The development of large language models has dramatically improved the quality of machine translation and made such tools widely accessible throughout the world. These technological advances coincided with the onset of Russia’s full-scale military aggression against Ukraine. As a result, a phenomenon we can characterize as academic looting has emerged and become widespread. This is the subject of today’s issue of Plagiarism Navigator.

Previously in Plagiarism Navigator

- Episode 1: China–Ukraine–Poland — The story of a Chinese scholar who defended a dissertation in Kharkiv, cobbled together from Russian-language works translated into Ukrainian.

- Episode 2: Russia–Tajikistan–Iran — The case of Iranian scholars obtained degrees in Tajikistan (2011–2013) under Russia’s VAK system.

- Episode 3: Russia–Serbia–Turkey–Switzerland–Lithuania — The tale of a Serbian academic who resorted to buying co-authorships and outright plagiarism.

- Episode 4: Russia–USA–Brazil–UK–Switzerland-India — A professor at Sechenov University who infiltrated an Iran-Iraq publication scheme in top Western journals, creating a lucrative paper mill within his own institution.

- Episode 5: Russia–Ukraine–Romania–India — The story of Andriy Vitrenko, Ukraine’s former deputy Minister of Education and Science, whose dissertation and academic papers were found to contain plagiarism.

- Episode 6: Russia–Ukraine — The tale of how wartime cross-border plagiarism became a commercialized scheme to boost academic metrics for Russian and Ukrainian scholars.

- Episode 7: Russia–Tajikistan–France — The journey of a humble Tajik accountant who rose to become the head of the country’s Academy of Sciences.

- Episode 8: Russia–Poland–Australia. The story of publications in Australian journals involving the Zhukov–Fedyakin family clan from RGSU, former Minister of Culture Vladimir Medinsky, former RGSU Rector Natalia Pochinok, and a Kuban engineer.

Recently, it was discovered that an article in the journal Izvestiya Kabardino-Balkarskogo nauchnogo tsentra RAN (Proceedings of the Kabardino-Balkarian Scientific Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences) from 2024, devoted to the features of digital economy development, is a literal Russian translation of part of a dissertation completed a year earlier in Kyiv in Ukrainian. Notably, the author of this article is Doctor of Economics, professor, chief research fellow and head of the Laboratory of Problems of the Level and Quality of Life at the Institute of Socio-Economic Studies of Population, which is part of the FCTAS RAS (Federal Center of Theoretical and Applied Sociology of the Russian Academy of Sciences), as well as Honored Scientist of the Republic of Dagestan — Sergey Dokholyan*. How could this happen? A respected scholar, member of the editorial board of that very journal — and of eight other academic journals — and a permanent member of a Russian Academy of Sciences expert council, simply downloaded someone else’s work in Ukrainian from the internet, translated it into Russian, and passed it off as his own?

At the same time, we found that the same Ukrainian dissertation also was used as for co-authors from Chechen and Dagestani universities. However, they translated a completely different fragment of the text into Russian and published it under their own names.

Top news on scientists’ work and experiences during the war, along with videos and infographics — subscribe to the T-invariant Telegram channel to stay updated.

In both cases, the authors, their affiliations, the journals, and the text fragments differ — yet the source of “scholarly creativity” is the same. It remains only to assume that a third party was involved here, one that deliberately prepared ready-made manuscripts and offered them to interested authors. This is precisely how paper mills — factories of fake scholarly publications — operate. Apparently, Dokholyan and the scholars from Makhachkala and Grozny simultaneously — without coordinating with each other — used such a factory’s services.

What is the scale of translation plagiarism in Russian-language academic journals, particularly from Ukrainian-language dissertations freely available online? What is the history of this phenomenon? What is its geographic scope? What is the social status of the translator-plagiarists? To answer these questions, T-invariant, using modern natural language processing (NLP) tools, cross-referenced a collection of Ukrainian-language dissertations (over 150,000) against the texts of Russian-language publications (more than three million) for the period 2012–2022 inclusive. We selected only articles containing large-scale translated borrowings from a Ukrainian-language dissertation and were published after the defense date of the source dissertation. In the end, just over one hundred Russian-language publications were identified.

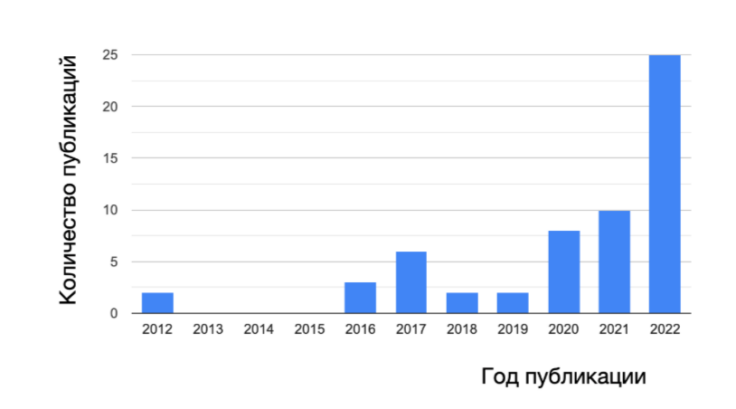

From this set of about one hundred publications, we excluded those whose authors were affiliated with Ukrainian universities. Ultimately, only 58 articles published in Russian-language journals remained. The distribution of these publications over time is shown in the figure.

The graph shows that before the emergence of publicly available machine translation tools in the early 2020s, translation plagiarism did not gain traction. As expected, the boom in cross-border translation plagiarism began with the dramatic improvement in machine translation quality and the widespread adoption of accessible tools.

Among the fifty-eight publications selected for further analysis, there are two by authors affiliated with Belarusian institutions and one each from Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, and China. Otherwise, the geography of the plagiarists is extremely broad — from Vladivostok to St. Petersburg. The social status of the plagiarists is equally diverse: from students and graduate students to prorectors and rectors. There is only one rector — from Vitebsk State University (Belarus). A prorector from RGSU (at the time of publication) also stands alone. However, there are plenty of associate professors and full professors among the authors. Some affiliations in the selected publications are quite exotic and hardly expected in academic articles. The most striking example is Mikhail G., deputy brigade commander for logistics, chief of logistics of 77th Anti-Aircraft Missile Brigade. His publication coincided with the onset of full-scale military aggression, and just a year later, for “achievements” far from the academic sphere, the anti-aircraft missile brigade was awarded the honorary “Guards” title.

Up-to-date videos on science during wartime, interviews, podcasts, and streams with prominent scientists — subscribe to the T-invariant YouTube channel!

A telltale sign of paper mill activity — random co-authorships — appears only in 2021. Already the following year, a stable connection emerges between paper mills and a scientific journal publisher. Of the twenty-five publications from 2022, fifteen appeared in the journal Upravlenie Obrazovaniem: Teoriya i Praktika (Education Management: Theory and Practice), which is included in the VAK list [of journals approved for publishing dissertation results. — T-invariant]. The year before, there was only one such publication out of ten. The phenomenon of paper mills merging with — or effectively taking over — academic journal publishers was noted in a recent large-scale study of the international market for fake scientific papers (5). Incidentally, according to the official position of the leadership, the Unified State Register of Scientific Publications (EGPNI), where Russian scholars will be required to publish, will be expanded to include almost all journals on the VAK list. Moreover, publications in this VAK list will receive priority over prestigious foreign journals. Observing how easily burgeoning paper mills conquer relatively weak journals, we can confidently say that prioritizing domestic journals on the VAK list will lead to even more chaos in the Russian academic landscape.

Even taking into account all necessary caveats, adjustments, and extrapolations, the phenomenon of translation plagiarism from Ukrainian-language sources has not yet reached catastrophic scale. However, the dangerous trend persists, and if adequate countermeasures are not taken in the coming years (and even worse — if low-quality domestic scientific output is prioritized), we may be in for turbulent times.

*According to Dissernet data, Sergey Dokholyan defended his doctoral dissertation in 2001, in which large-scale improper borrowings were later discovered. Since then, he has directly participated as a dissertation supervisor or official opponent in the defense of at least fifty dissertations in which large-scale improper borrowings were also found. It is therefore unsurprising that twelve of his doctoral students have already been stripped of their academic degrees for plagiarism.