For residents of Eastern Europe war is not just a word from textbooks and news anymore. It invaded their homes and their destiny, became part of their daily routine. Ariel University researcher Victor Vakhshtein, in his open lecture at the Free University, proposed to consider different situations in which war and ordinary life are separated or not separated by time and distance, and to understand what sociologists can and cannot tell us about it.

The war is “drawn out by the fabric of everyday life”.

This German philosopher Bernhard Waldenfels’ metaphor can describe a situation in which war and everyday life are separated from each other in time. The war has been left in the past, but it is a very recent past. It is still visible and audible, it influences on the people’s behavior. The lecturer himself observed these manifestations while working in the Balkans (in northern Albania, western Bosnia and eastern Croatia) 10 – 15 years after the end of the war: “This is a strange feeling of a half-healed wound. The war has not gone away, it is still here, it still determines whole political life, continues to structure everyday practices, but as if it was blurry, wrapped in the fabric of everyday life.

10 – 15 years after the end of the war, the bridge connecting the past war and everyday life most often turns out to be cultural or collective memory. Sometimes it may seem to us that collective memory is silent and the topic of war is a taboo. Victor Vakhshtain is sure that even in this case the war affects everyday life. He cites an example from a play by Israeli writer Gila Almagor, in which parents who survived the Holocaust try to avoid the topic in every possible way. Nevertheless, the presence of the war and the Holocaust is evident in every phrase they utter, in every action they take. A similar reaction can be observed among older people in Russia who survived the war but do not want to remember it. The phrase “food is not about pleasure, it is about eating” is familiar not only to the heroine of the play.

Experience of peaceful life in the reality of war

Neither volunteers at the front, nor those who are called up to the front, nor residents of occupied territories, nor refugees start their military life from scratch: they all approached the war with already existing life experience. They rely on their experience received in a past life.

Sometimes this experience is consciously used. For example, at the end of World War II, America began producing T12 and T13 Beano hand grenades, which were exactly the size of a baseball: not all young conscripts had experience throwing grenades, but most of them had experience playing baseball. Here the body becomes the mechanism of transfer. All our experience, our skills and abilities are reflected in the way we speak, walk, open doors, etc. And all this can be quickly reconfigured for a new reality.

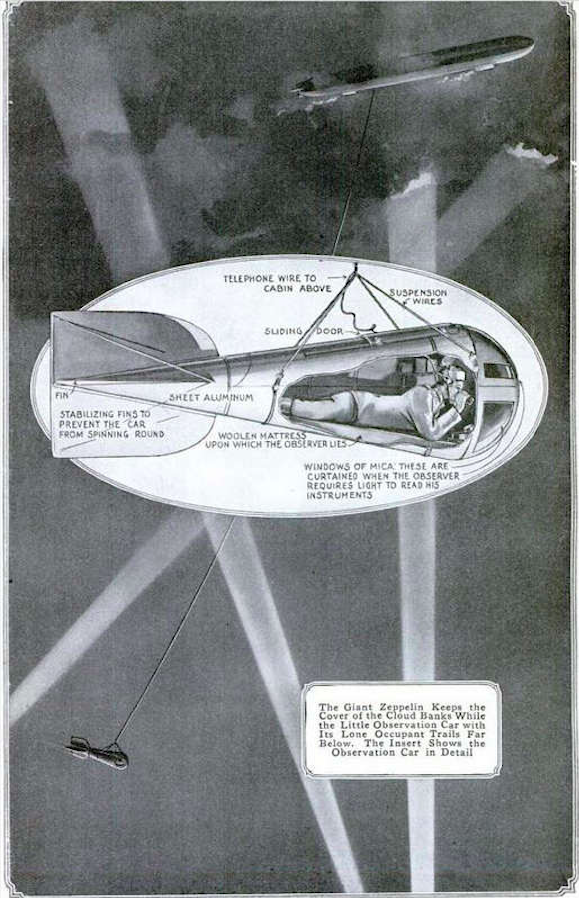

There are many historical examples of how peaceful habits influence the advancement of military innovation. One such example is the observation (or spy) gondolas common during the First World War. Such a gondola was a special basket, which was lowered from the airship on a long cable. They were used for intelligence purposes. At the same time, the airship itself was inaccessible to enemy artillery, unlike the military in the gondola. Working there was not only dangerous, but also extremely uncomfortable. The inventors feared that the soldiers would have to be driven onto this gondola under pain of execution. However, the crew members of the aircraft willingly carried out the mission assigned to them, since this was the only place on the airship where smoking was allowed.

“War is out there somewhere”

But what happens if war and everyday life are separated not in time, but in space, when ordinary people can only learn about war through the media? This seems to be the modus operandi of most modern wars, Vakhstein believes. Sociologist Hugh Gastersen connects this relationship between war and everyday life with the tradition of imperial wars: empires always fight somewhere on territory that they consider theirs, while it can remain unknown to inhabitants of these empires.

History has known many such examples. For instance, some residents of Australia and New Zealand learned of the existence of Gallipoli and Turkey when their countries lost 8,709 and 2,721 people there, respectively. Otherwise, they would not have paid attention to the Battle of Gallipoli (a military operation near the coast of Turkey, which lasted from February 19, 1915 to January 9, 1916). According to Vakhstein, refugees should be included in this same mode. Although they are territorially separated from the war, they continue to experience the war that is taking place in their homeland.

The main mediator, the bridge in this mode is still the media, through which we learn news from the front and form our own idea of the war. It is logical that not only the media influence on our perception of war, but also wars influence on the media. Thus, according to the lecturer, the Crimean War (1853-1856) played a key role in the modern “media race”. Until the beginning of the 19th century, the English public learned about the war primarily thanks to enthusiastic essays appearing in newspapers from time to time. These essays appeared about a month after the real battle, after the same period, death notices also came.

But in 1854, William Russell, a British correspondent for The Times newspaper, came up with the idea of using the telegraph to transmit his materials. Of course, you cannot send a detailed essay by telegraph, only news or a short report. So he described that the attack near Balaklava failed, and a certain number of brilliant British officers and soldiers died due to a command error. For the first time in history, parents learned about the death of their children from the newspaper the day after the incident. Although official confirmations, as well as official funeral notices, still came only a month later.

Parliament was furious and demanded an answer from the prime minister. The Prime Minister himself didn’t know anything yet. Only the camera could resist the telegraph in the fight for the reader. The first official war photographer, Roger Fenton, was sent to the same Crimean War. Although the cameras of that time did not allow to shoot battle scenes. Therefore, Fenton’s photographs look quite pastoral: they represent either scenes of preparation or the life of soldiers. Nevertheless, this is how war photojournalism was born.

Before this war, none of the inhabitants of England had the feeling of war in real time, they were separated from the news from the front by both space and time. Today, the media, if they do not make us real eyewitnesses of events, then create the illusion of involvement due to synchronization.

War as a premonition

In this case, everyday life and war are separated as actual and potential. There is no military action. Nevertheless, you wake up and go to sleep with the feeling that war is inevitable. It is precisely this modus that can be attributed to the life of many American families during the Cold War, in which fathers, preparing for the upcoming exchange of nuclear strikes with the USSR, built bomb shelters in their backyards.

Sinisa Malešević, a professor at the University of Dublin who studies the sociology of war, examined how children’s toys changed in the run-up to the First World War. Toys became militarized and prepared children for war, in fact, even before it began. The main bridge between everyday life and such a war is propaganda. At the same time, propaganda can both try to mobilize the population and calm it down, for example, by refusing to call the war by its name.

War is actually an everyday life

War and everyday life are not separated either in time or in space. Everyday habits subordinate the logic of war (the desire to smoke outweighs the risks of being killed), and vice versa, the logic of war subordinates everyday life (you choose your route to work based on the likelihood of shelling). In such a situation, there is simply no bridge between war and everyday life: the war is an everyday life. It is about this mode that the least number of scientific works have been written. And most of their authors are not sociologists, but ethnographers.

Why do sociologists study war so little?

Sociologists pay great attention to military service as a social institution, everyday life in the army, conscription and the militarization of society. But they don’t actually consider the war itself. And, according to Viktor Vakhshtein, this has its reasons.

The English philosopher Thomas Hobbes wrote in his treatise “Leviathan” that human nature contains only a few basic constants: the thirst for goods (both material and intangible), the fear of being killed, some rudimentary common sense and interest “in higher spheres.” But what is missing, according to Hobbes, in human nature is an innate fuse that would prevent one from starting a war against a neighbor. There is no “natural law”, no solidarity. Therefore, the war of all against all is the natural state of mankind. But at some point, thanks to rudimentary common sense, people enter into a social contract, that is, they exchange their natural right to kill for the civil freedom not to be killed. On this basis, according to Hobbes, society arises. Before the social contract, there is no society. There is a “multitude” (that is, a set of individuals at war with each other). Therefore, war is either a pre-social or extra-social phenomenon.

Since sociology owes its emergence precisely to the “Hobbesian problem” of social order, war is perceived by the classics of sociology as the collapse of social order, and therefore is not the subject of study of the new science.

“This approach has led to the fact that sociology is the only discipline that “did not notice” the Second World War,” notes Viktor Vakhshtain. — The experience of concentration camps, the experience of the world war turns the axioms of psychology and philosophy upside down; in economics, under its influence, the axiom of rationality is abandoned, and only in sociology, with the exception of some marginal authors who demanded to be closer to reality, no one is interested in war.

Perhaps the only exception here is Max Weber, who understands “social” not as “order and solidarity,” but as the totality of rational actions of individuals. And then the war begins to take sociological shape. “But with this approach, everyday life is left out,” the lecturer notes. — Weber is much more interested in how military discipline gives rise to modern, rational bureaucracy. He is interested in how warring armies orient their actions towards each other, how they try to predict each other’s actions, and how this ultimately leads (or does not lead) to a peace treaty.”

“Both in the first (there is no war at all for sociology) and in the second approach (war turns out to be a highly rational enterprise), the everyday life of war is beyond the scope of interest,” notes Victor Vakhshtein. — Even Alfred Schutz, the Austrian sociologist who first drew attention to the problem of everyday life, writes nothing about everyday life and war. Although the war literally rolled over his life.

Why is it important: the war or the “Special Military Operation“?

However, Schutz identified six parameters that define everyday life. Among them are a specific perception of time (the cyclical time of workdays), mechanisms for suppressing doubt – what can and cannot be doubted (otherwise you will be afraid to leave the house, and even more so it is impossible to go on the highway), an attitude of consciousness that excludes reflection and interpretation etc. According to some of Schutz’s parameters, war is at odds with everyday life, but according to others, it completely coincides with it. This makes it possible, on the one hand, to look at war as an event that breaks apart everyday life, and on the other hand, how the extraordinary becomes everyday life (everyday life of war).

The development of Schutz’s ideas led to the emergence of the theory of frames. When an extraordinary event occurs in a person’s life, he selects qualifications for him, places him in a special cognitive cell. This allows not only to recognize and interpret the event, but also suggests how to act. Vachstein compares the frames that we encounter in everyday life with “exe” files: when unpacked, they prompt us with an algorithm of actions. That is why it is of fundamental importance whether you call what is happening in Ukraine a “war” or a “military operation”. Different names, different interpretations entail different actions of subjects.

– In fact, the everydayization of the war is the embedding of the event of the war into some more understandable, familiar, repeatedly tested interpretation.

Viktor Vakhshtain sees several ways of making war everyday. For example, there is appropriation. We try to find the familiar in the unfamiliar and act accordingly. The lecturer, who recently lives in Israel, had to sit in bomb shelters six times over the past two years:

– What do I see there? A variety of forms of manifestation of routine life. Someone brings speakers with them, someone brings a watermelon, people get to know each other, communicate, and fragments of the Iron Dome rockets fall 150 meters from us. The behavior of most people in the bomb shelter is an example of appropriation.

The phenomenon opposite to appropriation is reframing, an ordinary event is disguised as a military one.

The example of reframing that Victor Vakhshtain gives is almost shocking. On February 19, 1942, sirens wailed in the Canadian city of Winnipeg, at 6.30 a.m. bombers with a swastika appeared in the sky, dropping bombs. After which 3.5 thousand soldiers in German uniforms entered the city. A couple of dozen officials, priests and journalists were sent to a concentration camp, which was set up on the territory of a local golf club. In fact, no bombers bombed the city – it was an imitation of an attack; bomb explosions on the ground created pyrotechnics. There were no Germans among the attackers; the entire “invasion force” consisted of Canadian soldiers in disguise. This was done to encourage residents to help financially in the fight against the Nazi regime. But many Winnipeg residents took the “invasion” at face value. And they began to hand over the Jews, they began to report to the occupiers that they were “unreliable.” Some people rushed to sign up for the police, some were interested in how to join the SS.

“One way or another, the theory of frames assigns a little more weight to those models that already exist in our heads,” Vakhstein shares his opinion. “It is assumed that our collective ideas are so stable that they can grind through literally anything, even war.”

Filippov’s theory – the theory of social events – proposes to single out a separate class of events that cannot be framed. Alexander Filippov, a Soviet and Russian sociologist, compares such events to something that “burns through the fabric of your everyday life.” You don’t have any cognitive slots where you can put what happened. There are no words to describe it. In such a situation, we cannot discuss the mechanisms of routinization. We study what has the potential to destroy routine to its core. Schutz’s six variables no longer work: you have fallen out of everyday life.

The frame analyst will likely assure you that this state is only temporary. Social life is structured in such a way that everyday life is its most fundamental layer, even in conditions of war, in conditions of monstrous deprivation. A new everyday life and new practices are being formed. And here the difference between everyday life and normalization is most clearly visible.

Routineization is when something unthinkable just yesterday becomes routine. Normalization is when something unthinkable just yesterday is described in the public space as something completely normal. Barbecues in a bomb shelter and the thoughts “If it weren’t for the shelling, we wouldn’t have talked” – this is normalization. The new road to work, taking into account shelling, is an everyday occurrence. Using the phrase “we work the block” to describe the bombing of residential areas is normalization. Routineization is often a new set of actions, and normalization is a new way of describing something.

As a result, when discussing the fifth mode, we can first of all talk about everyday life, about how something that we couldn’t even imagine yesterday needs to be included in routine today.

Unfortunately, the war today is happening too close to all of us. We see from our own experience both the processes of everyday life and the processes of normalization. Can such lectures change anything in this situation? Probably not. But they, without a doubt, help to understand what is happening, help to look from a new, unexpected side. This means that they will help someone make the right decision, someone to maintain their sanity, and someone – humanity.

Text: Yulia CHERNAYA

Books recommended and mentioned by the lecturer for those who want to understand the topic deeper:

Maurice Halbwachs, Social Frames of Memory

Gila Almagor, play “Summer of Avia”

Hugh Gusterson Drone: Remote Control Warfare

Siniša Malešević The Sociology of War and Violence

Mary Douglas. Purity and danger

Brad West. Towards a strong program in the sociology of war, the military and civil society

Thomas Hobbes. Leviathan or Matter, the form and power of the state, ecclesiastical and civil

Thomas Schelling. Conflict strategy

Erving Goffman, Frame Analysis. Essay on the organization of everyday experience

Yulia Chernaya 11.09.2023