The seventh essay in the “Creators” series is dedicatedIgor Sikorsky , an outstanding engineer, pilot, one of the founders of modern aviation. He was born in Kyiv. He built airplanes and helicopters in St. Petersburg and America. And wherever he was, there was a sky above all cities, countries and continents, in which he laid his “air paths”. In the “Creators” project T-invariant together with RASA (Russian-American Science Association) continues to publish a series of biographical essays about people from the Russian Empire who made significant contributions to world science and technology, about those to whom we owe our new reality.< /strong>

Kyiv. Early years

Igor Ivanovich Sikorsky was born on June 6 (May 25, old style) 1889 in Kyiv, in the family of a famous psychiatrist, professor of the department of mental and nervous diseases at Kyiv University Ivan Alekseevich Sikorsky (1842-1919) and Maria Stefanovna Sikorskaya, née Temryuk-Cherkasova .

Ivan Sikorsky was a doctor of medicine, head of the department at the Kyiv University of St. Vladimir. In 1896, he founded the journal “Issues of Neuropsychic Medicine and Psychology.” He wrote a treatise “On Stuttering” and worked extensively on treating children with mental disorders.

Ivan Sikorsky was a Russian nationalist. He participated in the work of the Kyiv Club of Russian Nationalists. In 1913, as a medical expert, he supported the prosecution in the Beilis case , for which he was subjected to harsh criticism and accusations of anti-Semitism. He took these events seriously, fell ill and was unable to teach. Igor Sikorsky loved and always supported his father. He believed that his father had been slandered. But, as the documents from the Beilis case show, the great inventor was wrong about this. Professor Vladimir Serbsky wrote that Sikorsky “compromised Russian science and covered his gray head with shame” (1).

Maria Stefanovna Sikorskaya received a medical education, but devoted herself to raising five children, the youngest of whom was Igor Sikorsky. Maria Sikorskaya told children a lot about the inventions of Leonardo da Vinci. This became a source of inspiration for Igor, who, as a young man, designed his first flying machine (2). It was a simple model with a propeller driven by a rubber band drive. Of course, the model could only fly straight up and was uncontrollable in flight. But it took off.

In 1900, Igor Sikorsky entered the First Kyiv Gymnasium. It was a famous educational institution. Among its graduates were the artist Nikolai Ge, the economist and Minister of Finance of the Russian Empire Nikolai Bunge, the historian Yevgeny Tarle and many other cultural and political figures. But Sikorsky himself was not very attracted to classical education. Following the example of his older brother Sergei, in 1903 Igor became a cadet at the Naval School in St. Petersburg. This school trained shipbuilding engineers, but even here Sikorsky did not feel at home: he wanted to build not ships, but aircraft. And after 3 years he left the school.

Cadet Igor Sikorsky (on the right) with his brother Sergei and sisters Lydia, Olga and Elena https://static.ukrinform.com/photos/2019_05/1558716605-206.jpg

Following the advice of his father, Igor Sikorsky went to Paris, where he studied at the Duvignot de Lanno technical school for six months. It was a good time in Sikorsky’s life. At school, many students and teachers were literally fans of aviation. Six months later, Sikorsky returned to Kyiv and entered the Kyiv Polytechnic Institute. Here Sikorsky continued his work on creating heavier-than-air aircraft.

There was an aeronautics circle at the Kyiv Polytechnic Institute and Sikorsky became a member of it. The circle was led by mathematician Nikolai Delaunay and electrical engineer Nikolai Artemyev. He was recommended as a professor at KPI by the famous mechanical scientist Nikolai Zhukovsky, one of the founders of hydro- and aerodynamics. Igor Sikorsky later wrote about Zhukovsky in connection with aerodynamic research: “The first laboratory of this kind was opened in Russia for many years before such institutions appeared in other countries. It was the Aerodynamic Institute in the village of Kuchino near Moscow. It was founded by D. P. Ryabushinsky. Moscow University professor Nikolai Egorovich Zhukovsky, who was one of the first scientists to shed light on this hitherto unknown area of technology and science, took part in his scientific work.” Sikorsky understood perfectly well that science could save a lot of time for an engineer who builds an aircraft; it could become his eyes, and without it he would have to work in the dark by touch.

In 1908, Sikorsky traveled with his father to Berchtesgaden, Germany, where he learned about the flights of brothers Wilbur and Orville Wright. Throughout 1908, Europe was shaking a little with excitement. Wilbur Wright flew over Paris: the airplane made circles and loops, lifted passengers into the sky (one at a time) and even a cameraman. This was not the first heavier-than-air aircraft, but no one had managed to achieve such controllability and carrying capacity before.

Sikorsky never graduated from any higher educational institution. In this he is a bit like the computer geniuses of the 1970s: why learn anything from people who don’t understand anything about what interests you? You just need to build airplanes or computers and gradually gain experience. But Sikorsky nevertheless received an engineering diploma – in 1914 at the St. Petersburg Polytechnic Institute without defending his diploma for the creation of multi-engine airships.

Dream of a helicopter

In 1907, the French designer Paul Cornu took off from the ground for the first time on a helicopter: he rose 30 cm on his device. But there was still no flight. Not because he rose so low, but because his aircraft was uncontrollable.

Cornu’s helicopter was a rectangular frame with two propellers mounted on opposite sides. (This is the so-called coaxial helicopter design – many years later such machines were also built, they actually flew. Already in our time, two more propellers were added to the devices, and the result was the most popular drone model in our time – a quadrocopter). The engine and the tester himself were located on the frame. When the propellers were launched, the device rose to the ground. Its power was enough to lift its own weight and the weight of the tester. But for a real flight this is not enough. It is not only necessary to rise and fall. You need to fly forward, make a turn, but Cornu’s helicopter could not maneuver. The Wright brothers’ airplane could do all this, and it was clear that helicopters still had to learn all this.

What is the difference between a helicopter and an airplane and why everything is much more complicated with a helicopter. An airplane has a glider – it can fly even with the propeller turned off, although not for long, but it can. But if a helicopter’s propeller turns off, it simply falls. That is, the airplane maneuvers due to small changes in the wings and tail. In a helicopter, the main rotor must be responsible for all this: there is simply nothing more. He keeps the device in the air and maneuvers.

In general, when the Wrights built their airplane, they flew it for quite a long time without a motor: it was a pure glider , in which they worked out precisely the maneuvers: up and down (or pitch), yaw – turns left and right in the horizontal plane, and roll on the left and right wings. Just the roll allows you to turn around in the air.

The Wrights invented elevators. With their help, ascent and descent were carried out. The elevator controlled additional “wings” that were attached to the lower wing of the biplane and turned up and down. The yaw was controlled by the tail rudder. The roll was carried out by a slight deformation of the wings: if the wings skewed to the left, the airplane turned to the left, and vice versa.

The Wright brothers’ glider flies without a motor, but it can already maneuver in the air. https://habr.com/ru/companies/macloud/articles/566418/

And then they installed a light motor on the glider. And the airplane really flew. When maneuvering, the propeller always operates in approximately the same mode; at least, it does not need to be turned. The entire maneuver is accomplished through changes in the wings and tail.

Most of the Wright brothers’ ideas were taken up by many engineers. They were actively developed. But all these bold ideas and fine adjustments did not help much in creating the helicopter. It doesn’t have wings.

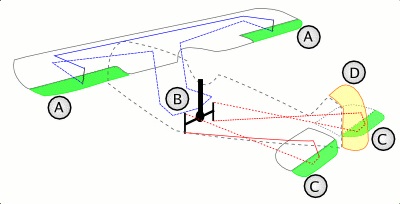

Flight control diagram of a modern aircraft. A) – ailerons – wings controlled by the steering wheel B). They provide left and right roll and turn in the air. The Wrights did not have ailerons; roll was provided by wing deformation. C) – tail wings (they are controlled by elevators B). They are responsible for ascent and descent. The horizontal rudder D) is responsible for yaw along the horizontal plane. Wikipedia. Elevators.

In 1911, a young engineer, a student of Zhukovsky, Boris Yuriev, patented a helicopter with one main rotor, a main rotor swashplate and a tail rotor. With this design, the main rotor is deflected left and right to provide roll or back and forth to lift and descend. And the tail rotor, mounted on the tail, is responsible for heading stability. The swashplate invented by Yuriev is similar to the one that Sikorsky used many years later in America. Did Sikorsky know about Yuriev’s work? Perhaps he knew. Moreover, in 1933, Yuriev lifted the first Soviet helicopter into the sky.

Igor Sikorsky built a snowmobile and carried passengers on it across the frozen Dnieper. Source: Katyshev G.I., Mikheev V.R. Wings of Sikorsky. M., Voenizdat, 1992, behind-the-text illustrations.

Air route. Home

In 1920, in New York, Igor Sikorsky wrote the book “Air Route”. How it was discovered, how it is used now and what can be expected from it in the future” (3) This book was written by a very young man – he was 28 years old. But it was written by a man who experienced a lot, did a lot and lost a lot. These are real memoirs. Who would think of writing memoirs at 28? Only to those who do not see their future and take stock. Thank God, these results turned out to be intermediate.

In this book, Sikorsky described his first acquaintance with ornithopters (macholets), helicopters and airplanes. He talked about how he himself paved the “air route”. By its nature, this is both a popular science book, in which many technical aspects of the construction of airplanes are discussed, and these are pilot stories, sometimes reminiscent of the books of Saint-Exupery.

Sikorsky writes about how he discovered helicopters and how he tried to build them in 1908 and 1910: “The idea of such a device was first encountered more than 400 years ago by Leonardo da Vinci, who in one of his drawings depicted a helicopter with propellers rotating using handles by a person. During the 19th century, many models of helicopters were built, powered by a twisted rubber band, a spring, and even a light steam engine. All of these were small devices, weighing from a small fraction of a pound to several pounds… Here there turns out to be a very serious difficulty: the fact is that in practically a small device you can get much more thrust for each engine horsepower than in a large one. In 1908, I built a small helicopter that weighed no more than ¼ pound, was propelled by a rubber band and flew perfectly.”

In 1910, Sikorsky decided to build a “real helicopter.” That is, at least, such that it will tear its creator off the ground. His helicopter is very similar to Cornu’s. But Sikorsky was unable to lift his apparatus. He gives estimates of the required engine power that is needed to lift the device off the ground, and shows that the power of his device was about 9 pounds. And this is not enough to lift both a car with an engine and a person. That is, in essence, Sikorsky hit the engine power barrier. It was simply not enough for a vertical takeoff, but for a “flat” takeoff, which is how an airplane takes off, this power was already enough.

Sikorsky writes: “…the device lifted its own weight almost completely. Having received a number of interesting scientific data, I stopped these experiments, switched the engine to a light airplane built by that time, and on June 3, 1910, I took off for the first time in it.”

But he never forgot the helicopter. Having listed numerous (and, as it turned out, insurmountable at that time) difficulties, Sikorsky writes: “Does this mean that one should not think about a helicopter in the same way as about an instrument with beating wings – an ornithopter? No way. A helicopter can be implemented, and it would be very useful as an auxiliary device, since it would have one very valuable advantage over an airplane: a properly designed helicopter should be able to take off from any place without a run-up and land on the ground without having enormous speed movements. Thus, a helicopter could take off and land on the roofs of houses inside the city, on the deck of a ship, on the smallest platform, courtyard, etc., while such places are completely inaccessible for an airplane.”

Airplanes first

Igor Sikorsky built his first airplane in 1910 together with engineer Fedor Bylinkin and student Vasily Jordan (Iordan). It was a biplane, which the designers called BIS No. 1 (BJS, in english translation) (Bylinkin, Jordan, Sikorsky). Igor Sikorsky flew on an improved model of BIS No. 2 on June 3, 1910, in the presence of members of the Kyiv Aeronautics Society. Its duration was 12 seconds, height – 1.2 meters, length in a straight line – 182 meters. This was the first successful flight, after which Sikorsky made more than 50 of them, gradually improving the aircraft. It took a year to build a real airplane – S-5

Sikorsky writes: “In the middle of summer, the S-5 was already able to make flights of up to ½ hour lasting, take off from its airfield and walk over the surrounding forests and villages at an altitude of 200-300 meters (100-150 fathoms). Flying at this and higher altitudes requires much less attention and stress than flying low above the ground. Therefore, during such a flight, you can freely look around and admire the unusually beautiful and very special sight that opens from the airplane. It’s clear that this first summer of real flights left an indelible memory.”

This model was no longer inferior to the Wright brothers’ airplanes. Note that the names of almost all the models built by Sikorsky were not particularly diverse (except that the heavy airplanes S-21 and S-22 also had other names “Russian Knight” “Russky Vityaz”, and “Ilya Muromets”): the designer put the first letter of his surname ( “C” – in Russia, or “S” – in America) and model number. The designer got older, and the model numbers gradually increased.

He built his own machines and flew. “Under the airplane there is a huge map, on which in clear weather you can make out the smallest details. Lakes, rivers, even the smallest ones, roads are very sharply and clearly visible; you can easily see streets and even individual houses. All this is clearly visible from a height of 1-2 or even more miles, but individual people are already invisible. It would be natural to expect that from an airplane flying at high altitude one can see very far in all directions. This actually happens, but not always. Usually the air is not clean and transparent enough. You can see quite well what is directly under the apparatus, it is somewhat worse to see obliquely, and further, more than 10-15 versts from the apparatus, the ground completely ceases to be visible and appears for a long distance to be covered with a foggy veil – haze. This is usually the case on a clear sunny day. In fog or rain you can see much less, and very often you can’t see the ground at all. But there are days when the air is exceptionally clean and transparent. Most often this happens at dawn. At such a time, from an airplane flying at an altitude of 2-3 miles, you can see in all directions over a huge distance. I had to make over 1000 flights over Petrograd and its environs and was able to experience such weather more than once. At the same time, it happened that at a flight altitude of 2-3 versts from an airplane it was possible to see at the same time the island of Kotlin, part of the Gulf of Finland, the Neva along its entire length and about a third of Lake Ladoga. Thus it was possible to see 60-70 miles in all directions.”

On the model S-6 Sikorsky reached a speed of 113 km/h. It was this airplane that Sikorsky continued to improve the following year, but now not as a freelance artist, but as an aircraft designer at the Russian-Baltic Wagon Plant, where he was invited by the chairman of the board of directors of the Russo-Ballet, General Mikhail Shidlovsky. He entrusted a very young – 23-year-old engineer – with the most responsible work and did not miscalculate.

Biplane S-6. https://uain.press/uploads/2022/06/Igor-Sikorskij-3.jpg

“Ilya Muromets”

From 1912 to 1918, Sikorsky headed the design bureau of the aviation department of the Russian-Baltic Wagon Plant (German: Russisch-Baltische Waggonfabrik). At this time he was designing a whole series of new aircraft. The “Grand” apparatus (later renamed “Russian Knight”) was built in 1913. The plane had four engines, weighed 4 tons and had a flight speed of 90 km/h. It became the prototype for many passenger and transport aircraft and bombers. The device really amazed its contemporaries: the span of the upper wing was 27 meters, the lower wing was 20 meters, and the wing area was 120 square meters. The pilots were seated in a glass cockpit.

Sikorsky writes: “Most people working in aeronautics at that time believed that a huge airplane would not be able to rise from the ground, that it would be terribly difficult to control, and finally, they pointed out that if one of the engines stopped, the airplane would capsize… I stuck to the other opinions and believed that it was possible to create a large airship and that it would fly better and more reliably than small aircraft. A happy coincidence of circumstances made the construction of the airship possible. The fact is that at that time, at the head of the Russian-Baltic Wagon Plant, where small airplanes of my system were built, there was a man of outstanding intelligence and determination – Mikhail Vladimirovich Shidlovsky. As a former naval officer who had circumnavigated the world, he clearly understood how reliable navigation in the ocean of air could be achieved. When in the summer of 1912 I introduced him to the calculations and drawings of a large airplane with four engines, with an enclosed spacious cabin, M.V. Shidlovsky wished that the construction of such an airship be immediately started at the Russian-Baltic Plant. That same evening, August 17, 1912, the laying of this airplane took place. While it was being built, many were distrustful of the fact that this large, heavy machine could take off. The airplane was completed and assembled on the field in the spring of 1913. Several runs in a straight line, during which the airplane slightly separated from the ground, showed that everything was fine. Finally, on May 13th, it was decided to try to get into the air for real. It is clear that I myself fit behind the wheel of my airship.”

And the huge machine took off. But that was only the beginning.

The four-engine S-22 Ilya Muromets was designed and built at the same time. The first prototype was laid down in August 1913, and on December 10 (23), 1913, it first took off from the ground. Test flights have begun.

Sikorsky writes: “The new ship, named “Ilya Muromets”, was completed in January 1914. It was even bigger than “Russian Knight” (Russky Vityaz). Its wings had a span of about 15 fathoms (about 31 meters), their surface was over 300 square arshin(yard) (over 150 sq.m). The ship with its cargo weighed about 300 poods (5 tons). It was driven, like the “Russian Knight”, by 4 Argus motors of 100 hp each. strength everyone.”

But what Sikorsky writes about with particular pride is the amenities for passengers of the Ilya Muromets.

Flights usually took place in open cars. And when Sikorsky first took the Russian Knight into the air, which had a closed cockpit, even at the first moment he was confused: there was no wind in his face and there was no usual feeling of speed, he had to navigate only by instruments. But they quickly get used to the comfort.

Sikorsky writes about unprecedented amenities on the board of “Ilya Muromets”.

“In the large body of this apparatus there were several comfortable and spacious cabins. At the front was the helmsman’s (pilot’s) room, then there was a living room, then a small corridor and a bedroom. The door to the restroom also opened from the corridor. All cabins had windows through which you could look out during the flight. The ceiling in the cabins was so high that one could stand without bending over. They were warm because heating was installed. For this purpose, part of the hot exhaust gases from the engines was passed through a pipe that ran below the wall along the cabins. The hot pipe heated the rooms sufficiently. Just in case, the ship had two external balconies that could be accessed during the flight. One of them was located on the building above the place where there was a corridor and a restroom. This balcony could be reached by stairs from the corridor.”

The mention of a balcony seems completely unexpected to a modern person. But the maximum speed of the airplane was 100-130 km/h, and the cruising speed was even less. And the height is small – 2-3 kilometers. So it was quite possible to go out onto the balcony. The breeze, of course, is not weak, but it will not blow away.

“In February 1914, this aircraft set a world record for flight with the largest cargo and the largest number of passengers. The ship easily took off and walked over the outskirts of Petrograd for half an hour, carrying 16 people and one four-legged passenger, “Shkalik,” who was everyone’s favorite at the airfield. During this flight, the ship lifted about 80 poods into the air.”

In the spring of 1914, the first copy of the Ilya Muromets was converted into a seaplane with more powerful engines. In this modification, it was accepted by the naval department and remained the largest seaplane until 1917. Sikorsky did not yet know that it was seaplanes that would bring him his first fame in America 15 years later.

Ilya Muromets lands at the airfield. Wikipedia

The first long-distance flight of Ilya Muromets was scheduled for June. It was decided to fly to Kyiv with refueling in Orsha. Sikorsky writes: “The distance from Petrograd to Kyiv by rail is about 1300 versts. The fastest trains passed it in 26 hours.” This is not to say that the flight went completely smoothly.

Before Orsha everything was fine. We sat down, refueled, but the weather turned bad. And it began… “At low altitude we flew across the Dnieper and then, just above the buildings, we flew over the outskirts of Orsha. Only once you were above the free field could you make a circle and gain a little height. But here the condition of the air very soon made itself felt. About 2 minutes after the start of the flight, when there were some 75 fathoms altitude, the ship suddenly tilted sharply and then threw down 25 fathoms. When the ship leveled out and managed to rise a little higher again, approximately the same thing happened again. In addition to such large ones, many small movements and rocking of the ship in all directions, up and down, were also felt. It was very difficult to manage. However, the flight continued, because it was clear that it would be calmer at high altitude. I was driving the whole time. About 15 minutes after the start of the flight, a mechanic suddenly ran up to me and began pointing to the nearest left engine. You could immediately guess from the mechanic’s face that something was wrong. Taking a closer look at the engine, it was not difficult to see the reason for the mechanic’s concern. It turned out that the copper tube carrying gasoline from the tank to the engine had burst, and gasoline was pouring in a wide stream onto the wing. All this lasted a few seconds. The engine quickly used up what was in its carburetor and stopped, and from the last flash the fire spread to gasoline, which poured onto the wing. Thus, a fire arose behind the stopped engine, which immediately assumed quite impressive proportions. Lieutenant Lavrov and the mechanic quickly climbed onto the wing with fire extinguishers and began to extinguish it. With their combined efforts, the fire was eventually extinguished, although not without difficulty, especially since the sharp pitching made it very difficult to work outside on the wing. Although the ship was kept in the air on three engines, it was decided to go down to the ground to make the necessary repairs and, most importantly, check the parts that could have been damaged by the fire.”

The scene of extinguishing the engine looks completely Hollywood, but pilots with fire extinguishers on the wing of a flying airplane are the reality of the world in which people were just learning to fly. We managed to land the airplane. The gas line was sealed and refueled. And we flew to Kyiv without any special incidents.

Today, when we grumble about the inconveniences of a flight, saying that the seats are uncomfortable, the food is tasteless, the air is dry, it is sometimes worth remembering those people who fell ill with the sky at the beginning of the 20th century. They rose higher and higher. They used to fall, break their arms and legs, and die. And if they survived, they took their actually very unreliable machines into the sky again. They paved our air routes along which we glide so easily and carefree today.

The First World War began. The Ilya Murovtsy continued to be built at the Russian-Baltic Plant. Now they were bombers. In total, about 60 vehicles were built. It was the world’s first true bomber aircraft. The squadron flew 400 sorties and dropped 65 tons of bombs.

But the revolution began. Work at the Russian-Baltic Plant was stopped. Igor Sikorsky’s son Sergei described his father’s escape from Russia: “Igor Ivanovich left Russia because that he was in danger of being shot. At the beginning of 1918, one of his former employees, who worked for the Bolsheviks, came to his home at night and said: “The situation is very dangerous. I saw the order for your execution.” This was the time of the Red Terror, when people were shot on the spot, without trial. And Sikorsky represented a double danger for the communists: as a friend of the Tsar and as a very popular person. All of Petrograd knew him, many looked at him as a hero. The Tsar himself, Nicholas II, came to the airfield in Tsarskoe Selo to see how the young Russian pilot flies. Having received a warning about the danger, Igor Ivanovich went to Murmansk. From there, on a small English steamer, he went to Liverpool, then to Paris. The French received him very well and immediately offered him a contract. The talk was about designing a new, even more powerful Muromets. My father worked on this project for almost the entire year. But in November 1918, the war ended and the French government stopped funding military orders. My father lived in Paris for several more months. And then, at the beginning of 1919, he emigrated to America.”

America

On March 30, 1919, Sikorsky sailed to New York on the ocean liner Lorraine. The thirty-year-old engineer initially survived thanks to private lessons. But Sikorsky, together with a group of enthusiasts, continued to work on airplanes. They believed in him, and he believed in them.

On March 5, 1923, Sikorsky founded his own aviation company, Sikorsky Aero Engineering Corporation. Sikorsky himself became the president of the company, but the post of vice-president was taken by the great composer and pianist Sergei Rachmaninoff. It was Rachmaninoff who invested the initial capital of $5,000 in this business.

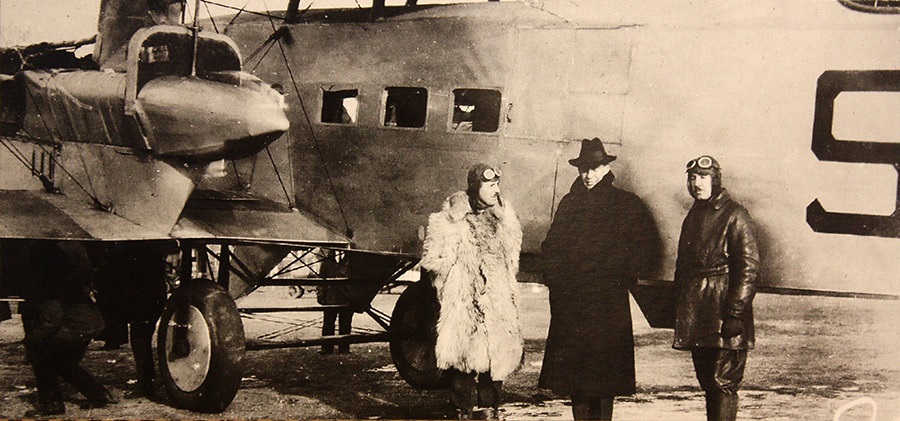

Rachmaninoff (in the center) and Sikorsky (to his right) at the S-29 transport aircraft. Source: Katyshev G.I., Mikheev V.R. Wings of Sikorsky. M., Voenizdat, 1992, behind-the-text illustrations.

On May 3, 1924, the twin-engine S-29A biplane took off into the sky with twenty happy company employees on board. In 1927, the aircraft was sold to the famous pilot and businessman Roscoe Turner, who carried out charter flights throughout the country. Over time, he resold this car to one of the Hollywood film studios, where he was filmed in a film about the air battles of the First World War.

In 1926, Sikorsky first tried to conquer the Atlantic. But the S-35 plane, specially created for the flight New York – Paris, met with a disaster; the pilot and mechanic were saved by a miracle. The surviving pilot of the plane, Rene Fonck, instead of cursing the aircraft manufacturer, found the money to finance a new plane. He, unlike the newspapermen who attacked Sikorsky, understood how good this machine was, and knew that the incident that almost cost him his life was an accident. But Fonck never became the first pilot to cross the Atlantic: Charles Lindbergh preceded him in 1927.

In 1928, Sikorsky began building seaplanes. He produces the S-38 model, which is unconditionally recognized as the best in its class. The small enterprise received orders from the US Department of Defense and Pan America, from Canada and South America, from Europe, several planes even ended up in the Soviet Union (one of them is shown in the film “Volga-Volga”). Sikorsky builds a new large plant in Bridgeport, increases staff, organizes exemplary production, but the Great Depression ruins all plans.

Orders are melting away, already built aircraft are not being sold. But Sikorsky finds a way out: he negotiates the sale of his company (at that moment it was called Sikorsky Aviation) to United Aircraft.

‘Pan America’ becomes Sikorsky’s customer. He builds new models and sets record after record: in flight range, in weight moved, in speed (his planes reach speeds of more than 300 km/h). His S-42 Clipper, built in 1934, flies from America to New Zealand. This is a worldwide success.

Passengers take their seats in the S-40.

https://habr.com/ru/companies/macloud/articles/564846/

Mr. Helicopter

The idea of creating a helicopter, the model of which Sikorsky assembled as a young man in 1908, never left him. But in the late 30s he was already a completely different person – an experienced entrepreneur, engineer and pilot. And a completely different state of technology, primarily engines. Now Sikorsky no longer had a problem getting the helicopter into the air: there was more than enough power for a vertical takeoff.

Now the problem was different – in the maneuver. Sikorsky chooses a simple single-rotor design with a swashplate. In it, the main rotor is responsible for all the maneuvers of the helicopter – it just needs to be tilted correctly either to the sides or back and forth. And to prevent the helicopter from spinning, it is stabilized by a propeller on the tail.

But Sikorsky’s first development, called VS-300, “had been learning to fly” for several years.

The first model of a Sikorsky helicopter (with the inventor at the controls) takes off from the ground. Of course, he is not wearing a helmet, but a hat. Source: Katyshev G.I., Mikheev V.R. Wings of Sikorsky. M., Voenizdat, 1992, behind-the-text illustrations.

The model flew perfectly backwards and sideways and did not want to move forward. Sikorsky redesigned his helicopter 18 times in just a year. And the helicopter took off.

The first helicopter, which went down in history as XR-4 (this was the code name for the model in the military, in “civilian” language – VS-316), took off in mid-January 1942. The military tested it on their own and were quite pleased with the result.

130 of these helicopters were produced, which took part in both military and rescue operations during the war. Helicopters (of the next generation) were ordered by the armies of Britain and Canada. But not only the armies needed a helicopter: the next Sikorsky model – the S-51 – was purchased by civilian departments, rescuers and the post office. Sikorsky’s success was the development of the S-55 helicopter, which was produced for more than 12 years not only in the USA, but also under license in the UK, France and Japan.

Helicopter S-56. https://habr.com/ru/companies/macloud/articles/564846/

The S-61 became the first helicopter to fly across the Atlantic in 1967, and in 1970 the S-67 flew across the Pacific with additional fuel tanks. But this was done by employees of Sikorsky’s company, including his son, and not by himself.

Planet of People

In America, Igor Sikorsky married for the second time. His first family remained in Russia. He married Elizabeth Semion in 1924 in New York. They had four sons: Sergei, Nikolai, Igor and Georgiy. Their daughter from her first marriage, Tatyana, also lived with them for some time.

Sikorsky’s wife is Elizabeth and four sons. Source: Katyshev G.I., Mikheev V.R. Wings of Sikorsky. M., Voenizdat, 1992, behind-the-text illustrations.

Igor Sikorsky was engaged in educational activities and actively participated in the work of emigrant organizations in America. In a certain sense, Sikorsky felt responsible not only for his family, company or even country, but also for humanity. Being a sincerely religious person, he wrote several theological works. But even there, Sikorsky returns to the most important image for him – the airplane. Only this is no longer a heavier-than-air aircraft, rising high on the ground, but the Earth itself and its people. And people lack the main thing – faith in God.

In the work “The Invisible Encounter”, completed in 1947, when the wounds of the war that had just passed were so painful, Sikorsky will write: “However, it can be stated definitely that mankind being controlled and directed by spiritually unconscious or dead men would be in the position of a rushing airliner with an unconscious or dead crew in the control cabin. Such leadership cannot create reasonable and stable forms for the existence of a human society. All higher conceptions, which are of definitely spiritual origin, such as love, truth, honor, freedom and compassion, would inevitably lose all binding power, all living reality. They would remain only as dead empty shells in the stockroom of collective memory.”

And further: “ I want to stress again that no matter how tempting and promising, or how well supported by theories and statistics, all new political, economic and social arrangements of the world are only the creation of human intellect, just as aircraft or radio. An efficient airplane can render more beneficial services to mankind or it can spread more dreadful destruction. A perfected radio can broadcast more clearly good will and enlightenment, or it can spread more effectively pernicious lies and hate.”

Sikorsky was the man who built the world’s first bomber aircraft, he worked for the war – both for the army of the Russian Empire and for the Pentagon – his planes and helicopters not only helped people get closer, not only saved, but it wasn’t heavenly manna they dropped on the ground. And he understood this well.

In the early 60s, Sikorsky retired. Although he was still full of energy and work in his company was in full swing. New helicopters were launched, new records were set: range, speed, payload. The company flourished. His son, Sergei, was already working there. But Sikorsky decided to finish.

He died on October 26, 1972. Igor Ivanovich Sikorsky is buried in the Saint John the Baptist Russian Orthodox Cemetery in Stratford, Connecticut, where the Orthodox St. Nicholas Church was built at his expense.

Author of the text: VLADIMIR GUBAILOVSKY

(1) Tager A. S. Tsarist Russia and the Beilis case. M., OGIZ, 1934.

(2) Katyshev G.I., Mikheev V.R. Wings of Sikorsky. M., Voenizdat, 1992

(3) All quotes from Igor Sikorsky are given according to the publication: Air Route. How it was discovered, how it is currently used and what can be expected from it in the future. M.: Russian Way, 1998. http://militera.lib.ru/research/sikorsky/index.html< /a>.

Vladimir Gubailovskii 14.02.2024