In several European countries simultaneously, Russian students have been banned from studying IT-related specialties. Cases have also emerged of restrictions on admission (for example, to the politically sensitive program “Arctic Shipping”). Previously, export-control procedures applied only to university and research-center employees, visiting researchers, and collaboration participants; now the same checks are being applied to students. For instance, the University of Bonn has blocked 65 students from Russia from accessing IT courses. Similar measures have been taken against students from China and Iran. Human-rights advocates call this outright discrimination on the basis of nationality: education has never fallen under EU sanctions. T-invariant spoke with students affected by the restrictions and examined how export control works in German universities in both theory and practice.

Top news on scientists’ work and experiences during the war, along with videos and infographics — subscribe to the T-invariant Telegram channel to stay updated.

On November 19, 2025, it became known that the University Centre in Svalbard (Norway) prohibited a Russian student from studying Arctic shipping. This was reported by Gera Ugryumova, founder of the human-rights project Iskra (which fights discrimination against Russians who left the country after the war began).

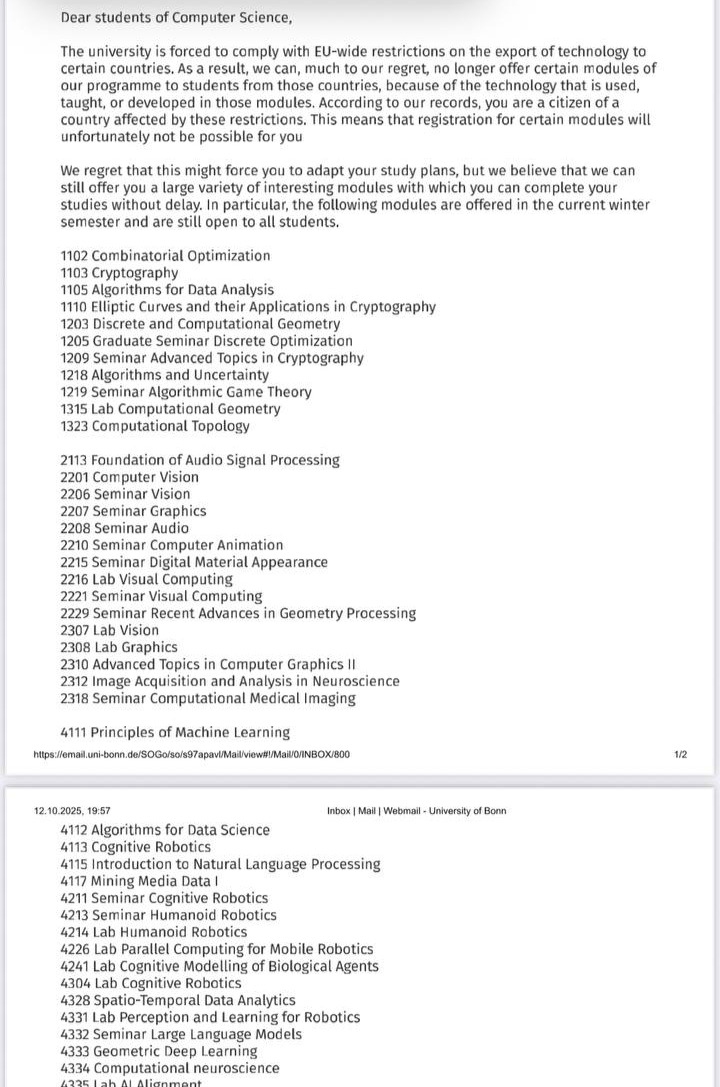

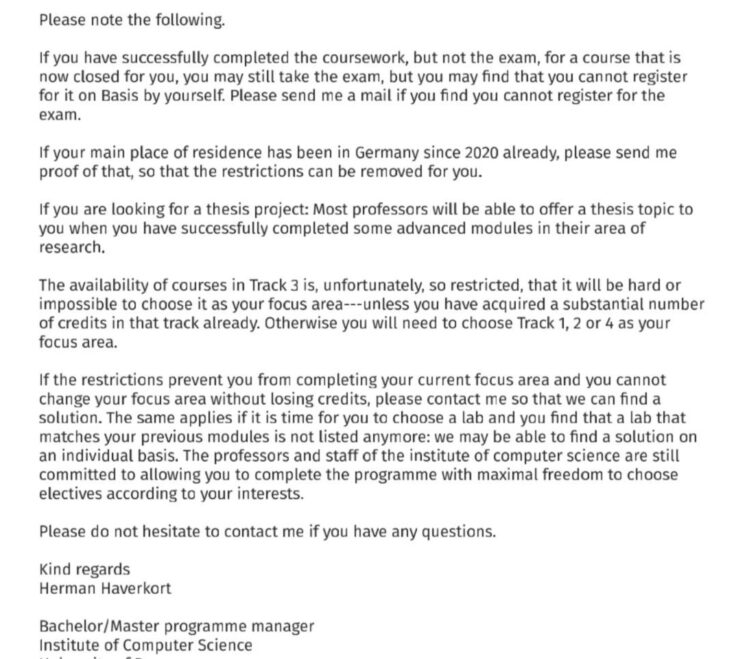

A far bigger and more striking case occurred in Germany in October 2025. Master’s students at the University of Bonn holding Russian, Iranian, or Chinese passports received letters stating that, due to sanctions, they were being denied access to most courses in cybersecurity, cryptography, and IT security. The entire Communication Management track has been placed under a total ban — students are offered either an urgent change of major or transfer to another university. The university says it is complying with a federal government requirement to control dual-use technologies.

Professor Andreas Archut, Head of Communications at the University of Bonn, told T-invariant that a review revealed that students from sanctioned countries cannot be enrolled in certain modules on the master’s programs in cybersecurity and computer science. “This currently affects 65 Russian passport holders. At the same time, they retain the opportunity to choose alternative modules and continue their studies at the university. The university openly opposes any form of discrimination and considers attracting international students one of its top priorities,” Andreas Archut stated.

“The passage about discrimination is pure demagoguery. There are many examples of discrimination based on passport color — from European banking and fintech to science and education. As for the restrictions on students at the University of Bonn, it’s still unclear whether this is already a systemic policy or merely an overzealous implementation at one particular university. Federal and European authorities issue broadly worded documents and various recommendations. Then different agencies in different German states interpret these prohibitions in different ways. Research centers tend to follow the rules more strictly, while universities have traditionally been more liberal,” a German researcher explained to T-invariant on condition of anonymity.

What the students say

“The Computer Science program I’m enrolled in is divided into four tracks: Algorithmics (theoretical algorithms); Graphics, Vision and Audio; Communication Management (IT and security); and Intelligent Systems (AI),” says Semyon, a University of Bonn student from Russia (name changed at the interviewee’s request). “We were informed that a number of courses are now unavailable to students from Russia, Iran, and China. The worst hit are those who chose Communication Management: the entire track is banned. They now have to either transfer to another university or switch majors. They say that over time some courses will be reworked, so ‘sanctioned’ students will be able to attend almost everything except a few lectures, and it shouldn’t prevent them from passing exams. They may make exceptions for those who can prove they do not plan to return to Russia — for example, political activists or people in registered same-sex partnerships.”

“With the exception of cybersecurity, the restrictions are generally not critical,” clarifies Alexey, another University of Bonn student (name also changed at his request). They mainly affect lab courses, where you carry out a programming project under a professor’s supervision. We received a list of restricted labs, but the same email added: if this causes problems (you can’t earn enough credits, can’t write your thesis in another block, etc.), write to us — we’ll sort it out individually. Such emails have come more than once. I know several cases where a student simply talked to the professor and the issue was resolved. These aren’t isolated stories.”

The letter states that if a student can prove they have lived in Germany for the last five years, the restrictions may be lifted. From the letter it might seem that the university is only simulating tough measures while in practice students can resolve everything individually.

“No, that’s not the case,” Alexey objects. “For those who came specifically for cybersecurity and cryptography, the changes are a serious obstacle. Plus, we’ve all been left in limbo: the promises are only verbal, while the official rules say something completely different.”

Naturally, the immediate question is: did the university decide this on its own, or was it ordered from above? Is Bonn the only university in Germany to introduce bans based solely on passport, or did it simply get caught first?

“We had a meeting with the student council (important: these are not official administration representatives),” Alexey recounts. “They explained that a law restricting the export of technology had already been passed in 2021. The university falls under the rules for dual-use items. According to the council, the university received a letter from federal authorities saying, in effect, ‘You are poorly complying with the law; third-country nationals must not study technologies that can be used for military purposes.’”

Up-to-date videos on science during wartime, interviews, podcasts, and streams with prominent scientists — subscribe to the T-invariant YouTube channel!

“If you believe the official version, the decision came from above,” says Semyon. “We were told that Bonn was simply the first university that was singled out for non-compliance with sanctions. At what level — Germany or the EU — is unclear. The university supposedly doesn’t fully understand what is required of it, so it is over-complying to the maximum extent and will later soften the measures to make life easier for students. Not everyone believes this: it looks suspicious that, out of all German universities, only Bonn turned out to be the sole ‘violator.’”

How Export Control Operates in German Universities

The websites of many German universities contain detailed information on export control — and it is clear that each university explains the rules to its staff in its own way. However, T-invariant could not find such a page on the University of Bonn website: there are only contact details for the responsible officers.

For example, the University of Konstanz describes the restrictions as follows:

“Export control is intended to prevent the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and to restrict the uncontrolled export of armaments. Sensitive goods, technologies, and knowledge must not be exported for the purposes of repression, human-rights violations, or terrorism. These measures are part of an internationally coordinated strategy supported by most industrialized countries… The goal is not to restrict academic freedom but to prevent the misuse of sensitive goods, technologies, information, and software. Potentially critical cases must be identified early and handled in accordance with legal requirements. Depending on the situation, certain activities may require a permit or even be prohibited.”

The page provides multiple links to the legal basis and compiles all kinds of recommendations and clarifications. There is also an interactive map of countries under export-control requirements published by the Federal Office for Economic Affairs and Export Control (BAFA) — it marks not only Russia, China, and Iran but also, for example, Ukraine, Moldova, and Bosnia & Herzegovina.

The restrictions listed in the letter sent to Bonn students match almost word-for-word the export-control rules described in great detail on the website of Ulm University. For instance, the rules provide for less restrictive treatment of individuals who have lived in the EU for the past five years:

“If the person has not resided exclusively in an EU member state during the last five years, please submit that person’s CV along with the application to the export-control office before signing an admission agreement or initiating an employment contract procedure with Dezernat III Personal.”

Among the separately highlighted “red flags” for export control are items related to ‘particularly powerful computers or cryptanalytic processes’. These are precisely the areas that have come under the strictest prohibition for the sanctioned students in Bonn.

In none of the universities that have dedicated “export control” sections on their websites (for example, the University of Stuttgart) is it mentioned that these rules extend to students.

“The first risk indicator in export control is the color of the passport. If it’s Russia, China, Iran — they dig deeper. If the CV shows ties to a sanctioned organization, that’s the final red flag. It doesn’t matter whether you worked or even just studied at, say, MIPT (Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology) — you’re done,” a German researcher familiar with the procedures explained to T-invariant.

“What is prohibited is not access to the materials themselves, but formal instruction and the issuance of certifying documents”

Gera Ugryumova considers the University of Bonn’s actions unlawful: “The university refers to sanctions and calls its courses ‘technical assistance to Russia’ (primarily in dual-use technologies — T-invariant), although this has been examined many times already: education is not subject to sanctions. We sent a petition to the European Parliament and received an official response: there are no restrictions for students from Russia.”

At the same time, Ugryumova is confident that it is worth fighting. Iskra already has a successful appeal at the Vienna University of Technology. “We proved that sanctions cannot prevent a woman from studying. Unfortunately, by the time the review was completed, the application deadline had passed. But now future applicants can refer to this precedent,” Ugryumova says.

According to her, the situation is even worse in some places: in the Czech Republic the restrictions have been introduced by the state, while in Switzerland it is left to individual universities — “they do whatever they want.”

Dmitry Dubrovsky, a Russian historian and sociologist, PhD, and lecturer at Charles University, largely agrees with her: “Yes, there are EU guidelines on preventing the proliferation of dual-use technologies. The logic is clear: to deny the aggressor country access to military technologies. But we are talking about open educational programs. In theory, a graduate could go work for a company with classified projects — but that is a question for the employer and its security-clearance procedures, not the university.”

In Dubrovsky’s view, the Bonn case is largely explained by Germany’s federal structure: “Most likely this is an initiative of a specific state (Land). Approaches to security and migrants vary widely across German Länder. In Switzerland similar problems occurred only in Zürich — I suspect it’s a one-off related to a particular canton. In the Czech Republic universities openly publish lists of programs closed to Russians and Belarusians.”

A quick search shows such announcements on the websites of the Czech Technical University in Prague, Brno University of Technology, Charles University, and others.

“We are dealing with a very elastic interpretation of ‘technology proliferation’ and classic over-compliance,” Dubrovsky sums up. “Banning students from certain countries from taking specific courses or programs is, frankly, a foolish idea. First, most of these students have already left the country and have no intention of returning. Second — and most importantly — teaching does not necessarily involve classified technology. Much of the material is publicly available anyway, yet some universities for some reason consider the very act of teaching to be a transfer of information prohibited by EU sanctions.”

Alexey confirms Dubrovsky’s words: “Essentially, it’s restrictions based on passport color. Russian, Chinese, and especially Iranian — boom, you’re in the risk zone. The desire to make the country safer is understandable; drones are reaching here now too. But on the other hand — it’s pointless. No one checks passports at lectures; you just show up and sit there. The real issue is only with registering for exams and getting credits.”

The materials, by the way, turned out to be accessible: Alexey and I tested it — he had no trouble opening everything he’s supposedly “prohibited” to see.

“The logic is simple,” Dubrovsky explains the paradox. “What is prohibited is not access to the materials themselves, but formal instruction and the issuance of certifying documents. You can watch the lectures, but you can’t earn credits or have them recorded in your diploma.”