Berlin-based nonprofit organization Science at Risk Emergency Office (hereinafter SAR, a project of the German NGO Akademisches Netzwerk Osteuropa) has released its latest monitoring reports on the state of academic freedom in Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine. These reports are based on incident monitoring, interviews with scholars, and analysis of open sources. T-invariant compares these reports with one another and with the global Free to Think (FTT) 2025 report on academic freedom, an analytical overview of which we published last year. The new SAR documents provide a more detailed account of the processes unfolding in the three countries affected by war and authoritarianism, allowing us to trace the mechanisms of academic freedom’s degradation.

Top news on scientists’ work and experiences during the war, along with videos and infographics — subscribe to the T-invariant Telegram channel to stay updated.

Amid the global rise of authoritarian tendencies, political crises, and external threats, academic freedom is facing systematic pressure, leading to a decline in societies’ intellectual potential and a weakening of their resilience. In October 2025, the international Scholars at Risk network (not to be confused with Science at Risk) released its global Free to Think monitoring report (FTT), which compared incident data from 49 countries with trends in the Academic Freedom Index (AFi). The report noted a decline in academic freedom across most regions of the world (significant drops in 36 countries between 2014 and 2024, including democracies). Last year T-invariant published an analytical overview of the FTT-2025 report, identifying three patterns of academic freedom degradation.

Compared with FTT, the Science at Risk (SAR) reports provide detailed accounts of the mechanisms of academic freedom degradation in individual countries — Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine — analyzing each component of the composite AFi index. For each country, the researchers propose a periodization of the post-Soviet era, demonstrating how changes in individual AFi components relate to specific events — elections, protests, military actions.

The Academic Freedom Index (AFi) was developed by an international collaboration (V-Dem Institute, Global Public Policy Institute, and others). AFi ranges from 0 to 1 and is composed of the following five components (each scored 0–4), determined by expert assessments from more than 2,000 scholars:

- FRT — freedom to research and teach;

- IA — institutional autonomy;

- CI — campus integrity;

- AED — freedom of academic exchange and dissemination;

- ACE — freedom of academic and cultural expressions.

SAR reports have been published annually since 2023. In this analytical overview of the 2025 reports, T-invariant demonstrates how the processes in the three post-Soviet countries reproduce the previously identified patterns of academic freedom degradation. We also refine some of the reports’ data in light of the end of 2025 and put forward new analytical hypotheses, the most important of which concerns the “contagiousness” of unfreedom, which can spread — including to democratic states — as societies respond to existential threats.

Patterns of Academic Freedom Degradation

According to the latest FTT report, academic freedom levels are declining in most countries this decade. This trend results from political instability, military threats, and the strengthening of authoritarian regimes. In our previous overview, we identified three main patterns of academic freedom degradation: gradual erosion under authoritarian pressure (Russia, Hungary, India), sharp collapse due to political or military crisis (Afghanistan, Myanmar, Belarus), and institutional defeat of the academic community in direct confrontation with authoritarian power (Nicaragua, Bangladesh). The new Science at Risk reports on Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine enable a deeper examination of these patterns, showing how they manifest in AFi component dynamics and lead to a decline in countries’ positions in the global academic freedom ranking.

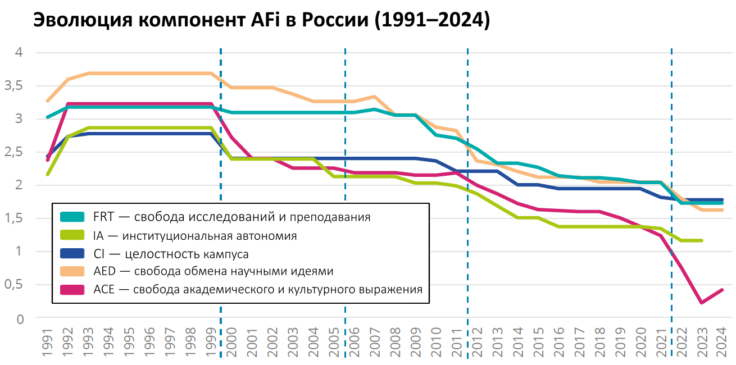

Russia is a vivid example of gradual erosion of academic freedom over a quarter of a century. In the 1990s, academic freedom in Russia stood at a relatively high level by global standards. The decline coincided with the Second Chechen War and Vladimir Putin’s rise to power. Freedom of expression (ACE) suffered the most at that time, alongside declines in university autonomy (IA) and campus integrity (CI), apparently linked to heightened security measures amid the regional war. A long-term downward trend also emerged in freedom of academic exchange and knowledge dissemination (AED). Only freedom to research and teach (FRT) remained largely unaffected, enabling the emergence and strengthening of such prominent institutions as HSE, the European University in St. Petersburg, and Shaninka.

The next noticeable drop occurred at the start of Putin’s third presidential term, following protests over election fraud. From 2012 onward, the trend toward replacing elected rectors with appointees intensified, the Russian Academy of Sciences reform was launched (ultimately stripping it of independence and control over its institutes), and laws on “foreign agents” and “undesirable organizations” were adopted. Importantly, the decline in freedom of expression (ACE) and freedom to research and teach (FRT) began two years earlier — still under the “liberal” President Medvedev, who launched the image-focused Skolkovo science and education project amid a popular science boom in Russia.

The third stage of academic freedom degradation accompanied the invasion of Ukraine and primarily affected freedom of expression (ACE), which the SAR report describes as “de facto military censorship.” However, military censors who pre-approved publications were not involved. A more accurate phrasing from the SAR report is thus “a fully integrated system of political control.”

Over the 25 years since Putin came to power (2000–2024), Russia’s AFi index fell from 0.73 to 0.21, placing the country in the bottom 20% of the global academic freedom ranking — on par with Venezuela, which, incidentally, followed an almost identical trajectory during this period.

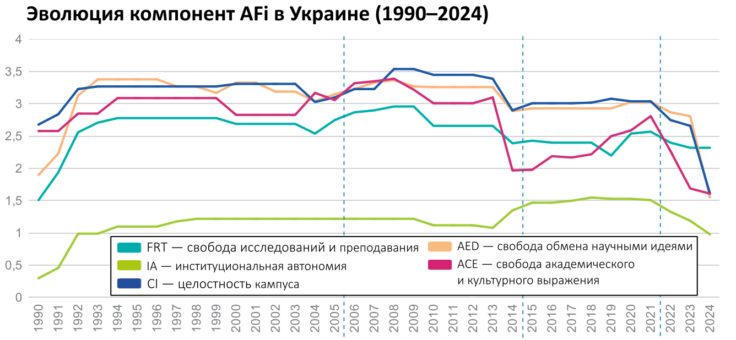

Ukraine and Belarus show a different pattern — a sharp drop in academic freedom resulting from social cataclysms. Yet there is a fundamental difference between them: the Belarusian crisis was entirely endogenous, while the Ukrainian one was exogenous, triggered by Russian aggression.

Ukraine experienced two sharp declines in academic freedom: after the annexation of Crimea in 2014 and with the onset of full-scale Russia’s invasion in 2022. In both cases, freedom of expression (ACE) suffered the most. This is linked to society’s consolidation around national identity and the severance of all ties — including intellectual ones — with the aggressor state (the “rally ’round the flag” effect) during external aggression. The fact that campus integrity (CI) and academic exchange freedom (AED) declined less and later than freedom of expression (ACE), while freedom to research and teach (FRT) was almost unaffected, suggests that in Ukraine the authorities largely followed public sentiment rather than imposing restrictions. Nevertheless, self-censorship — however understandable its causes — reduces freedom of speech and thought just as effectively as direct censorship. This is one of the direct consequences of war.

After the annexation of Crimea, the AFi index continued to grow slowly for some time, but with the full-scale war it plummeted over three years — from 0.62 to 0.28, its lowest level since 1990. Globally, this pushed Ukraine to a position comparable to Ethiopia. Given the scale of destruction and human losses, the report notes that without international support for recovery, “there is a substantial risk of lasting erosion of Ukraine’s intellectual capacity”.

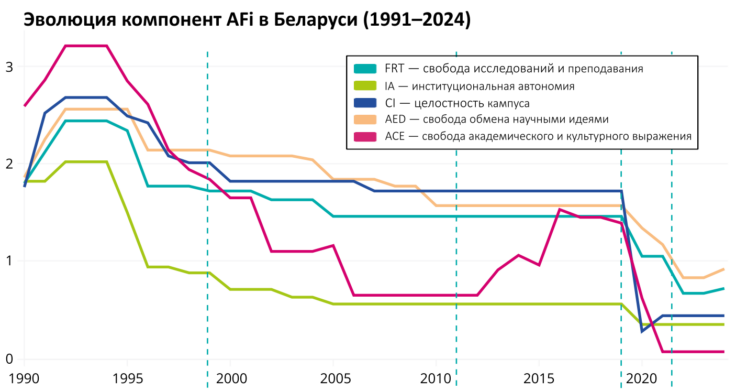

In Belarus, the upheaval that destroyed academic freedom was caused by internal factors — the brutal suppression of mass protests following the falsified 2020 presidential election. As the SAR report notes, universities that still allowed some freedom of thought were perceived by the authorities as potential centers of political mobilization. The state’s response was systematic and became an institutional turning point for Belarusian higher education. The report emphasizes that pressure on the academic community went beyond targeted repression and aimed to dismantle universities as autonomous institutions, affecting all levels — from students to rectors.

After the 2020 protests were crushed, academic freedom in Belarus ceased to be merely “limited” and became structurally incompatible with the existing political system. This situation shows that the degradation of academic freedom in Belarus partially corresponds to the second pattern — the academic community’s defeat in confrontation with authoritarian power.

Belarus’s overall AFi index collapsed from 0.19 in 2019 to 0.04 in 2024, placing the country close to the bottom of the global ranking, between Afghanistan and Nicaragua. “Academic freedom in Belarus is not merely threatened — it has been systematically dismantled,” the SAR report states.

It is worth noting that the current crisis of academic freedom in Belarus is not the first. The initial one occurred in 1994–1996, immediately after Alexander Lukashenko came to power as the presidency. Within two years he sharply increased state control over universities and introduced strict censorship directed against both Belarusian nationalists and any Western influence. The period of relatively free post-Soviet education in the country lasted only 4–5 years.

Common Vulnerability Factors: Comparative Analysis Across Countries

Despite the different patterns of academic freedom destruction in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus, several common features emerge.

Politicization of universities and ideological control. In all three countries, universities face ideological pressure — albeit of different kinds — leading to declines in AFi components such as freedom to research and teach (FRT) and freedom of academic and cultural expression (ACE).

In Russia politicization manifests as militarization. In 2022, shortly after the invasion, 184 rectors of leading universities signed a statement supporting the “special military operation.” Most of them are state-appointed administrators rather than representatives of the academic community, yet they shape state policy within universities, which often become centers of pro-war propaganda. In December 2022 the Ministry of Science and Higher Education recommended including a “Basics of Military Training” course in curricula; the number of university military training centers grew from 104 to 120 during the war. Mandatory ideological courses “Fundamentals of Russian Statehood” and “History of Russia” containing anti-Ukrainian rhetoric were also introduced.

In Belarus a key marker has been mandatory courses on “ideology of the Belarusian state.” The education system is increasingly integrated with Russia’s one, including through shared textbooks and programs, while military-patriotic propaganda permeates the entire educational pipeline — from kindergarten to university.

In Ukraine self-censorship grew after the annexation of Crimea on issues related to the war, collaborationism, and national identity. In 2025 this trend was formalized by a law “On the Basic Principles of State Policy on the National Memory of the Ukrainian People.” The establishment of a single mandatory interpretation of certain historical events across politics, education, and public space narrows the field of academic discussion. A striking example is the case of historian Marta Havryshko. After criticizing ethno-nationalist policies she and her family received threats, which undermined trust within the academic community and led to her departure from the country.

Weakening of institutional autonomy (IA) is evident in all three countries, though the dynamics and mechanisms differ substantially.

In Belarus the situation is the most severe: already in Lukashenko’s first years in office (by 1996) university autonomy fell below even late-Soviet levels. University rectors began to be appointed by the president. After 2020 a new control mechanism was introduced — the position of vice-rector for security and personnel, drawn from the security services. Since 2022 amendments to the Education Code placed all universities in the country — including private ones — under the direct control by the Ministry of Education.

In Russia the university autonomy indicator declined more slowly and fell to late-Soviet levels around 2012, when the updated Education Law rendered university structures unitary in legal terms: only the university itself possesses the status of a legal entity, while faculties and subdivisions lost independent legal capacity. Rector elections, already closely monitored by the state since the 2000s, have since 2021 been conducted by special external commissions whose results are approved by the ministry.

At the same time, coordination centers for countering extremism and terrorism were established at major universities of all Russia’s regions. Every year these centers train about 10,000 specialists in extremism prevention. Over time, this system may now have trained roughly 40,000 people — approximately one for every 100 students. (For scale: this exceeds the number of KGB secret informers in the Soviet era. According to declassified documents of the KGB of the Ukrainian SSR, in 1987 there were 81,000 informers for 39 million adult residents of Ukraine — about 1 per 500 people).

In Ukraine, unlike Russia and Belarus, full rector elections remain in place, and the Ministry of Education and Science has even taken steps to prevent rector terms from being “reset” during university reorganizations. The decline in institutional autonomy (IA) is mainly driven by economic problems tied to military spending and the hryvnia’s collapse. This has led to increased centralization: reduced departmental independence and a growing gap between regional and central universities. The number of state universities is rapidly shrinking through mergers: from about 347 in 2022/2023 to roughly 300 by 2025, with forecasts predicting only 100 by 2038 due to wartime demographic decline. A cautious step toward liberalization was taken with pilot financial autonomy programs launched in four universities, though their outcomes are still unclear.

Physical threats to campuses and to their integrity (CI) — including surveillance, raids, and destruction — prevent scholars and students from focusing on research and open discussion of ideas. Interference into campus life destroys the intellectual environment and undermines academic freedom.

Up-to-date videos on science during wartime, interviews, podcasts, and streams with prominent scientists — subscribe to the T-invariant YouTube channel!

In Russia control occurs through vice-rectors for security, informant reports leading to FSB searches and seizures. Some universities use video surveillance in lecture halls to monitor loyalty. There have been attempts to ban students from keeping of “foreign agent” books in dormitories. Another example occurred in Yakutsk in 2024 , when the director of a university library was fined for making books (apparently by Heinrich Böll) available that were deemed linked to an “undesirable” organization (the Heinrich Böll Foundation).

In Belarus security services are embedded in university governance: surveillance via cameras, searches, phone checks, and students taken to police stations. Campus autonomy has effectively disappeared.

In Ukraine CI has fallen primarily due to shelling and strikes: nearly half of universities have been damaged by missiles and drones. According to the World Bank’s fourth report on the cost of war damage in Ukraine (RDNA4), released nearly a year ago, the cost of repairing the war damage to higher education is estimated at about $3 billion, while restoring Ukrainian research infrastructure will require $15 billion (the SAR report contains some inaccuracies in these figures).

The situation is exacerbated by evacuation: of more than 2,000 surveyed Ukrainian scholars, 37% changed their place of residence during the war, more than half of them twice. This contributed to the sharp drop in CI, especially after 2024.

Academic freedom suffers regardless of the reasons for violating campus integrity. Responsibility is usually assigned to the authorities, but in the case of invasion it lies with the aggressor. Thus, during wartime, AFi partly ceases to be an indicator of internal policy quality.

Restrictions on academic mobility (AED) are also intensifying in all three countries, but in Russia and Belarus primarily due to international sanctions, and in Ukraine due to mobilization restrictions.

Russia has been excluded from several international research collaborations (e.g., CERN), withdrawn from the European Higher Education Area (Bologna Process), and stopped prioritizing toward international publication databases Scopus and Web of Science. About 50 countries are designated “unfriendly” in Russia, and scientific cooperation with them requires approval from a special government commission. Since 2025, a law requires scholars to report to the FSB on all foreign participants in research projects.

Belarus, which joined the Bologna Process on its second attempt in 2018, was excluded from it in 2022. Cooperation is being developed mostly with Russia (the number of scholarships for Belarusians to study in Russia grew 18-fold from 2018 to 2023, reaching 1,300 per year) and China, with which 10 new joint programs have been launched.

In Ukraine the 2022 restriction on men leaving the country means fewer than 20% of scholars can personally participate in international events. According to a survey in the SAR report, this has also created a strong gender asymmetry: three-quarters of participants in such mobility are women.

Brain drain is the flip side of all these processes. Many scholars and students choose to leave countries experiencing social cataclysms.

In Ukraine, according to the aforementioned survey, about 20% of academic staff have left either the country or scientific activity. The number of Ukrainian students studying abroad rose from 75,000 in 2021/2022 to 109,000 in 2023 and 115,000 in 2024. At the same time, there is no breakdown of where this increase comes from. It may be explained not so much by students arriving from Ukraine as by refugee schoolchildren who, upon finishing school, enroll in foreign universities (the report, citing the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine, states that 345,000 schoolchildren were studying abroad in 2025, though higher estimates exist).

For Russia, the report cites a lower-bound estimate of those who left in 2022–2023 based on changes in publication affiliations — at least 2,500 people. Extrapolating from this figure, total losses among scientific personnel in Russia during the full-scale war can be estimated at roughly 2%. Those leaving are typically among the stronger specialists.

For Belarus the report provides no quantitative estimate of the “unprecedented wave” of academic emigration, but states that it likely numbers in the thousands, and the Science at Risk alone has financially supported over 560 departing scholars and students.

Restrictions on freedom of thought and expression inevitably emerge both in authoritarian countries — imposed from above — and in democracies at war — through self-censorship originating from citizens themselves.

In Russia, over the years of Putin’s rule, a multilayered system has been built to impose and protect a military and political narrative. Among other things, it includes:

- direct prohibitions on speech (“fakes,” discrediting the army, justifying Nazism/terrorism, distorting the USSR’s role, LGBT propaganda);

- extrajudicial website blocking and prohibition of accessing or searching for banned information;

- deprivation of rights for certain categories of people (foreign agents, undesirable organizations, those listed as extremists and terrorists);

- persecution for expressing “incorrect” attitudes toward these groups;

- politically motivated persecution — from searches, dismissals, and administrative pressure to fabricated criminal cases of treason with closed trials and sentences of up to 20 years or more.

Assessing the scale of repression is difficult due to fragmented information. OVD-Info and Mediazona reported that in 2022–2023 about 8,500 people faced administrative persecution for anti-war positions, more than 800 faced criminal charges, and over 500 faced disciplinary measures. In relation to the adult population, this amounts to about 43 people per million per year.

It is harder to obtain data on persecution within the scientific community. The SAR report compiles data from OVD-Info, Molniya, Groza, Novaya Gazeta, and T-invariant’s Chronicle of Persecution of Scholars. According to T-invariant data updated in December, 98 individuals were added to the chronicle in 2023–2025. In relation to Russia’s scientific community size (750,000 scientific and technical staff in research institutes, university instructors, and graduate students), this yields the a similar rate — 43 per million per year. However, given the inevitable incompleteness of open-source and private communication data, as well as some decline in persecution intensity over the war years, it can be said that the scientific community has been affected more severely than society as a whole.

In 2025 the repressive toolkit further was expanded with a law requiring university and research institute employees to obtain security service permission before any publication — from scientific articles to public lectures. This measure most closely resembles to traditional censorship and was introduced under the pretext of protect secrets. However, the repressive system is not military censorship. Its goal is not to preserve secrets but ideological control over the political narrative to ensure the state’s monopoly on truth and unimpeded indoctrination of the population.

All these measures extend far beyond academic freedom alone, but among other things they cause declines in freedom of expression (ACE), freedom to disseminate scientific ideas (AED), and freedom to research and teach (FRT).

In Belarus freedom levels have been lower than in Russia since the late 1990s. Even the main security service has retained not only continuity with its Soviet predecessor but also its name — Committee for State Security (KGB). While Belarus’s Republican List of Extremist Materials appeared almost simultaneously with Russia’s Federal List — in 2007–2008 — administrative penalties (including arrest) for reading such materials was introduced in Belarus as early as 2010. Belarus lagged in creating a registry of extremist formations — it was imposed only in 2021. Work is already underway to unify the registries of extremists and corresponding materials between the two countries.

Interestingly, tracking of registries’ growth since 2021 shows almost strictly linear increases (R² = 0.98–0.99): the number of foreign agents grows by an average of 187 per year, the list of undesirable organizations — by 48 per year (and lately increasingly includes universities), Belarus’s list of extremist formations — by 75 per year, its Russia’s equivalent grew by 1,100 per year until 2023 and then accelerated to 2,900 per year. The linear growth of repressive registries indicates that their expansion is determined primarily by the capacity of repressive units, for which the corresponding figures are set as targets.

Ukraine, as the victim of aggression, has no need to construct a complex system to justify its position. However, justified outrage is also channeled into the demonization of everything Russian and the glorification of controversial pages of its own history. Although the government has at times tried to restrain these tendencies, it ultimately could not resist the public demand fueled by ongoing aggression.

Since 2017 the import of Russian books into Ukraine was banned. After the 2022 invasion, the National Academy of Sciences and the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine strongly recommended that scholars cease joint work with Russian colleagues, and all institutional cooperation with Russia was severed. The law does not prohibit co-authorship with Russians in a personal capacity, but it can be perceived as disloyalty and lead to loss of funding, career restrictions, and disciplinary measures. Such publications remain under close review by the Ministry.

The 2025 law on national memory steers scholars toward unification of narratives, which can be regarded as a form of state-sanctioned self-censorship. While often justified by wartime threats, when applied with strict formalism it significantly reduces the level of academic freedom.

Lessons in Countering Degradation

Authoritarian rule restricts civil liberties, which inevitably reduces academic freedom and leads to a decline in a society’s intellectual potential. This process weakens the autocrats’ capabilities but also diminishes society’s chances of overcoming dictatorship. Therefore, countering aggressive dictatorships must account for the non-trivial relationship between the level of science/academic freedom and the strength and resilience of such regimes.

An authoritarian regime prone to external aggression undermines the freedoms of its targets long before an attack (or even without one) by sharply strengthening security motives in the public consciousness of neighboring societies — motives that always stand in opposition to freedom. Preserving domestic societal freedom, including academic freedom, despite external threats should be considered an important element of security.

Undermining freedom by provoking fear and hatred is one of the dangerous mechanisms by which authoritarian regimes inflict damage. Figuratively speaking, unfree countries can “infect” their neighbors with unfreedom. The decline of academic freedom during war should be regarded as indirect damage of military action. If a society begins to sacrifice freedom out of fear and mythmaking, a potential aggressor scores an important victory without even entering battle.