Each year, the organization Scholars at Risk (SAR) releases the Free to Think report, which acts as a global barometer for academic freedom. The latest edition, published on October 1, 2025, highlights a troubling trend: since 2018, declines in academic freedom metrics have emerged not just in autocracies but also in long-established democracies. The report, covering July 2024 to June 2025, documents 395 attacks worldwide. Although the total numbers show only a modest increase from the previous year, incidents threatening the physical safety of students and faculty have nearly doubled.

Top news on scientists’ work and experiences during the war, along with videos and infographics — subscribe to the T-invariant Telegram channel to stay updated.

The data for the Free to Think report are collected through the Academic Freedom Monitoring Project (AFMP), an initiative run by SAR that relies on open sources and firsthand witness accounts. AFMP tracks incidents and sorts them into several categories:

- violations of physical security (killings, violence, disappearances);

- unjustified legal proceedings and imprisonment (prosecution, imprisonment);

- unjustified dismissals and expulsions (loss of position);

- restrictions on academic mobility (travel restrictions) and others.

Compared with last year’s report, there was a sharp increase — from 98 to 183 cases in incidents tied to threats against the physical safety of students and faculty. The number of arbitrary arrests has also risen, from 57 to 83.

T-invariant Backgrounder

Scholars at Risk is an international network founded in 1999, dedicated to safeguarding scholars facing persecution and monitoring violations of academic freedom. The Free to Think project, launched in 2015, aims to spotlight these issues for governments, academic communities, and the broader public.

Another key source of data for the 2025 Free to Think report is the Academic Freedom Index (AFi), developed by an independent consortium that includes Friedrich-Alexander University (FAU) in Erlangen-Nuremberg and the V-Dem Institute. It relies on input from over two thousand scholars worldwide, yielding comparable time-series data across countries and territories — ideal for spotting global patterns.

The AFi is a composite index scored from 0 to 1. It aggregates five core dimensions:

- freedom of research and teaching;

- freedom of academic exchange and knowledge dissemination;

- institutional autonomy of universities;

- campus inviolability;

- freedom of academic and cultural expression.

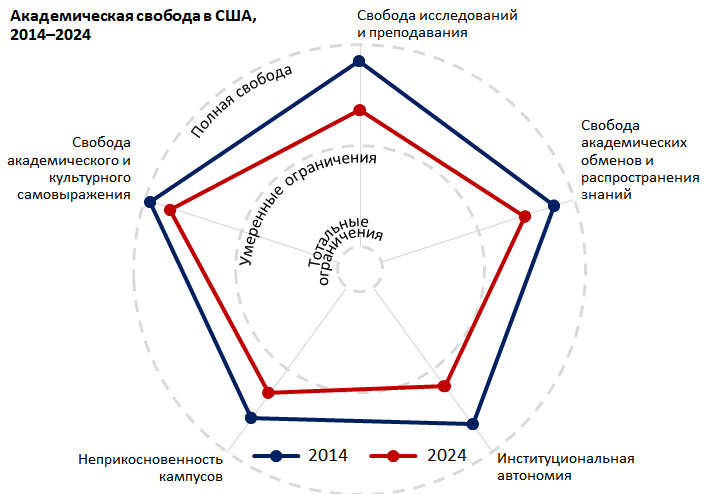

Experts rate each component on a 0–4 scale, which is then combined into the AFi via a custom Bayesian model. This approach adjusts for differences in expert judgment and the challenges of assessing each dimension in different contexts. Figure 1 shows the erosion of academic freedom in the United States over the past decade, broken down by component.

Fig. 1. According to V-Dem data, academic freedom in the US has declined across all five indicators over the past decade. From 2014–2019, the AFi hovered around 0.91–0.92, placing the country in the “fully free” category; by 2024, it fell to 0.68, classified as “mostly free”. Based on a figure from Academic Freedom Index: 2025 Update.

Cracks in the Foundation of Academic Freedom

One of the report’s most alarming conclusions is the surge in attacks on academic freedom in countries with apparently robust democratic institutions: “Since 2018, however, a growing number of the incidents included in the AFMP have taken place in countries with ostensibly strong democratic institutions.” The authors’ use of “ostensibly” underscores a key point — even in nations regarded as mature democracies, academic freedom is eroding under authoritarian pressures: “elected officials with autocratic impulses are using both the levers of democracy and extralegal administrative measures.”

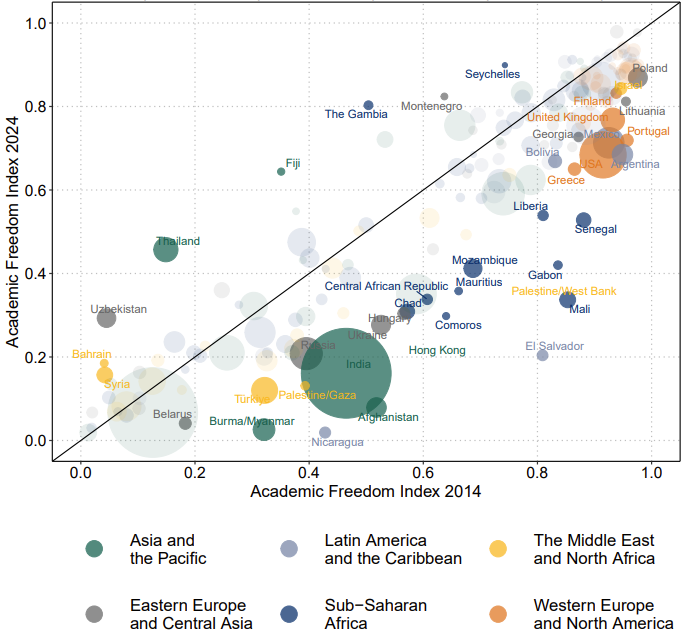

The AFi update report from March 2025 corroborates this. From 2014 to 2024, only eight countries worldwide saw statistically significant improvements in academic freedom, with only one in Europe — Montenegro. By contrast, 36 countries experienced significant declines, affecting not only autocracies such as Russia, Turkey, and Belarus but also democracies including the UK, US, Finland, Poland, Lithuania, Portugal, Greece, Argentina, and Georgia.

Fig. 2. Changes in AFi from 2014 to 2024. Circle sizes reflect population. Countries with AFi gains lie above the diagonal; declines, below. Faint circles near the line indicate changes lacking statistical significance. Source: Academic Freedom Index: 2025 Update.

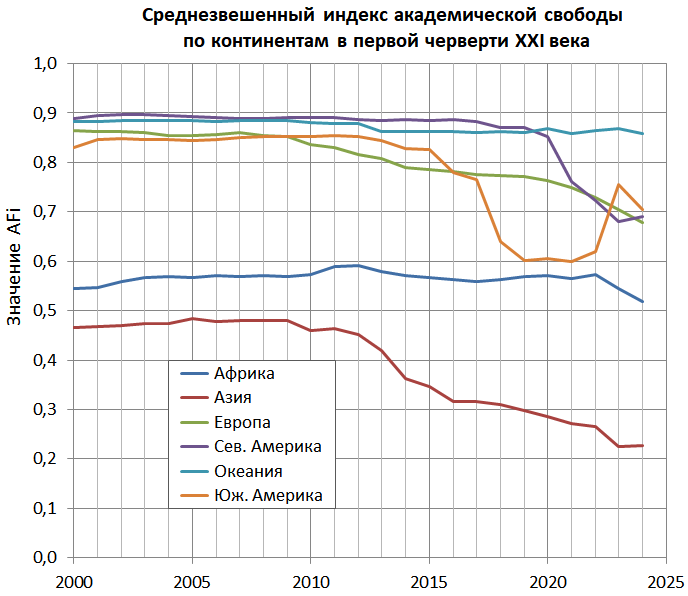

Digging into the AFi’s long-term trends reveals that erosion of academic freedom predated SAR’s observations. In the early 2000s, regional averages weighted by population remained stable — high (0.85–0.90) in Europe, the Americas, and Oceania; moderate (0.47–0.57) in Asia and Africa. But starting around 2010, scores started to decline in Asia and Europe, then in South America, and from 2018 onward, in North America as well. Oceania has remained largely unaffected, while Africa has been affected to a lesser degree.

Fig. 3. Country indices were averaged using population-based weights. This and subsequent charts draw on historical AFi data from Our World in Data.

Out of Sight, Out of Accountability

Unlike the AFi, Free to Think is not a representative snapshot of global academic freedom. Instead, it’s a curated collection of cases, selected to highlight the breadth of challenges and draw attention to human rights abuses in academic settings. SAR’s data-gathering capacity varies by country, especially since only incidents are included only when verified by at least two independent sources.

The report cautions that fewer reported incidents from severely repressive regimes does not necessarily indicate progress: “a lower number of reported incidents between years may in fact result from more successful repression of academic freedom.” Thus, countries like Myanmar, Nicaragua, or the Palestinian territories (noted in the report as Occupied Palestinian Territories and Gaza Strip — T-invariant edit) that saw high violation counts previously but lower now “may warrant greater attention, not less, precisely because the decrease may be indicative of the highest levels of repression.”

With that in mind, it’s unsurprising that the United States tops the list with 62 incidents. Even in 2024, cases on US campuses jumped from the usual 15–20 a year to over 80 — and the pace has not slowed: 43 were recorded in the first half of the year alone. This erosion is rippling internationally, with fewer foreign students and scholars opting for the US, while European and Asian universities roll out initiatives to lure American talent. Cuts to US research funding have disrupted collaborations worldwide, a phenomenon SAR calls “an unprecedented, voluntary dismantling of the US as a global education,research, and innovation superpower.”

Bangladesh ranks second with 57 incidents, where nationwide student protests erupted in July 2024, shaking the country’s entire higher education system. The government responded with brutal, systematic force, injuring thousands and killing roughly 1,400 people from July 15 to August 5, 2024. India ranks third with 45, as the central government has tightened its grip on higher education, eroding university autonomy. For example, institutions like the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, University of Mumbai, Jamia Millia Islamia, Osmania University, and Panjab University now require prior approval for student meetings, demonstrations, or the distribution of slogans.

Up-to-date videos on science during wartime, interviews, podcasts, and streams with prominent scientists — subscribe to the T-invariant YouTube channel!

Given the limited availability of information, we should not be misled by the low counts for Belarus (2) and Russia (6) — even fewer than those listed in T-invariant’s Chronicles of the Persecution of Scientists, and below Ukraine’s 14 — a discrepancy that likely reflect greater transparency and data availability from the latter.

Three Patterns of Decline

Each Free to Think report spotlights a handful of countries for in-depth coverage, apparently to illuminate key trends. This year, it focuses on 16 nations, with brief updates for seven more from last year’s edition. A closer look reveals three recurring patterns in the erosion of academic freedom.

1. Academic freedom often crumbles amid severe political upheavals. Take Turkey, for example: after the failed 2016 coup attempt, universities underwent a massive purge, with around 4,000 professors dismissed — and the AFi dropped from 0.3 to 0.07, only now showing tentative recovery. In Belarus, where academic freedom was already low (0.19), post-2020 protest crackdowns dropped it to 0.07, then to 0.04. The US’s abrupt 2021 exit from Afghanistan tanked the country’s AFi from 0.5 to under 0.1. Myanmar’s 2021 military coup obliterated freedoms there, from 0.4 to 0.02. Ukraine is a distinct case: its AFi was 0.62 in 2021 but has been declining at an accelerating pace amid wartime conditions, hitting 0.24 by 2024. This decline reflects the broader war damage — during war, it becomes increasingly difficult to preserve internal freedoms.

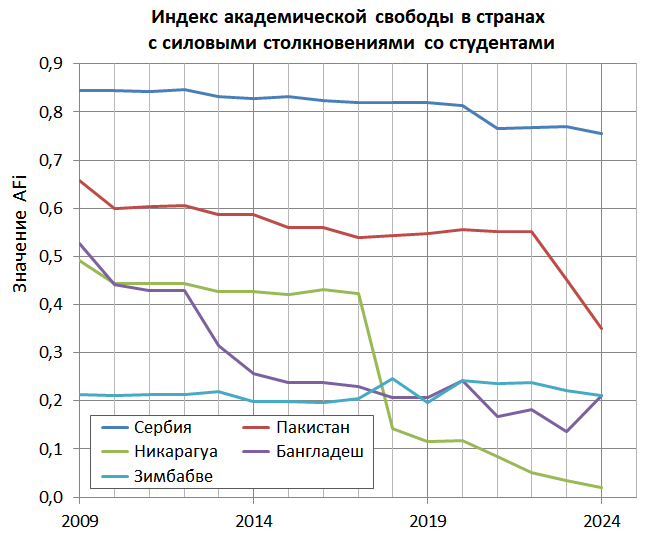

2. Another pattern emerges in Bangladesh, Pakistan, Serbia, Zimbabwe, and Nicaragua, where large-scale student protests were met with state violence. In the first four, academic freedom losses stayed contained; in Nicaragua, it was virtually eradicated in 2018 after police stormed university campuses — hotbeds of opposition. Over 150 professors were fired, some universities shuttered, and a 2020 “foreign agents” law (mirroring Russia’s controversial legislation labeling NGOs and individuals receiving foreign funding as foreign agents) cemented the regime’s control. The AFi fell from 0.42 to 0.14, now at 0.02. Nicaragua’s academic community suffered total institutional defeat in the clash with authoritarian power, unlike the partial pushback seen in the other four countries — though the downward trend in Bangladesh and Pakistan remain concerning.

Fig. 4. Nicaragua’s academic freedom was crushed in a showdown with authoritarian forces.

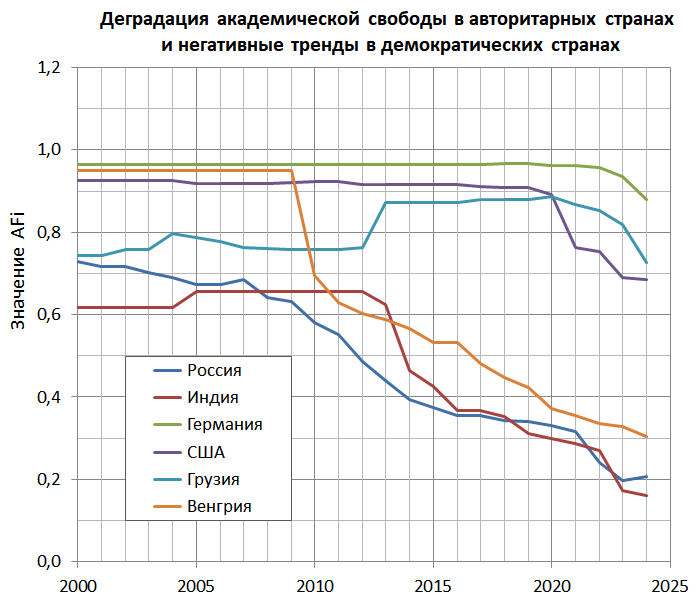

3. A third pattern involves gradual erosion under leaders with autocratic impulses backed by popular support. Russia’s trajectory exemplifies this, unfolding steadily under Putin’s rule and tightening authoritarian control (accelerating post-2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine, veering toward the first pattern). India has mirrored this trend since the 2014 rise of the Hindu nationalist party. Hungary’s AFi plummeted in 2010 with Viktor Orbán’s victory, and the decline has persisted. Georgia’s index has worsened since 2020 amid increasing Russian influence. Yet SAR notes similar trends in Western democracies such as the United States (from 2020) and Germany (from 2023).

Fig. 5. Academic freedom’s erosion under authoritarian influence.

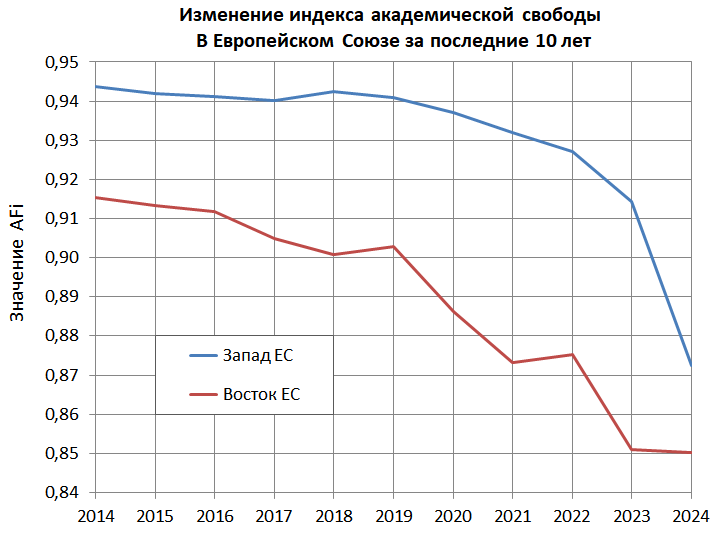

Declines in democracies have not yet turned catastrophic, yet it is already clear that this is not a random fluctuation but an emerging trend. Drawing on AFi data, we traced this trend across the European Union. In 2014, post-communist states lagged behind Western Europe and began to decline earlier. But from 2020 — coinciding with the COVID-19 pandemic — Western EU countries have joined the downward trend, surpassing declines in Eastern Europe over the past year. Somewhat unexpectedly, Eastern Europe now leads the world in academic freedom: Czechia ranks first and Estonia second.

Fig. 6. Academic freedom’s downturn in the European Union. Country weights were population-proportional.

Universities Belong to Future Generations

Academic freedom is not merely a right but a special condition that allows scholars and students to conduct research, exchange ideas, and challenge entrenched knowledge without fear of external interference. Unlike core human rights such as the right to life, enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, it is a distinct framework for the university realm, where fresh insights into the world take shape.

The concept of academic freedom itself evolves over time. For example, until 2011, the AFi was originally calculated from four dimensions — research freedom, academic exchange, institutional autonomy, and campus inviolability — but later added a fifth: freedom of expression.

Academic freedom provides a rare space where individuals can express ideas that challenge convention without fear. Without it, bold rethinking of society’s direction stalls; universities become loyalty tests rather than forums for rigorous debate, where the merit of arguments yields to allegiance to outside agendas — political, religious, or economic.

For a vivid example, consider an anecdote shared by Eduard Galazhinsky, rector of Tomsk State University (a leading Russian institution). In the mid-2010s, during student unrest at an Amsterdam university, protesters stormed the rector’s office holding signs. The rector came out, indignant: “What’s all this noise? Get out of my university!” This sparked a debate that continues today: Who truly owns the university — students, their tuition-paying parents, the faculty, academy, or the state? They concluded that it belongs to future generations. “A university is a space where young people unlock their potential and assume responsibility for the future of their nation — and of humanity. It’s the engine of elite renewal and human capital, those who will shape our shared future.”

At its core, the question of academic freedom is a choice of how the next generation of intellectuals will be shaped—those who will define society’s future trajectory. One path is the top-down imposition of values, typical for closed, archaic societies that change slowly; the other is the nurturing of independent reflection through the competition of ideas. The latter — sustained by academic freedom — lets emerging leaders venture even into fringe ideas, thereby fostering the intellectual agility societies need to adapt and progress.

Update October 11, 2025. Clarified how the report identifies Palestinian territories.