all proposals from the subjects were rejected as violating the rules of the experiment.

The subjects were engaged in solving problems for an hour or two. They were really tired. And this was also part of the experiment.

Dembo hypothesized that subjects’ repeated failures and provocative behavior by the experimenter (such as ridicule after failure) could lead to anger and irritation.

According to Dembo, analyzing experimental situations, one could assume that the behavior of the subjects is regular, that is, state A always causes state B. But experiments have shown that this is not so. The subject’s condition has a clearly defined accumulative nature depending on the growing stress. If at the beginning of the experiment the subject could simply smile in response to the experimenter’s ridicule, then towards the end he could curse or even throw the ring not at the bottle, but at the experimenter.

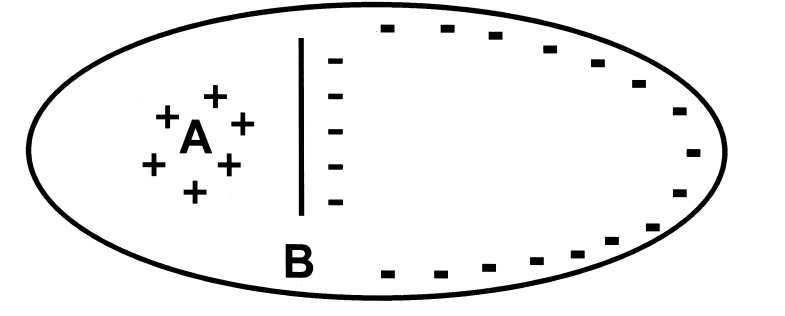

Dembo views the situation according to Kurt Lewin’s topological and vector theories. Several forces (vectors) act on the subject. Moreover, the intensity of these impacts changes.

Diagram of Tamara Dembo’s experiment. Image source: René van der Veer

What are these forces?

First, this is the goal A. For subjects who accepted the experimental conditions, A acquires a sharply positive valence, i.e., the subjects really want to achieve this goal.

Their attempts are thwarted by an internal barrier B, which has a negative valence. When the negative valence of the internal barrier B exceeds the positive valence of the goal A, subjects feel the desire to leave the experiment. However, they almost never do this.

Quitting means, among other things, admitting complete failure. The fact that subjects almost never stop the experiment (i.e., do not leave the room) suggests that there is also an external barrier in the situation – C. (In the figure this is an oval surrounding the experimental field).

The subject in the experiment is squeezed by various forces and barriers. As failures accumulate, tension increases. The subject may begin to “sway”: (s)he oscillates between the desire for a goal and the desire to leave.

Forces are fickle: the subject will feel a stronger attraction to a goal if he decides that the chances of achieving it have somehow become higher.

Much of Dembo’s thesis consisted of detailed descriptions of what subjects do when psychological stress increases. For example, after repeated failures, subjects begin to propose either unrealistic solutions or ersatz solutions. An unrealistic solution: hypnotize a flower so that it flies out of the pot and falls into the hands of the subject. An ersatz solution is, for example, to throw the ring on some other object in the room, and not on the bottle.

Dembo describes a situation where subjects “leave” an experiment without actually leaving the room. Unable to solve the problem and feeling unable to leave the room, some subjects, for example, begin to read the newspaper or daydream. Others try to physically escape the situation, suddenly remembering urgent phone calls they need to make. The experimenter’s harsh position (for example, “We must continue the experiment,” “There is another solution”) ultimately forces almost all subjects to renew their efforts.

For the subject’s self-esteem, it is vital to hide his feelings, to pretend that he is actually calm and does not care too much about the process of solving the problem. In Dembo’s terms, subjects encapsulate their state, creating a barrier between the internal mental system and the external Umwelt (that is, the environment directly interacting with the subject).

But the growing tension also puts pressure on this internal barrier, and, in the end, only a small push from the experimenter is enough (for example, ridicule when the subject’s next attempt to solve a problem fails) for the subject to break: the barrier between the internal system and the outside world disintegrates , the subject becomes extremely emotional and rude, he begins to talk about his personal affairs and become completely childish.

We can say that Dembo in her work analyzed the behavior of the subjects from the point of view of a complex dynamic system of field forces and barriers.

The intensity of these forces and the resistance of the barriers change over time, so statements like “environmental stimulus A will always be followed by response B” are simply not true.

By creating adequate conditions, manipulating and provoking subjects, Dembo

was able to expose the psychological mechanism of the development of anger. She argued that the ideas she gained from the experiment were applicable in real-life situations.

René van der Veer, outlining Dembo’s experiment, notes that the analysis of the experimental situation and the behavior of the subjects in Dembo’s work was carried out in the tradition of Lewin’s vector psychology. When she began her pilot experiments in the summer of 1925, this conceptual apparatus did not yet exist, but when analyzing the results, five years later, she could already use vector theory. It is possible that her experiment, which she discussed many times with her supervisor, also influenced the development of the concepts of this Lewin theory.

While Dembo was preparing her dissertation with Kurt Lewin, she also managed to work in the Netherlands, where she conducted experiments on rats with Professor Frederik J. J. Buytendijk. She writes to Buytendijk: “Mr. Professor, you were not entirely mistaken when you suspected that I was sick. In fact, I have a fever, and this fever will continue for another 7 weeks… until the examination.” (6) With these words, written on May 31, 1930, Dembo jokingly spoke about the defense of her dissertation, which was scheduled for July 25 of the same year.

Dembo successfully defended her dissertation. Kurt Lewin praised it as “valde laudabile” (very commendable). Although this is not the highest rating (the highest is “eximium” – “excellent”), Dembo was not upset. Two days later, she happily reported the defense to Buytendijk: “A few days ago I successfully defended my dissertation and I feel like a big weight has been lifted off my shoulders. I hate exams and hope that I never have to take them again in my life. But all’s well that ends well. It’s also nice that after the exam I will immediately be very busy. In 6 weeks I’m going to see Professor Koffke in Northampton, and before that I need to prepare an essay for publication, I need to “restore” my English, see something in Berlin and prepare everything for the trip. I’ll go via Hoek van Holland, London, Liverpool… and hope to be in New York on September 22nd; From there it’s only 4 hours to Smith College” (7)

The situation in Germany became increasingly tense. Berlin in 1931 was very different from Berlin in 1921, where Dembo arrived from Russia. But moving to the United States was not an escape from imminent danger, from the power of the Nazis (judging by Dembo’s letters, she did not feel anything like that). On the contrary, Dembo saw working in the United States as an excellent chance to further her career.

USA. Academic Nomad

Thus ended the European period of Tamara Dembo. She visited Europe from time to time, but continued her academic career in the United States, first at Smith College with Kurt Koffka, then at Worcester State Hospital (1932–1934). But life was not easy.

Koffka writes to Molly Harrower, who worked in London in 1933-1934:

“My beloved [referring to Molly Harrower, age 27, lecturing at London University in 1933–34], Friday night after a very spirited seminar in which I talked a great deal, I drove home with Dembo by way of my garage. I inquired about her prospects & found

they are absolutely tragic. Some weeks ago she & Hanfmann (8) had been told that they would be able to continue for another year on the same terms as this. Since then two patients of the hospital have committed suicide & one has murdered an attendant which brought the terrible situation of an understaffed institution to the authorities. They had directed some of their funds for research work, but now this money will be, quite legitimately, returned to the fund for attendants. So the best that can happen to the two girls is that they are kept on for board & lodging without a cent of salary. When I asked Dembo whether she would get some money from her parents she answered without embarrassment that not only was this out of the question, but that during this year she had to send every penny she could spare to them. So she has not a cent saved! And then, you know, she has no prospect of her position ever improving, since she is here on a student’s visa & therefore unable to accept any paid position even if she could get one. She never

complains but shows the most admirable courage. But I feel that something should be done to help her. Do you think she could get anything in England, say in a private school as teacher of Germany with the chance of earning some extra money by giving private Russian lessons?

I thought you might know of something. And you are always willing to help other people. So you will forgive me for asking a new favor from you. (pp. 169, 173)” (9)

But the situation improved thanks to Koffka’s care, and because Dembo’s teacher, Kurt Lewin, emigrated to the United States. He left almost immediately after Hitler came to power. Dembo subsequently worked with Lewin at the University of Iowa and Cornell University (1934–1936). He and his wife treated Dembo like a daughter.

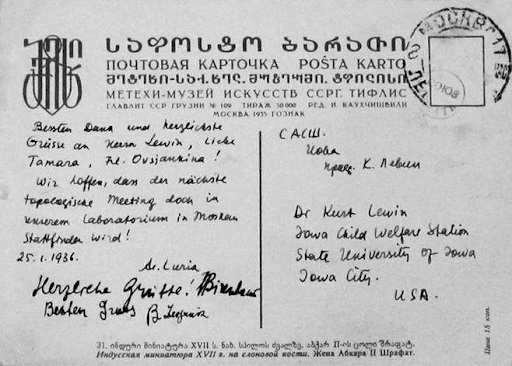

Postcard in German dated January 25, 1936, signed by Alexsandr Luria, Gita Birenbaum and Bluma Zeigarnik. It is addressed to Kurt Lewin, Tamara Dembo and Maria Ovsiankina. The postcard was sent from Moscow to the USA to Lewin’s university address (Kurt Lewin Archive) on January 25, 1936. Luria, Birenbaum and Zeigarnik propose to hold the next “Topological Meeting” (a conference on Kurt Lewin’s topological psychology) in their laboratory in Moscow. The idea initially seemed almost like a joke, but on February 20, 1936, Luria sent another letter to Levin, which emphasized that personality research conducted in Moscow in the spirit of Levin’s “dynamic theory” was developing every year. Luria mentioned the clinical work of Birenbaum and Zeigarnik and their upcoming major study on cognition and affect. Then Luria proposed holding a large conference – the Levin Symposium – not in Moscow, but in Kharkov in June 1936. But the Iron Curtain was quickly falling, and these plans were not destined to come true.(10)

TheTopological Group in 1935. Archive of the History of American Psychology. Tamara Dembo is (presumably) standing fourth from left in the front row. (11)

Dembo worked at Stanford University (1945-1948), where she worked on the rehabilitation of military personnel who were seriously injured during World War II. Then there was Harvard University (1951–1953), where Dembo conducted research on American Jewish communities. Of course, these are very prestigious universities, but Dembo had short temporary positions everywhere.

Until she found her university: Clark University in Massachusetts in Worcester. She seemed to describe a twenty-year circle around America and returned to her harbor in 1953. She received a permanent position at Clark University, although not immediately, but only in 1959.

She continued her research. Books and large articles were published, for example, “Adjustment to misfortune – A problem of social psychological rehabilitation,” in which she and her colleagues summarized their experience in the rehabilitation of military invalids. (12)

A department photograph shows Tamara Dembo, Seymour Wapner, John Bell, two unidentified men, and Heinz Werner in the 1950s. Courtesy of Clark University Archives. (13)

Dembo worked at Clark University until her retirement in 1972, but after that she remained an Emeritus Professor and lived on the university campus. She maintained the closest professional and friendly connections with university psychologists.

Tamara Dembo lived a great life. And almost half of this life was spent in Worcester. Little did she think in 1952, when she arrived to take up her next temporary position, that she would remain at Clark University forever.

Testament of a Gestalt psychologist

When Tamara Dembo passed away, her colleagues said goodbye to her with dignity. In the Journal of Russian & East European Psychology (it was founded back in 1962 and is still published) published Dembo’s large work “Thoughts on Qualitative Determinants in Psychology”. Psychologists Alberto Rosa and James V. Wertsch wrote a lengthy review of this work. And James V. Wertsch published In Memoriam (we began our essay with quotes from this article). (14)

Alberto Rosa and James V. Wertsch writes: “In Dembo’s view, the possibilities for studying human experience using the scientific methods typically employed in psychology are very limited at best. Instead of relying on “objective observations by outsiders,” she argues that it is essential to shift to experiential observations available only to the bearer of the experience. Among other things, this suggests transformation of the relationship between psychologist and subject, and this is one of the most interesting and far-reaching implications of Dembo’s article…

The origins of this line of reasoning can be found in Dembo’s 193 1 article on anger, in which, as an experimenter, she engaged subjects in intense social interaction rather than viewing them from the outside; but the kind of relationship of equality she envisions in her present article goes beyond that. It involves a transition from a relationship between an experimenter as subject (i.e., “subject” in a different sense than normally encountered in psychology) and an object (the “subject” in psychological research) to a relationship between two genuine subjects. In certain intriguing respects, this is similar to the innovation Bakhtin… saw Dostoevsky producing in novelistic discourse. In both cases a transition from a kind of I-she/he relationship to an I-I relationship is involved. This, of course, constitutes a radical departure from business as usual in research psychology. In addition to its implications for the methods of research psychology, this has implications for understanding psychology as a political activity. Dembo’s proposals are proposals for injecting new politics into the process of doing psychological research. Specifically, this is new politics in which the differences in power and authority between experimenter and “subject” are reduced, if not eliminated. This bold step reflects a wisdom accumulated through nearly a century of personal and professional experience. It is worth listening to.” (15)

The research is ongoing. Gestalt is open.

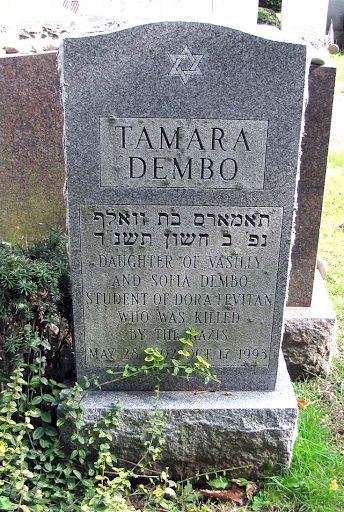

Monument at the grave of Tamara Dembo

Tamara Dembo had neither a family nor children.

She passed away on October 17, 1993. The New York Times published (16) a short obituary noting Tamara Dembo’s work in rehabilitating wounded World War II veterans.

Tamara Dembo is buried in B’nai B’rith Jewish Cemetery, Worcester, Massachusetts.

Her monument is inscribed with her name in Hebrew and English and the dates of her life. “Tamara Dembo is the daughter of Vasily and Sophia Dembo. A student of Dora Levitan, who was killed by the Nazis.” Who Dora Levitan is and what role she played in the life of the outstanding Gestalt psychologist could not be established.

Notes

(1) James V. Wertsch (1993) In Memoriam, Journal of Russian & East European Psychology, 31:6, 3-4. To link to this article:

http://dx.doi.org/10.2753/RPO1061-040531063.

(2) Verena Dohrn. “Die Kahans aus Baku: Eine Familienbiographie”.

(3) The journal is still published today, although in English under the name Psychological Research.

4) Danziger, K. (1990). Constructing the subject: Historical origins of psychological research. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge, University Press. (1990)

(5) In presenting the work of Tamara Dembo, we will follow the article by René van der Veer. Tamara Dembo’s European years: working with lewin and Buytendijk. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences: Vol. 36(2), 109–126. Spring 2000. Tamara Dembo’s dissertation was published in the journal and almost immediately came out as a monograph: Der Ärger als dynamisches Problem. Psychologische Forschung, 15, 1–144. Der Ärger als dynamisches Problem. Berlin: Julius Springer.

(6) René van der Veer.

(7) René van der Veer.

(8) Eugenia Hanfmann (1905-1983) – psychologist, emigrant from Russia. She and Dembo both worked together and shared a room in Worcester

(9) Quote. by William R. Woodward. Russian women emigrées in psychology: Informal Jewish Networks. History of Psychology 2010, Vol. 13, No. 2, 111–137. University of New Hampshire.

(10) Revisionist Revolution in Vygotsky Studies. Edited by Anton Yasnitsky and René van der Veer. First published 2016. Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group. London and New York, NY 10017, p. 211

(11) William R. Woodward.

(12) See Dembo, T., Leviton, G. L., & Wright, B. A. (1956). Adjustment to misfortune — A problem of social psychological rehabilitation. Artificial Limbs, 3, 4–62.

(13) William R. Woodward.

(14) Thoughts on Qualitative Determinants in Psychology. Tamara Dembo

To cite this article: Tamara Dembo (1993) Thoughts on Qualitative Determinants in

Psychology, Journal of Russian & East European Psychology, 31:6, 15-70

http://dx.doi.org/10.2753/RPO1061-0405310615

Tamara Dembo and Her Work. Alberto Rosa, James V. Wertsch. To cite this article: Alberto Rosa & James V. Wertsch (1993) Tamara Dembo and Her Work, Journal of Russian & East European Psychology, 31:6, 5-13 http://dx.doi.org/10.2753/RPO1061-040531065</ a>

Journal of Russian and East European Psychology, In Memoriam. James V. Wertsch

To cite this article: James V. Wertsch (1993) In Memoriam, Journal of Russian & East European. Psychology, 31:6, 3-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.2753/RPO1061-040531063.

(15) Tamara Dembo and Her Work. Alberto Rosa & James V. Wertsch.

(16) Tamara Dembo, 91, Gestalt Psychologist Who Studied Anger. New York Times, 1993.10.19.