T-invariant, co-founder of Dissernet Andrey Rostovtsev and community project coordinator Larisa Melikhova continue their “Plagiarism Navigator”. Through individual cases of international academic plagiarism, we examine the global-scale imitation of scholarly activity. To tackle this issue, specially trained NLP language models—developed in collaboration with linguists from the universities of Helsinki and Oslo—are employed. In the fifth installment, we examine the case of Andriy Vitrenko, Ukraine’s Deputy Minister of Education and Science, whose dissertation and academic papers have been flagged for plagiarism.

Previously in Plagiarism Navigator

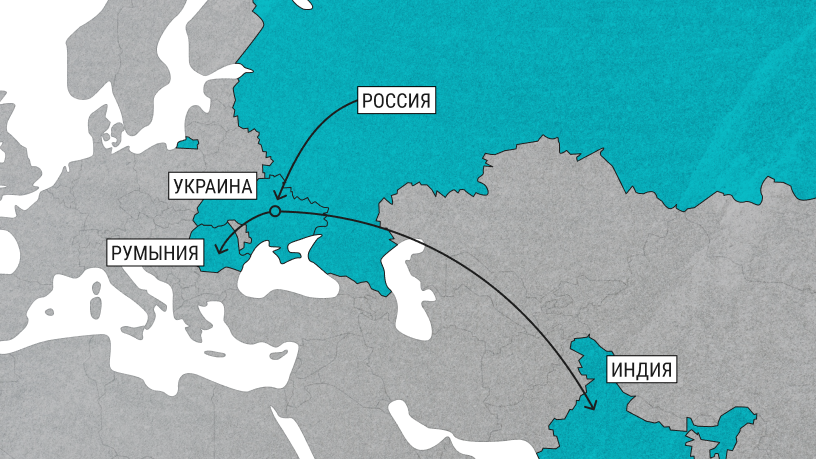

- Episode 1: China-Ukraine-Poland – The story of a Chinese scholar who defended a dissertation in Kharkiv, cobbled together from Russian-language works translated into Ukrainian.

- Episode 2: Russia-Tajikistan-Iran – The case of Iranian scholars obtained degrees in Tajikistan (2011–2013) under Russia’s VAK system.

- Episode 3: Russia-Serbia-Turkey-Switzerland-Lithuania – The tale of a Serbian academic who resorted to buying co-authorships and outright plagiarism.

- Episode 4: Russia-USA-Brazil-UK-Switzerland-India – A professor at Sechenov University who infiltrated an Iran-Iraq publication scheme in top Western journals, creating a lucrative paper mill within his own institution.

This investigation builds on the work of our Ukrainian colleagues from the Dysergate initiative. Detailed reports on this and other plagiarism cases in Ukraine are available on the platform “Plagiarism and Fraud in Academic Works.” Today’s subject is Andriy Vitenko, Ukraine’s Deputy Minister of Education and Science. Yet this comes as no surprise—we have long documented how post-Soviet states inherited and perpetuated fraudulent academic practices from the USSR. The vast reservoir of Russian-language texts serves as an inexhaustible source for translated plagiarism, particularly convenient given the linguistic proximity of these languages.

BACKGROUND

Andriy Vitrenko was born in 1977, Vitrenko graduated from Kyiv National University of Trade and Economics and later worked at Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv (KNU). He earned a Candidate of Sciences (PhD) in Economics in 2005 and a Doctor of Sciences in 2017. Since 2020, he has served as Ukraine’s Deputy Minister of Education and Science and as a Kyiv city councilman for the “Servant of the People” party.

Dissertations

The candidate’s dissertation by Vitrenko, titled “The Market of Advertising Services in a Transitional Economy” (available on the National Repository of Academic Texts), contains a substantial segment—approximately twenty pages—that is nearly verbatim copied from two Russian-language candidate’s dissertations and translated into Ukrainian.

The first source is Smirnova L.A.’s “Study of the Structure and Management of the Advertising Services Market,” defended in St. Petersburg in 1999. The second is Vechkinzova E.A.’s “Formation and Development of the Advertising Market in a Transitional Economy (Based on Materials from the Republic of Kazakhstan),” defended in Novosibirsk in 2001. Vitrenko’s text makes no mention of either dissertation.

The copied passages from Smirnova’s work retain numerous introductory phrases, such as: “in our opinion,” “we believe,” “from this, we can conclude,” “the subject of our study,” etc. The adaptation of Vechkinzova’s dissertation proved more challenging: since her research focused on Kazakhstan, the text underwent “creative revision”—a common practice in such cases, as Dissernet has documented many times. For instance, this immediately brings to mind the case of a rector of Yakutsk University who replaced references to Kaliningrad Oblast with the Republic of Sakha in her dissertation.

Expected substitutions in Vitrenko’s dissertation include:

the economy of Kazakhstan <—> the economy of Ukraine

republic, region <—> country

Kazakhstani producers (users) <—> Ukrainian producers (users)

Karaganda Oblast <—>Ukraine

An obvious falsification involves replacing a company’s name while keeping the numerical data unchanged:

“According to research firm Web Track, the most popular types of advertising on the global computer network are as follows: computer hardware and software—28%, communications business—11.5%…” <—> “According to analytical websites www.yandex.ru and www.bigmir.net, the most popular types of advertising on the global computer network are as follows: computer hardware and software—28%, communications business—11.5%…”

Another striking example occurs when the text references a specific Kazakhstani enterprise:

“In 1999, “JSC Karaganda-Nan” conducted active PR efforts throughout the year.” <—> “In 2002, leading Ukrainian alcohol producers conducted active PR efforts.”

As seen here, the year was also conveniently “refreshed”— it would hardly do in 2005 to cite data from 1999. Meanwhile, in another section, the “study period” was significantly extended:

“Throughout the study period from 1997 to 1999…” <—> “Throughout the study period from 1991 to 2002…”

It remains unclear why, in the current deputy minister’s view, the development of advertising in Ukraine took significantly longer than in Kazakhstan (11 years instead of three). Yet, all the results, trends, and forecasts of the purported original research turned out to be identical to those from Kazakhstan. The only difference was the exclusion of one prediction: “the emergence of new advertising services involving printed advertisements on polyethylene bags, mugs, boxes, and wrapping paper,” which E.A. Vechkinzova had forecast for Kazakhstan in 2001. Andriy Vitrenko, however, omitted this for his 2005 study on Ukraine.

Instead, he retained verbatim the concluding statement lifted from Vechkinzova’s dissertation: “Advertising is crucial for the economy, relevant to society, and undoubtedly an interesting subject for academic research.” This was the “groundbreaking” insight that the newly minted advertising specialist proved—seven years later—by publishing two more plagiarized fragments from the same dissertations under his own name in the Bulletin of Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv (KNU).

Publications

At the time of this investigation, the deputy minister had six articles published in international academic journals—all of which contained extensive improper borrowing.

In 2012, while still a PhD holder and associate professor at Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, he published two Ukrainian-language articles in the KNU Bulletin (Economics Series). The first, “The Socio-Economic Significance of Modern Advertising and Advertising Activities,” replicates a section from Smirnova’s dissertation. The second, “The Evolution of Theoretical Understanding of Advertising Across Economic Schools and Their Distinct Perspectives,” is copied from Vechkinzova’s work. In other words, the future doctor of sciences and deputy minister had yet to produce anything original: one piece was plagiarized from a Russian dissertation, while the other merely substituted “Kazakhstan” with “Ukraine,” lifted from research about Kazakhstan.

The only notable detail—if it can be called that—was the inclusion of nine English-language sources in the first article’s bibliography (copied directly from Smirnova’s dissertation). This resulted in a 2012 paper on modern advertising citing exclusively works from 1964 to 1988. Strangely, neither the KNU Bulletin’s editorial board nor the peer reviewers (assuming there were any) found this discrepancy worth questioning.

Follow us on Social Media

In 2016, Vitrenko published articles in two Romanian journals, both focusing on the service sector—a key theme of his future doctoral research. These publications were essentially English translations of large portions of text lifted from two unrelated Russian doctoral dissertations.

The article “Theoretical Comparative Analysis of “A Good” and “A Service” as Base Economic Theory’s Categories” (Studia Securitatis) copies extensively from Sofina T.N.’s 1999 dissertation “The Service Market: Methodological Foundations of Formation and Functioning” (defended in St. Petersburg). Apparently, Vitrenko assumed that the service sector had remained unchanged for nearly two decades—or that Ukraine lagged behind Russia by exactly 17 years. While he omitted a Marx quote from the original Russian text, he forgot to replace “Russia” with “Ukraine” in one critical passage. Thus, an article supposedly about Ukraine abruptly declares: “Issues of social security in Russia still remain underexplored, both in theory and practice.”

The second article, “Service Sector in the Structure of the National Economy of Ukraine: Features, Dynamics and Main Trends” (Revista Economica), translates chunks of Makhasheva S.A.’s 2009 dissertation “The Service Sector and the Formation of a New Architecture for Regional Socio-Economic Systems” (defended in Nalchik). This time, Vitrenko was more meticulous in substitutions:

Russia <—> Ukraine

Russian companies <—> Ukrainian service sector

Economy of Russia <—> Ukrainian economy

Russian service market <—> Ukrainian service market

Yet the core analysis, structure, and even regional case studies (now rebranded as Ukrainian) remained unchanged.

By 2020, now a Doctor of Sciences and still an associate professor at Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv (KNU)—while also serving as Deputy Dean for Research and International Cooperation at the Faculty of Economics—Vitrenko co-authored two articles on enterprise management. These were published in Indian journals under IAEME, one of the world’s largest open-access academic publishers.

The article “Comprehensive System of Financial and Economic Security of the Enterprise”, published in International Journal of Management, boasts six co-authors—all candidates or doctors of economic sciences from six different Ukrainian cities: Vitrenko A.A. (Kyiv), Stashchuk E.V. (Lutsk), Kuzmenko O.V. (Dnipro), Kopteva A.N. (Kharkiv), Tarasova E.V. (Odesa), Dovhan L.P. (Irpin). How did these researchers collaborate? Despite thorough searches, no prior joint publications, conference appearances, or academic connections between them could be found. Such short-lived, geographically dispersed collaborations are a hallmark of “authorship-for-sale” schemes—where researchers pay to be listed as co-authors without contributing to the work. In a previous Plagiarism Navigator report, we exposed three such “publication marketplaces”, but the true number is certainly higher.

One of the reasons behind the popularity of these “paper mills” is that detecting purchased publications is inherently difficult—we can only infer co-authorship transactions based on indirect evidence. However, Ukrainian researchers have reliably documented at least one verifiable case: the publication involving Vitrenko drew heavily from a Russian textbook on management theory published 11 years earlier in Moscow—specifically, Dmitry A. Novikov’s Theory of Educational Systems Management (2009). This instance is noteworthy precisely because it is so rare: purchased articles typically do not contain overt plagiarism. In fact, International Publisher—a company linked to hundreds of paid publications listed on Dissernet—explicitly states, “Our articles are plagiarism-free!” And, based on our observations, this claim holds true. Their product is indeed original—it simply has no connection to the alleged “authors” who reap academic recognition and dividends from texts they did not write.

The article under scrutiny, co-authored by Vitrenko, exhibits classic plagiarism: illustrations are copied directly from the source material (with translated text), and references are falsified. The International Journal of Management appears to be a favorite among Ukrainian plagiarists—thanks to investigations by colleagues, this marks the third problematic publication by Ukrainian authors in the same journal. Each case follows a similar pattern: a large, heterogeneous group of co-authors and improper borrowings from Russian-language sources, rendered in English translation.

Vitrenko’s second article,“Features of Internationalization of SMEs Under the Influence of the Institutional Environment” (International Journal of Advanced Research in Engineering and Technology, 2020), mirrors the previous case. It features six co-authors from different Ukrainian cities (likely the journal’s maximum allowed), with no overlap between the two teams except Vitrenko. The co-authors, again, share no prior collaborative work—though their credentials appear more distinguished: Tarasuk H.N. (Dean), Basyurkina N.I. (Department Head), Shlapak A.V. (then Deputy Department Head, now Vice-Rector and Kyiv City Council deputy for Batkivshchyna), Berezhnytska U.B. (Department Head), Kosychenko I.I. (the sole junior researcher, a PhD student at the time).

The paper lifts its content from Tatyana Tsukanova’s 2015 dissertation, “Internationalization of Russian Small and Medium-Sized Businesses: The Role of the Institutional Environment” (defended in St. Petersburg). Beyond verbatim text copying, the article reproduces Tsukanova’s illustrations, diagrams, and tables—creatively “adapted” through translation, minor rearrangements, and the merging of two tables into one. Notably, the modified table falsifies data: results for Russian businesses are relabeled as Ukrainian.

Europe has seen its share of high-profile plagiarism scandals, with ministers in Austria, Germany, and Norway resigning over such allegations in recent years. In Ukraine, this is already the fifth major plagiarism scandal involving senior officials. Notably, both Ministers of Education and Science under whom Vitrenko served as deputy were accused of dissertation plagiarism. Oksen Lisovyi, the current minister, voluntarily relinquished his academic degree in May 2023, halting a formal plagiarism review. Serhiy Shkarlet, his predecessor, faced a 2024 ruling by the National Agency for Higher Education Quality urging the ministry to revoke his doctorate—though Kyiv’s Administrative Court later overturned the plagiarism verdict. (Shkarlet denies any wrongdoing.)

The question now is how the case against Andriy Vitrenko will unfold.