After Donald Trump’s inauguration as president, there was talk of rebooting U.S.–Russian cooperation across many fields — space included. In Moscow, hopes were pinned on the “Luna” program, anticipating that it could be pursued jointly with the US program, ideally as a joint venture with the United States. Is there any real future for U.S.–Russian cooperation in space? And could Russia’s lunar program plausibly be its centerpiece? Vadim Lukashevich, an aerospace expert, takes stock.

In April 2014, a joint Roscosmos and Russian Academy of Sciences working group proposed a lunar exploration roadmap (LP‑2014) to be folded into the Russian Federal Space Program for 2016–2025 (FSP‑2016–2025). The plan envisioned three phases on the lunar surface, beginning with a scientific outpost that would, through research and the gradual build‑out of power, life‑support, lab modules, and transport, evolve into a crewed base. Phase one (2016–2028) called for two landers (“Luna-25” and “Luna-27”), one orbiter (“Luna-26”), and a sample‑return mission (“Luna-28”). Phase two (2028–2030) forecast crewed operations in cislunar space using a next‑generation transport vehicle, alongside continued use of automated stations in lunar orbit and on the surface. On the third phase, from 2030 onward, the plan anticipated cosmonaut landings near the outpost and the first base infrastructure, with completion targeted around 2040.

T-INVARIANT REFERENCE

Vadim Lukashevich

Born 1963. Candidate of Technical Sciences. From 1985 to 1992, designer at the Sukhoi Design Bureau; contributed to the carrier-based fighter Su‑33 (Su‑27K) and the multirole fighter Su‑35 (Su‑27M). From 2011 to 2015, expert in the Skolkovo Foundation’s space cluster. Author on space and aviation in Russian and international media.

LP‑2014 required a whole family of new space systems. The next‑generation crewed vehicle (then known as PTK‑NP, later renamed Orel) would be the workhorse for phases two and three, launched atop new rockets. Flight‑test campaigns in low Earth orbit were slated to start in 2024, with a first crewed lunar mission penciled in for 2028. The Angara‑A5 rocket could loft the vehicle to LEO, but lunar missions demanded a super‑heavy launcher, as the lunar variant with its upper stage (PTK‑L) was expected to mass around 90 tons in parking orbit. The plan also called for two interorbital tugs of different classes and three reusable lunar lander complexes for surface operations. Phase two extended beyond FSP‑2016–2025, so development of the critical systems — chiefly the super‑heavy rocket — was to begin immediately; the program request for 2016–2025 was 28.5 billion rubles (roughly $800 million at mid‑2014 rates).

Russia’s 2014 lunar program was drafted in 2013, before Russia’s aggression against Ukraine and the ensuing sanctions, so the plan assumed broad international cooperation. If partnership with NASA continued, joint work in lunar orbit was seen as feasible as early as 2024 — for example, during PTK‑L flights to the Earth–Moon L2 point. Russia expected to contribute key capabilities for deep‑space crewed flight: the PTK‑L transport, a super‑heavy launcher, and a long‑duration habitable module. Russian expertise in building pressurized modules was touted as a unique strength that, together with the new spacecraft and rocket, could position Moscow for a strategically useful role in an international lunar effort.

Top news on scientists’ work and experiences during the war, along with videos and infographics — subscribe to the T-invariant Telegram channel.

It also mattered that LP‑2014 rested primarily on Russia’s own scientific, technical, and financial resources, treating foreign cooperation as a force multiplier keeping Roscosmos in the lead. Had LP‑2014 been executed and the systems delivered, Russia would indeed have been an attractive partner with something real to bring to the table.

Eleven years on, both Russia’s space sector and the country as a whole look very different. The FSP‑2016–2025 was adopted in drastically pared‑down form. Scientific and technological decline continued. Development of the new crewed ship slowed markedly and ran into hard engineering problems. Flight‑test campaigns still have not begun; the first uncrewed flight is now planned “no earlier than 2027” with the modified Angara‑A5M launcher — itself still under development. Work on the Yenisei super‑heavy launcher reached preliminary design approval but was effectively frozen by late 2023 due to lack of funding, pushing any crewed lunar flight into the 2030s. In November 2024, Roscosmos signaled that the approved Yenisei preliminary design would be refined during the technical design phase, and that crewed lunar flights were being postponed. Consequently, the now-unnecessary lunar PTK-L spacecraft is slipping as well. In fact, phases two and three have been shelved. What remains is the phase‑one slate of four automated missions.

The first of those, Luna‑25 — which cost 12.6 billion rubles (120 to 400 million USD depending on the exchange rate) — finally launched on August 11, 2023 after years of delay. It failed ignominiously eight days later, crashing into the Moon during descent after a faulty braking burn. What’s left on paper are Luna‑26 (nominally 2027) and Luna‑27 and Luna‑28 sometime after 2030 — i.e., beyond any realistic planning horizon. At this tempo, talk of a Russian cosmonauts on the Moon by 2040 sounds about as plausible as sending a crew to Alpha Centauri by 2060.

As things stand, Russia has little compelling to offer prospective partners for lunar exploration — whether in research or operations. That does not mean Russia isn’t eager to cooperate; it is, precisely because it has no practical path to reach the Moon on its own. The posture has shifted from “let’s go together” to the more plaintive “please, take us with you.” Where equal partnership was once imaginable, Russia now needs outside resources to salvage its plans — a shift that makes it a liability rather than an asset and renders any cooperation largely political.

Which brings us to politics, the real driver of lunar programs for major space powers, above all the United States and China. Moscow stated this political motivation plainly in its November 2018 “Concept of the Russian Comprehensive Program for Lunar Research and Development”: the strategic goal of lunar programs for world powers is to secure their national interests on a new space frontier. By the mid‑21st century, a lunar base may become a necessary element of strategic parity among leading global powers. In other words, nuclear weapons alone won’t keep you in the first tier; you will also need a presence on the Moon. Because Russia cannot achieve that on its own, it must try to do so with someone else paying part of the bill.

Partners, however, are chosen on Earth. Spaceflight is a tool for earthly aims in a new environment, so space partnerships are feasible only with allies. Competition on Earth among nations (or blocs) begets competition in space, including on the Moon), making partner selection always driven by long-term political considerations. When discussing potential resumption of U.S.–Russian space cooperation, several points should be considered.

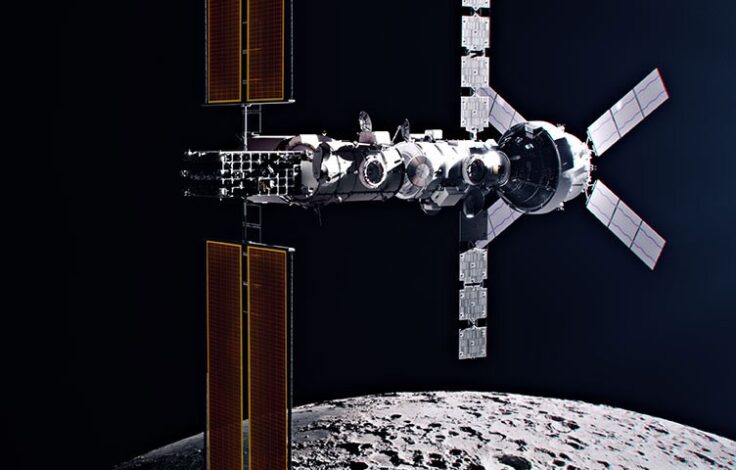

First, with the practical absence of a viable national space program culminating in a Moon landing, Russia simply has nothing to offer the United States, which is pushing ahead on two fronts: the cislunar Gateway station and lunar landings under the Artemis program. Both have moved into hard‑ware: Gateway habitable modules are in manufacture; Orion and the SLS super‑heavy have already flown; and SpaceX’s super‑heavy Starship is deep into flight tests, with ambitions extending from the Moon to Mars.

Second, Russia’s current space capabilities are substantially — by roughly an order of magnitude — below those of the United States. Mutually beneficial cooperation is possible only between roughly equal partners that can exchange equipment, technologies, achievements, expertise, and experience. Each side contributes what it has and receives what it needs. For example, during the Shuttle–Mir program (1995–1998), U.S. shuttles serviced the Russian Mir complex, delivering crew and cargo while the Americans gained Soviet‑Russian expertise in long‑duration spaceflight. Another example is the International Space Station (ISS). At the time, the USSR was developing the large orbital complex Mir‑2, while the United States pursued the large orbital station Freedom. Both projects were extremely costly but made strategic sense during US–Soviet competition. After the USSR’s collapse, Mir‑2 proved beyond Russia’s means, and for the United States, building Freedom became unjustifiable without a geopolitical rival. At that historical juncture, Russian and American interests aligned, and the decision was made to combine each side’s developments into a single international station built from two segments — an American (with Western partners) segment and a Russian segment. That ISS collaboration allowed costs to be shared and, through synergy, let each side achieve what it had originally planned for national stations. Today, reproducing this model for a lunar program is impossible given the parties’ asymmetric capabilities. Russia’s realistic option is to attach itself to a serious partner that can, figuratively, tow it to the Moon.

Up-to-date videos on science during wartime, interviews, podcasts, and streams with prominent scientists — subscribe to the T-invariant YouTube channel!

Third, political risks must be factored in. Any long‑term program — especially one involving Moon landings — implies close, sensitive cooperation over 15–20 years or more. Such projects are feasible only between partners who have confidence in one another for the long haul. Russia cannot be confident in the United States because presidential turnover every four years often brings policy shifts or program cancellations. Recall George W. Bush’s Mars initiative or Barack Obama’s Constellation program: both were launched with fanfare by one administration and later unceremoniously canceled by another. Returning to the White House for a second term, Donald Trump has announced intentions to cut NASA’s budget by a quarter and reduce (or even terminate after the next two Orion flights to the Moon) the Artemis program, tied to the cislunar Gateway station. Even current American partners in these programs, already committed to manufacturing flight‑ready habitable modules, have reasonable doubts about the U.S.’s ability to sustain long‑term obligations. What, then, can be said about cooperation between adversaries like the U.S. and Russia? In the first half of 2025, Trump made gestures toward Moscow, but what will happen in four years is unknown. For Russia to rely on long‑term U.S. cooperation under these conditions is risky; it may pursue short‑term gains in hopes that the next administration won’t revoke them right away.

On the other hand, any short‑term thaw is tied closely to Trump and is likely to reverse once he leaves office. Russia’s fundamental properties that surfaced in 2014 over its actions in Ukraine will not disappear. And given Russia’s strategic partnership with China, the United States has even less reason to trust Moscow over the long term. This is why Russia has turned more toward a “politically aligned” China, with which it signed a 2024 agreement on cooperation to develop the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) on the Moon’s surface.

Fourth, Russia’s space ambitions themselves become an obstacle to American cooperation. Over the past two decades, Russia has behaved like a capricious, jealous, and unpredictable child with inflated self-esteem, while the gap between ambitions and capacity widens. A stark example was Russia’s 2018 exit from the Gateway project. Under a 2017 joint statement, Russia was to develop an airlock module for Gateway; a year later, it declared that “Moscow is dissatisfied with participating in the American project in its current form in a secondary role.” The issue was that, unlike the ISS — where American and Russian segments were built to national standards and joined in low Earth orbit only via transition interfaces — Gateway asked Russia to build a single module to U.S. specifications. But how could the homeland of Sputnik, Gagarin, and Tereshkova — the nation that opened the path to space for humanity — build something to foreign standards and norms? Meanwhile, Roscosmos was undeterred by the fact that, even after building, the airlock couldn’t be delivered to cislunar orbit independently, and it would fly there on an American launcher from an American spaceport. Including a Russian module in Gateway would have required Russian crew members on the station. But Russia has neither a spacecraft nor a rocket to reach it, so cosmonauts would have had to travel there and back exclusively on the American Orion/SLS system. Moreover, Russia insisted not only on building the airlock to Russian standards but also on enabling docking of its future PTK-L spacecraft—the very one whose development has now ceased, and the rocket capable of delivering it to the Moon won’t appear for at least the next 15 years. When Roscosmos announced its withdrawal in September 2018, director Dmitry Rogozin promised an independent uncrewed lunar program starting in 2021 (in fact, Luna‑25 did not launch until 2023 and failed). He also claimed that, as a major space power, Russia could build its own cislunar station together with friendly BRICS countries. None of that came to pass. The net result: Russia has shown itself as an inconvenient, unreliable, and willful partner that constantly claims high positions without the means to back it up.

Fifth, the economic factor is worth noting. At first glance, it seems to favor closer U.S.–Russian cooperation in space, much like at the start of the ISS era: both Roscosmos and NASA face shrinking space budgets. For NASA, cuts come from the Trump administration; for Russia, from the war in Ukraine. But the ISS analogy does not hold. As already noted, Russia has nothing to offer the United States for lunar exploration, while the American Artemis program has already reached the stage of test flights to the Moon. NASA — especially given SpaceX’s capabilities — has enough capacity to proceed without involving Russia. Moreover, cuts to NASA’s budget are not driven by economic necessity but by the president’s personal decisions — decisions he has repeatedly reversed — and are by definition temporary because of the limited length of any presidential term. Therefore, a short-term dip in NASA funding cannot justify the long-term downsides of bringing Russia into the program.

I should note that inviting Russia into an American lunar program (given Russia’s effective lack of its own) would look incoherent in light of Russia’s 2024 intergovernmental agreement with China — and a roster of partner states (Belarus, Pakistan, Azerbaijan, Venezuela, South Africa, Egypt, Thailand, Serbia, Nicaragua, Senegal, Djibouti, Ethiopia, and Bolivia) — to build a lunar station, and given the fact that Moscow has opted out of both Gateway and Artemis.

Taken together, U.S. cooperation with Russia on lunar research and development contradicts America’s national interests and is unlikely in practice. Moreover, from the standpoint of U.S. interests in space, Russia should be set aside, and a proposal for joint lunar exploration should be made to China, which — unlike Russia — has a long-term, steadily implemented space program, including concrete plans for the Moon.

Today the U.S. operates its ISS segment in low Earth orbit while China has assembled a new multi‑module orbital complex that, without foreign crews, permits military‑relevant experiments in orbit. China has not only returned lunar samples but also achieved the historic first landing on the Moon’s far side and, more recently, returned samples from that far side. Now and in the coming years, China — not Russia — is America’s primary space competitor.

The arguments for U.S. engagement with China are straightforward. Complex space programs bind partners together over the long term, as the ISS shows. Even quarreling on Earth, the US and Russia were compelled to continue ISS cooperation because the Russian and American segments are deeply integrated.

Complex, science-intensive, and expensive joint projects bind partners so tightly that even emerging earthly disputes are partially mitigated by such endeavors. Therefore, for the US, confrontation with China could be substantially reduced through the creation of a joint lunar base. Moreover, establishing a lunar base would divert significant Chinese resources — under American oversight — thus reducing the remaining resources available to China for space projects detrimental to US interests.

As for Russia as a potential partner in lunar projects, it is no longer attractive to either the U.S. or China: it cannot contribute enabling technologies or unique expertise and cannot significantly lower program costs, serving not as a donor but merely as a dragging burden. The cautionary example is the “Phobos-Grunt” program to return samples from Mars’s moon, with a Chinese transit spacecraft installed on the Russian interplanetary station. After 15 years of development and three design teams replaced, Phobos-Grunt was launched on November 9, 2011, but failed to escape low Earth orbit, going silent immediately after launch. On January 15, 2012, Phobos-Grunt along with the Chinese spacecraft burned up in Earth’s atmosphere. China, drawing the right conclusions from the failed collaboration with Russia, proceeded to Mars independently and on May 14, 2021, delivered its rover to the Martian surface. Meanwhile, Russia has no real plans for launches toward Mars anymore.

Russian space efforts over recent decades show a downward trend, visible in the retreat from a full lunar program and in plans to build the high‑inclination Russian Orbital Service Station (ROSS) by 2030 — a move that would preserve older technology for years to come. In space, Russia has fallen behind the leaders forever.